Stations

Railways require an enormous and varied infrastructure to operate. For many passengers, the stations were often the most familiar elements of that infrastructure. From the many platforms of Flinders Street Station to the humble corrugated iron waiting shed of a Mallee branchline and the enigmatic timber signal box, all were essential parts of Victoria's comprehensive rail network.

Station designs varied according to architectural styles of the era, their location and government priorities. Some included elaborate tearooms, a grand clock-tower or adjoining stationmaster's residence. Others were little more than a rain shelter devoid of staff or comfort. Most stations featured at least one siding or a small goods shed, and some included loco depots, signal boxes and extensive rail yards.

City terminals

Three major city terminals have acted as the hub of Victoria's passenger and freight train services over the past 150 years.

Melbourne's main passenger station, Flinders Street, is built on the site of Victoria's first station - the city terminus of the Hobsons Bay Railway Company's line to Port Melbourne (previously Sandridge). The humble building which serviced passengers and freight in 1854 was progressively extended over the next half a century to become a motley collection of ticket offices, footbridges and platforms with various awnings by the turn of the century. Between 1900 and 1910 the station was entirely rebuilt creating the grand facade which remains today. The impressive clocktower and imposing main entrance with its large dome roof and row of destinations clocks quickly began a key Melbourne landmark. By the 1930s, Flinders Street could lay claim to being the world's busiest station serving almost 300,000 passengers daily.

Princes Bridge Station, situated on the eastern side of Swanston Street, originally opened in 1859 as the terminus of the Melbourne & Suburban Railway Company's lines to Hawthorn and Windsor. It was first linked with to Flinders Street Station by a tunnel under Swanston Street in 1865. It was then closed for a period before becoming the terminus of the government's Gippsland line in 1879 and of the Hurstbridge and Northcote lines in 1901. Princes Bridge Station lost its separate identity in 1980 when its platforms were integrated into Flinders Street Station and the suburban lines it served were diverted to connect directly to the new underground loop.

Far more humble in its origins was Spencer Street Station, the first government railway terminus. Originally known as Batman's Hill Station, it opened for passenger traffic in 1859 with a single passenger platform and a temporary timber station building. As the government railway network extended to the north and west of Melbourne, Spencer Street became a major freight hub with extensive goods yards and several large goods sheds, but its passenger facilities remained a poor cousin of the grander country stations. In the 1920s, the existing outer suburban platforms were built with a connecting subway, but the main booking hall remained little more than a large corrugated-iron roofed shed. Spencer Street finally gained a modern passenger hall and refreshment area when the No.1 platform was rebuilt for the opening of the Sydney-Melbourne standard gauge link in 1962.

Flinders Street and Spencer Street Stations were first linked by a street-level 'tramway' in 1879, but its use was restricted to overnight goods trains to prevent interruptions to road traffic. The first section of the overhead viaduct linking the two stations was completed in 1891, being duplicated for the suburban electrification in 1913-15 and again for the underground city loop in 1981.

Flinders Street Station

Princes Bridge Station

Spencer Street Station

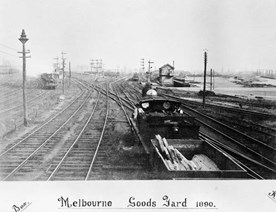

Melbourne Goods Sheds

Suburban stations

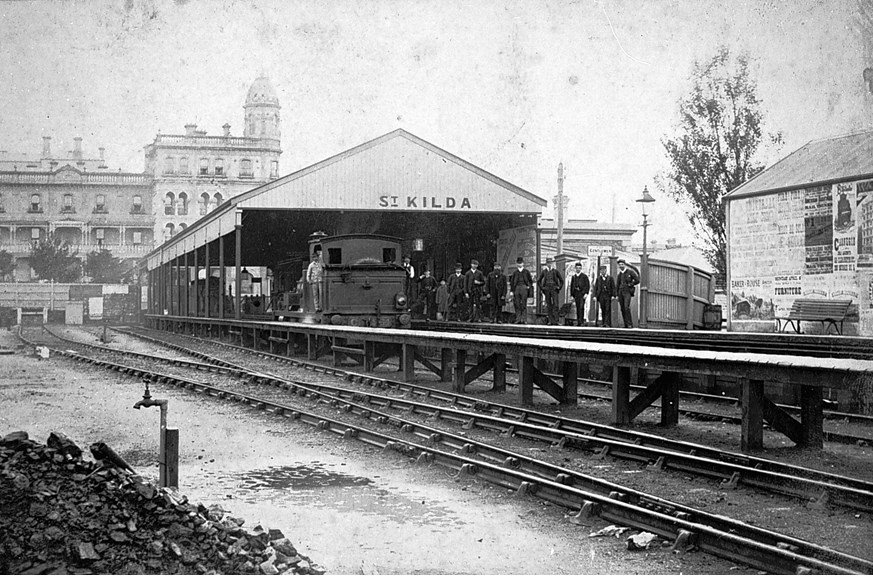

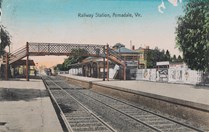

The early suburban stations built by the private railway companies were typically temporary, insubstantial structures, with the result that only two - St Kilda and South Yarra - retain any of their original fabric today. Built in 1857, St Kilda Station is Victoria's oldest substantially intact suburban station building, though it is no longer operational and has been redeveloped as a commercial precinct since the St Kilda line was converted to light rail operation in 1987.

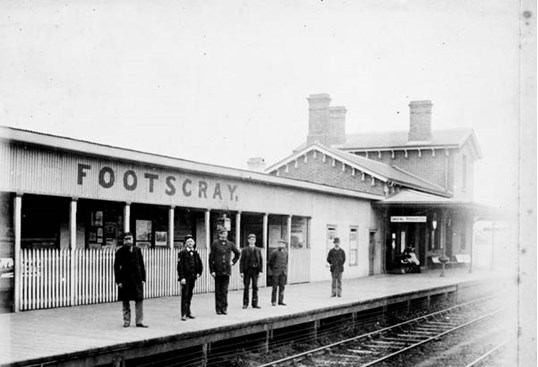

Most of Melbourne's older suburban station buildings were built during the 1880s, reflecting the rapid expansion of the suburban system that occurred during the 'Octopus Acts' era. The generic form of these stations reflects the standard designs from which they were built. They were predominately constructed from brick with slate or later terracotta tile roofs and incorporated the lessons learnt from earlier country stations, such as the provision of a cantilever veranda to protect passengers from the Australian weather.

Generally suburban stations followed a standard layout with a more substantial building containing the booking hall, ticket office, waiting room and rest rooms on the up-side platform (where trains travelling to the city pulled in), while a smaller ticket office and passenger shelter with perhaps a parcel office or storeroom where situated on the opposite down-side platform. At many of the busier stations an overhead footbridge (or later a subway) was provided to allow passengers to safely cross the tracks between the platforms.

During the early twentieth century many suburban stations handled a substantial parcel and goods trade in addition to passengers, while some had sidings serving local factories or warehouses.

Brighton Beach Line

Eastern Suburbs Line

Essendon and Broadmeadows Line

Footscray Station

Hawthorn Station

Richmond Station

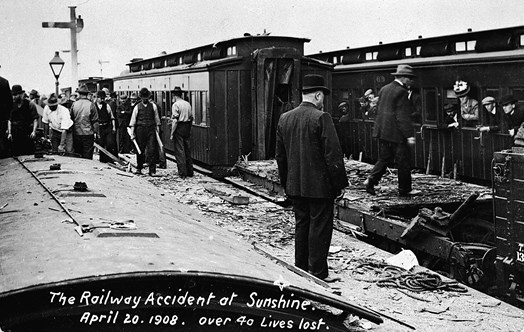

Sunshine Station

Suburban station yards

Country main line stations

Main line stations included a variety of railway buildings serving major towns, railway junctions and intermediate stopping points on the major rail routes radiating out of Melbourne.

On both the first government main lines to Ballarat and Bendigo the earliest stations were solid bluestone structures built to a standard design reflecting the typical English country railway style with booking office and passenger waiting rooms in a single storey building and adjoining two storey stationmaster's residence. These compact, well-crafted structures were built with a view to longevity, with many still standing decades after the final closure of the working stations. Early stations were built without verandahs, with most having simple timber-posted verandahs protecting the platform side added in later decades. In contrast to the standard station designs were the one-off buildings designed for major early railway hubs, of which Ballarat was undoubtedly the grandest with the arch of its large engine hall spanning the tracks between the two platforms. Geelong and Bendigo were also important early individual designs.

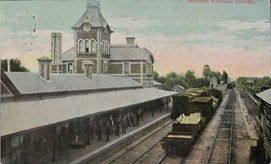

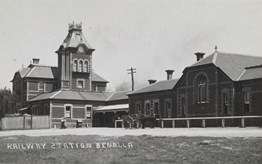

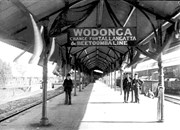

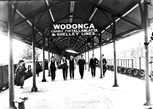

The rapid expansion of the trunk routes during the 1870s and 1880s, prompted a more modest approach to station architecture with a range of new standard designs being developed most of which were single storied structures built in red brick, with simpler sandstone or polychrome brick detailing. Designs began to more closely reflect the Australian climate including wide cast-iron posted platform verandas amongst other standard features. Standing apart from the standard designs of the boom period were the grand station buildings built at some of the major regional towns such as Maryborough, Benalla and Seymour and at the border crossing points of Wodonga and Serviceton, where additional facilities such as refreshment rooms were provided.

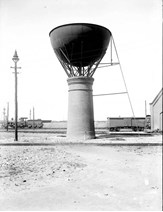

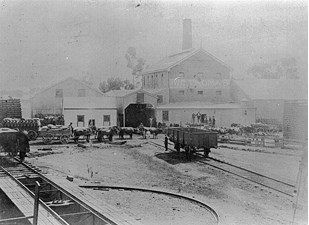

Other typical features of main line stations included substantial brick goods sheds, locomotive depots, water tanks, engine turntables, shunting sidings and the ubiquitous timber signal box where train movements through the station yard and adjacent railway junctions were controlled.

Built in bluestone

Built in brick

Built in timber

Ballarat Station

Benalla Station

Bendigo Station

Echuca Station

Geelong Station

Maryborough Station

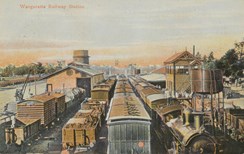

Wangaratta Station

Wodonga Station

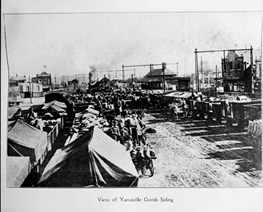

Goods sheds and station yards

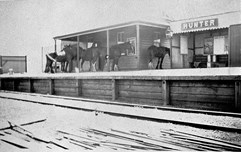

Country branch line stations

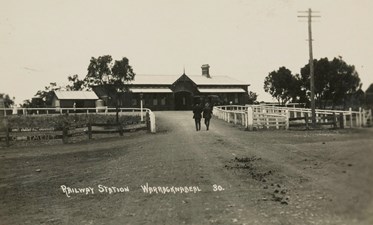

Given the smaller volume of traffic handled by country branchline stations they were generally of more modest design than mainline stations. Compared to the busy tearooms and whizzing of parcel trolleys of metropolitan and mainline stations, waiting for the train at a branchline station could be a rather monotonous experience.

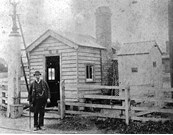

The first branchline stations had their origins in the 'light lines' era of the 1870s - a period during which economy was of greater concern to the railways than grandeur. Simple brick or timber buildings built to a variety of standard designs were generally favoured, though from the 1920s many minor branchline stations and stopping places were given little more than a crude corrugated-iron clad passenger shelter.

Most country branchline stations followed a similar layout with a single passenger platform on which there was a main building housing the ticket office, stationmaster's office, waiting room and ladies 'restrooms' or toilets, while men's toilets were housed in a separate unroofed corrugated-iron structure. A separate lamp store was often built at a distance from the main building because of the risk of fire from the flammable kerosene fuel. On the opposite side of the station yard there was typically a corrugated iron goods shed with its own short platform and occasionally a hand crane for assisting with heavier loads.

Most branchlines stations that were staffed featured at least a small office where clerical duties could be performed and where shift workers might grab a few hours rest lying directly on the floor. Because engine drivers often had to performing shunting duties at intermediate stops on branchlines, trains could often run hours behind schedule but staff were still expected to be on duty. Some smaller stations remained unstaffed in later years, with the guard on the train or a traveling staff member from a larger station on the same line being expected to alight at the stop and process any passengers or goods.

Built in brick

Built in timber

Corrugated iron

Goods sheds

Station yards

Cressy Station

Timboon Station

Warracknabeal Station

Loco depots and engine sheds

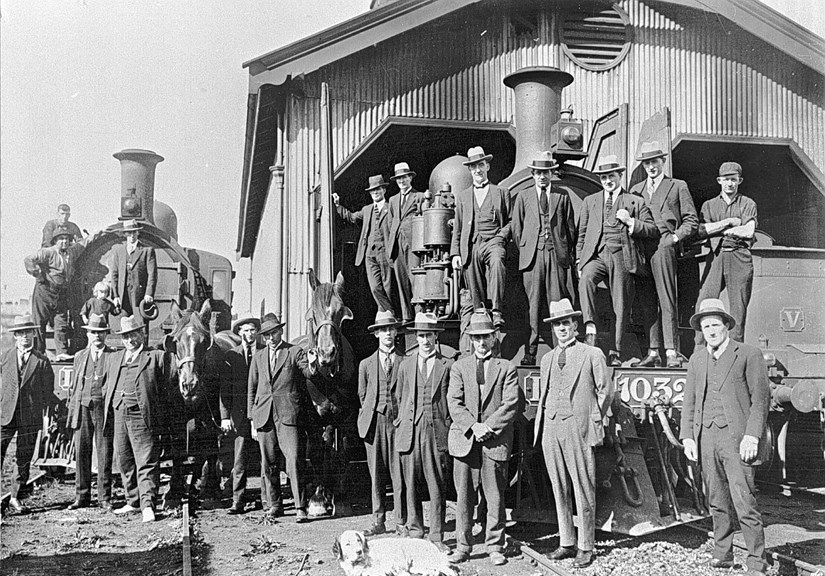

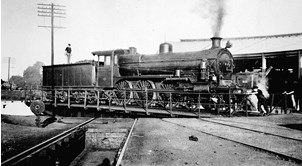

Loco depots and engine sheds were an essential part of the Victorian Railway system throughout the steam age. They provided an undercover space where steam locomotives could be prepared for use and where routine inspections or repairs could be undertaken. Activities typically carried out in loco depots on a daily basis included washing out boilers, oiling and cleaning, replenishing coal and water, making minor adjustments to running gear and lighting up for steam raising at the beginning of each day.

When the first country lines where built to Bendigo and Ballarat substantial brick or bluestone engine sheds were erected at most of the major stations, but the main loco depot at Spencer Street was little more than a large corrugated-iron shed. The main loco depot serving the Melbourne & Hobsons Bay United Company's suburban lines was built at Port Melbourne.

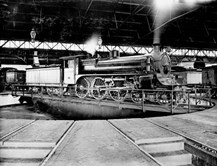

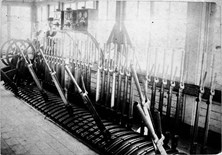

With the rapid expansion of the Victorian Railways system in the 1880s, a decision was made to locomotive operations with as many crews as possible being based at larger central depots. In 1888, a large new depot was built at North Melbourne that became the biggest in Victoria with three 70-ft turntables each with 25 radiating engine bays or 'roads' housed in a large rectangular brick building. Large new rectangular engine sheds enclosing two turntables were also erected at Bendigo and East Ballarat in 1888-9.

Other major loco depots were located at major junction stations such as Ararat, Geelong, Maryborough, Seymour and Traralgon. These depots typically took the form of a roundhouse built as a circular corrugated-iron clad shed covering the outer end of bays radiating from a central open turntable. The Geelong Depot built in 1916, was the only full roundhouse in the State, with 36 engine bays radiating around a central 70-foot turntable. Other roundhouses covered only part of a circular arc.

At smaller country stations and branchline termini, loco depots typically took the form of a simple rectangular corrugated-iron clad building with one or two engine bays side-by-side.

In July 1962 a new modern loco depot was built at South Dynon to service and maintain the State's fleet of diesel and mainline electric locomotives. Unlike steam engines, diesel locomotives did not require constant daily maintenance or stabling overnight. Many former loco depots fell into disuse or were dismantled.

At North Melbourne, the old loco depot affectionately known by steam men as 'the big smoke' was demolished on 20 January 1965 with assistance from steam locomotive K-188.

Water tanks

Signals and safe-working

Effective signalling has always been an essential part of safe-working practises on any public railway.

When railways first began in Victoria in the 1850s, the first signals took the form of tall semaphore poles with two signal arms operated by a lever from the base of the pole. The semaphore arms worked through the lower left quadrant being positioned at 90 degrees to indicate 'stop' and at 45 degrees for 'caution', with the arms disappearing entirely behind the mast when it was all clear to 'proceed'. At night a rotating lamp was used, showing a red light for 'stop', green for 'caution' and white for 'proceed'.

When the first 'interlocking' signal gear was installed from 1876, a new type of semaphore signal came into use that was connected by a wire to a remote signal frame with levers for operating both the signals and points. The new signals arms were painted red with a white vertical stripe and also worked in the lower left quadrant. They also had a 'spectable' frame with coloured glass on the inner end which moved with the arm to show either a red or green light at night. Later an improved version was developed: known as 'tumble arm' signals because they pivoted near the outer end.

With the spread in use of interlocking signals during the 1880s and 1890s, separate signal boxes began to appear at many suburban and country stations. These offered signalmen a high vantage point from where all signals and points throughout a station yard could be controlled by single blank of levers. A complex system of rods and wire cables ran beside the tracks throughout the station yard to control the various points and signals, which were 'interlocked' so that no signal could be changed without the corresponding points first being set.

On single-track country lines 'staff and ticket' systems or electrically interconnected 'electric staff' machines were in use by the early 1900s to ensure that only one train at a time had the authority to proceed into a given section of track. Crossing loops were provided for trains to safely pass in opposite directions at the end of each section.

By the late 19th century, busier level crossings were protected by hand operated gates or interlocking gates controlled from the signal box, but such systems were not automated and required a gate keeper or signalman to be on hand at all times trains were running. In 1923, safety at unmanned level crossings was improved with the installation of the first automatic 'wig-wag' signals which used a swinging overhead arm to warn drivers on the road of an approaching train. Flashing automatic lights and bells at level crossings were used from 1933, but it was not until 1956 that the first automatic boom gates in Victoria were installed on Toorak Road, Tooronga.

Signalling

Signal boxes

Level crossings

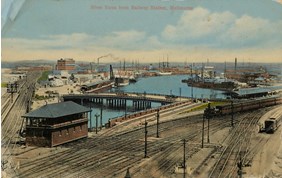

Ports and piers

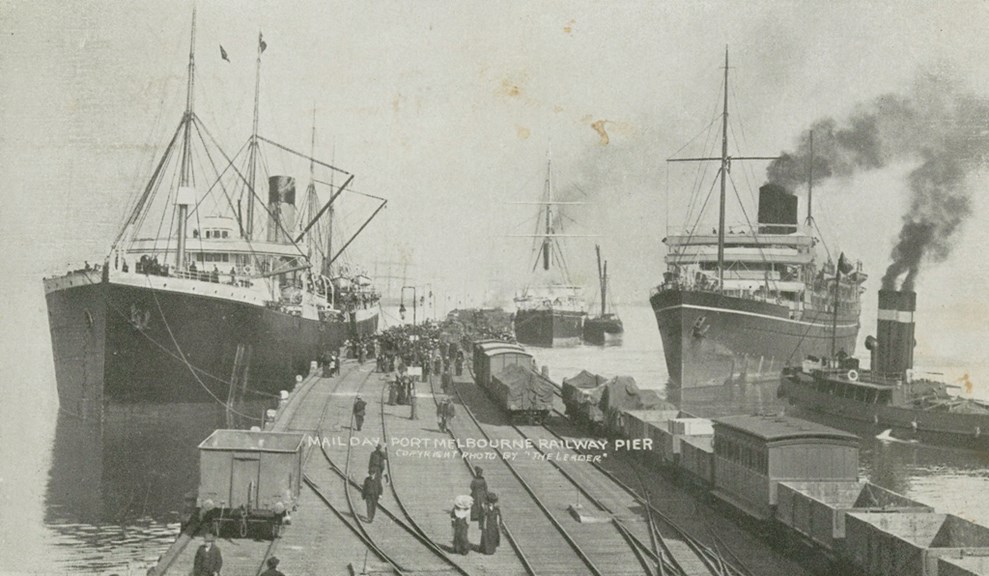

There has been an association between piers and railways in Victoria since 1854 when Australia's first steam-powered railway began operating between central Melbourne and Railway Pier at Sandridge (later Port Melbourne) on the eastern shore of Hobsons Bay. Ports and piers have historically been the interface between two of the most important forms of transport in Victoria.

The role of Railway Pier at Port Melbourne as a major shipping terminus for both passengers and freight continued until the 1920s when it was rebuilt as Station Pier. After the Second World War, Station Pier welcomed hundreds of thousands of immigrants to Australia, remaining Victoria's major international passenger shipping terminal until the end of age of mass ocean travel in the 1970s. The train trip to or from Port Melbourne was for many people the first or last journey they would make in Australia. Whether heading to Ballarat's goldfields in the 1850s, or to the postwar migrant camp at Bonegilla in the 1950s, getting on or off a train at Port Melbourne was part of the journey.

At Williamstown, on the western shore of Hobsons Bay, another railway pier was built by the Melbourne, Mount Alexander & Murray River Railway Co in 1854. It became the first pier connected to the government railway system and was used as the landing point for locomotives, rollingstock and construction materials required to build the first inland railways. As the rail lines extended to the west and north of Melbourne, Williamstown became the major export point for much of Victoria's wheat harvest and other farm produce.

When the Bendigo railway was extended to Echuca, in 1864, a direct rail connection to the river port was made. The railway enabled Victoria to tap into the booming paddlesteamer trade on the Murray-Darling River system with Echuca becoming for a period Victoria's second busiest port.

As railways were extended beyond Ballarat and Colac into western Victoria in the 1870s, Geelong became another key railway port, handling much of Victoria's export wool trade in addition to wheat, timber and other produce.

Over the next two decades, piers and wharves at Portland, Warrnambool, Port Fairy, Port Albert, Sale and Bairnsdale were all connected to Victoria's Railway system. Gaining a railway connection could be a mixed blessing for regional coastal ports. On the one hand it provided a means of conveniently moving produce from the hinterland to the port for export, but the Railways Department then began to offer discount freight rates from regional ports to Melbourne, fearing competition from the coastal shipping trade.