A New Industrial Era

The Abbotsford Factory, 1884–1964

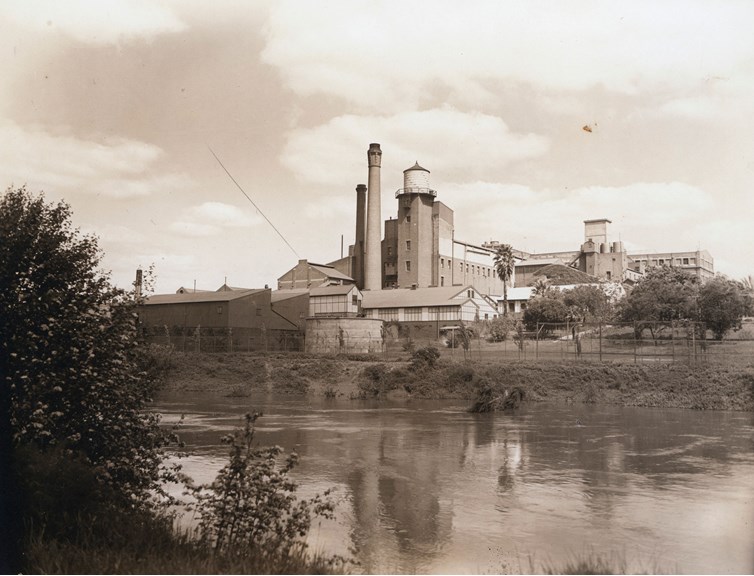

On the banks of the Yarra River, home to the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people for many thousands of years, a new industrial era was emerging in Abbotsford, Melbourne, in the late 1880s - in the form of a factory to make photographic products.

…Its aim is to produce more and more Australian goods for Australian photographersAustralasian Photo-Review, 15 January 1915, p.49

The Eastman Dry Plate Company, later known as the Eastman Kodak Company, was founded in America in 1881, and during the late 1800s was having a significant impact worldwide as it popularised the use of cameras, film and paper for everyday photographers.

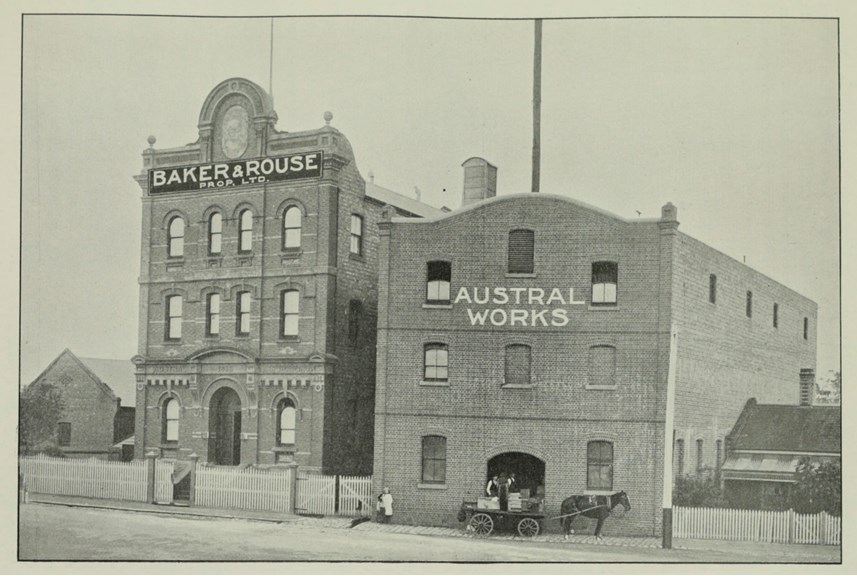

In 1905 Kodak began to have an influence on the Baker & Rouse business. Firstly Baker & Rouse became the sole agents for Eastman Kodak and their allied companies. This was a profitable direction for the company, that no doubt had follow on effects on the factory at Abbotsford.

The most significant change, however, occurred in 1908 when Baker & Rouse Pty Ltd merged with Eastman Kodak to become Australian Kodak Limited.

The new Australian company was given access to the closely guarded formulas for a wide range of Kodak products, so that they could start producing and manufacturing these products locally. These were made alongside the very successful Baker & Rouse ‘Austral’ branded products.

Most importantly, as part of the new company arrangement, Eastman Kodak invested considerable funds into the existing Baker & Rouse factory, now known as the Austral-Kodak Works. Around £60,000 were spent in the first two years, in order to construct new buildings and install manufacturing equipment.

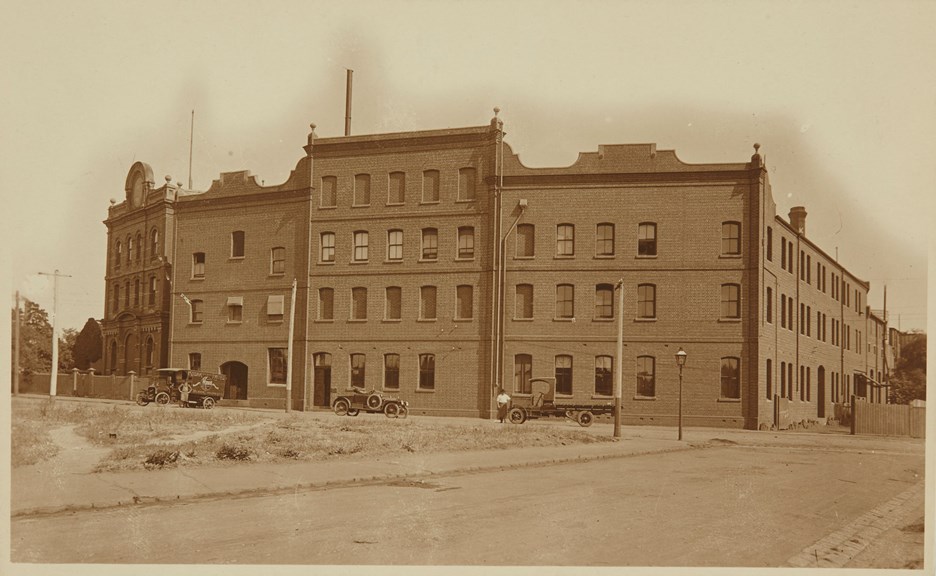

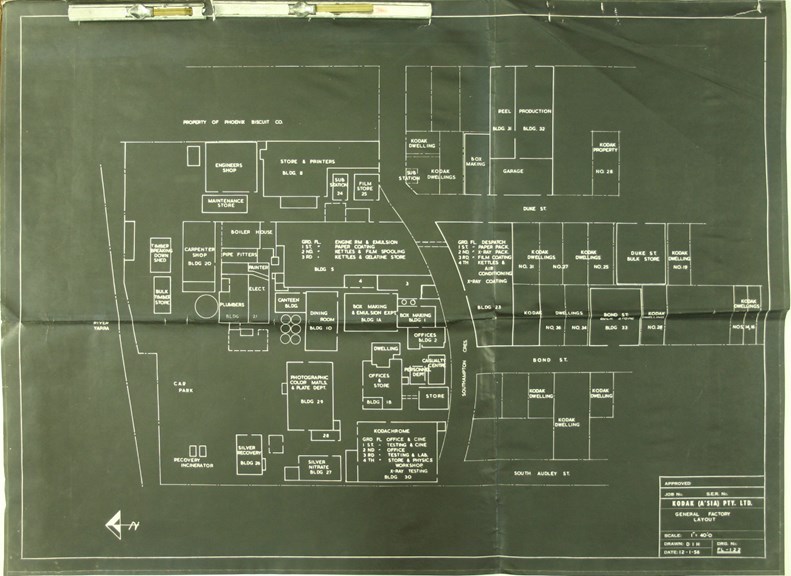

By 1909 there were four multi-storey buildings fronting the north side of Southampton Crescent, as well as other buildings behind them on the river side of the site. The 50 HP steam plant installed in 1897 was replaced around this time by boilers of 300 HP, which drove electric generators of 150 HP.

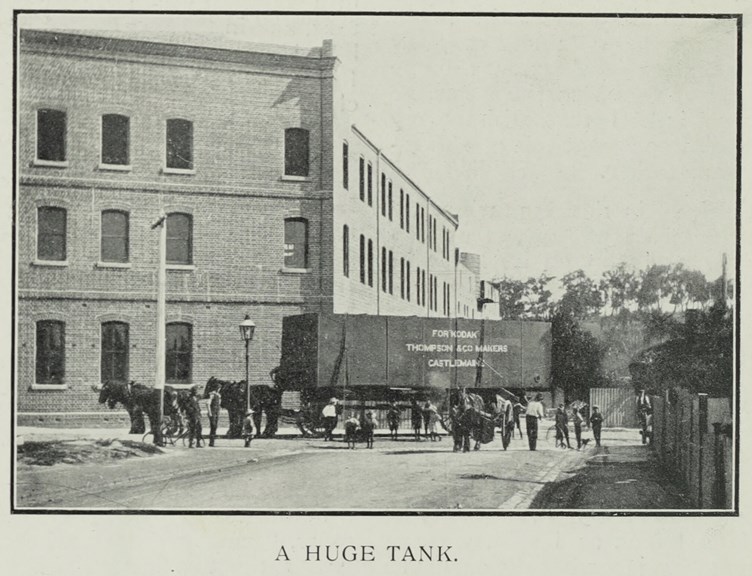

In 1909 Australian Kodak Limited hauled a huge 11 tonne iron tank that could hold 20,000 gallons of liquid – from Thompson & Co in Castlemaine – and installed it in the factory. It was 30 feet long, 10 feet high and 8 feet deep.

It was reportedly either used to hold purified water or to hold chilled brine which was pumped around the factory to provide chilled air or water.

In January 1915 the Kodak factory at Abbotsford was described as having a total floor area of about 2.5 acres with £100,000 worth of building and plant. The buildings were protected from fire by a modern sprinkler system, which was surely reassuring to the company, considering the huge financial investment in the site.

The modern factory was run by steam generated electric power with its own switchboard to distribute the power and had 1500 electric lights connected.

The tall chimney of the Powerhouse located at the back of the factory was visible to all as a beacon of industrial success. The various buildings across the site were also conveniently connected by a telephone system and there was a forty clock magneto control system with employee clock-in cards.

The factory was supplied with refrigeration by a steam driven machine that could make 75 tonnes of ice in 24 hours. The air was filtered, because “dust was the enemy”, and the temperature and humidity was maintained for ideal production conditions.

It used a tonne of pure silver each year to make the photographic emulsion and there were two paper coating machines that were each capable of producing a mile of paper a day. The first machine in the late 19th century only had a capacity of 200 feet a day. The coating rooms where this happened were 250 feet long.

Even at this early stage, the factory was already very self-sufficient. It incorporated engineer’s, carpenter’s and electrician’s shops to make and maintain all of the equipment.

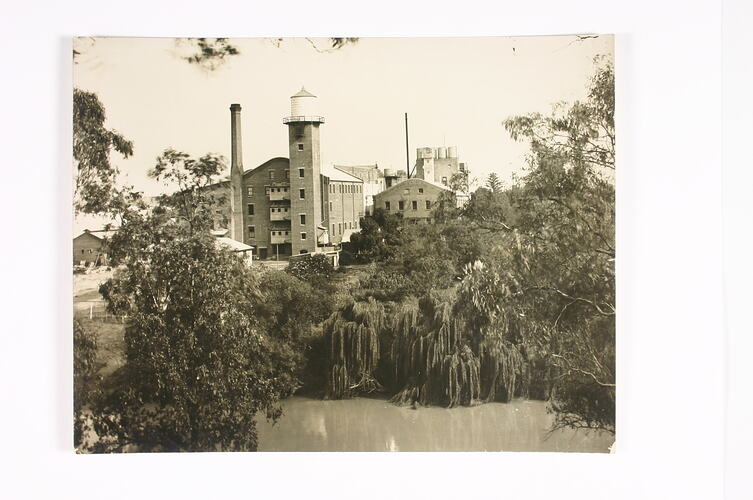

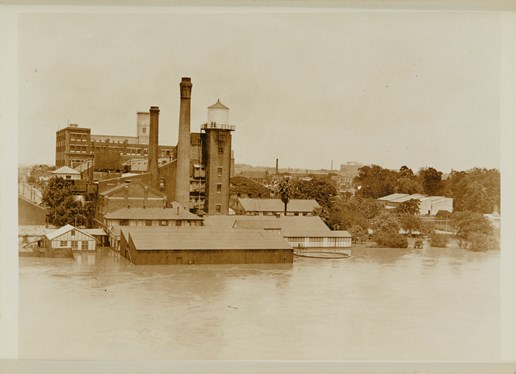

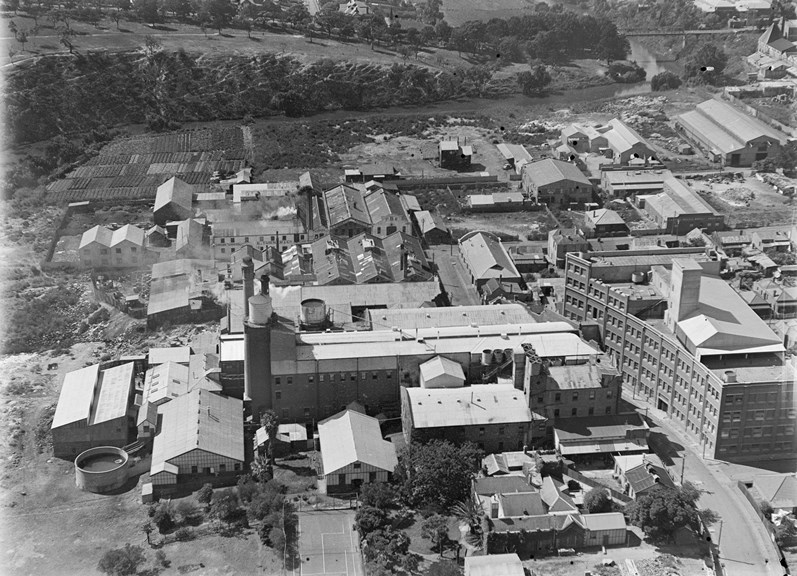

In this image taken from the Studley Park side of the Yarra River between 1915-1925, the site already looks crammed with a variety of factory buildings.

Products Made at Abbotsford

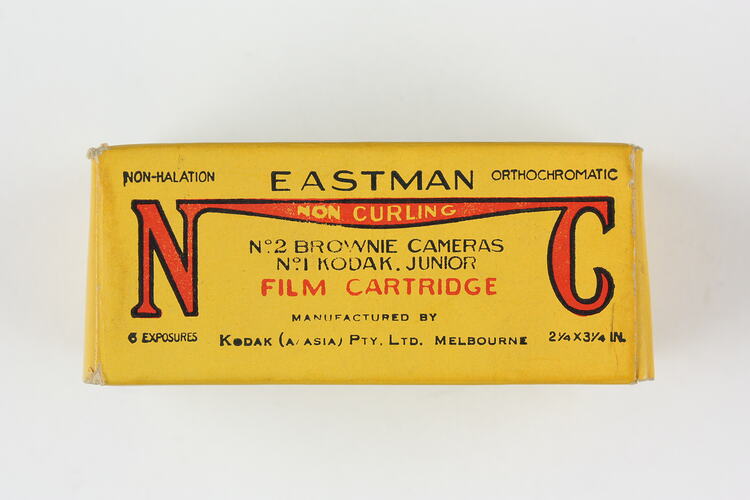

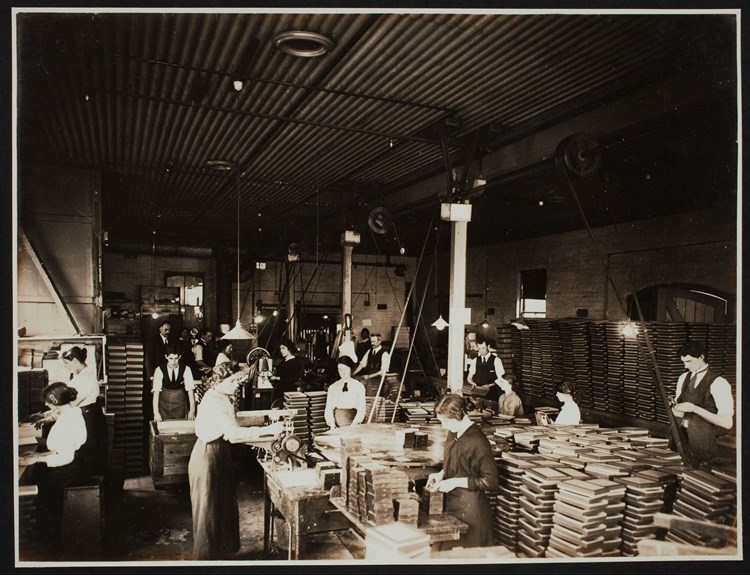

Some of the products being made by the banks of the Yarra River at this time included Kodak NC (Non-Curling) film, Austral standard plates, Austral lantern plates, Austral bromide papers, Austral Nepera gaslight paper, Velox paper, photographic mounts and Kodak chemicals to suit local conditions.

As demand for photographic products continued to increase worldwide in response to a growing interest and uptake in consumer photography, the Abbotsford factory become a bustling and thriving factory with ever-growing production.

By 1918 Thomas Baker was already looking around for land to build a new factory on, aware that his current property was getting very full with buildings and activity.

He bought 117 acres of land that was a former golf course in Kew, not planning to do anything with it for at least 3 years. Unfortunately he realised it was too hilly and sold it for residential estate development.

Kodak Australasia continued to be very successful, and its factory expansion kept going full speed to keep up. By 1921 there was over 15 acres of factory floor space.

In 1928, a new small building, known as Building 4, was squeezed in next to the large paper coating and film spooling building.

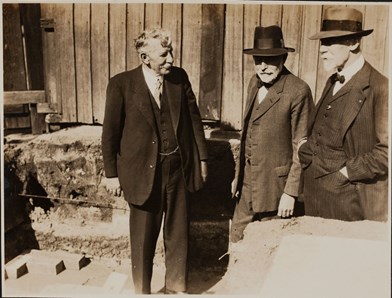

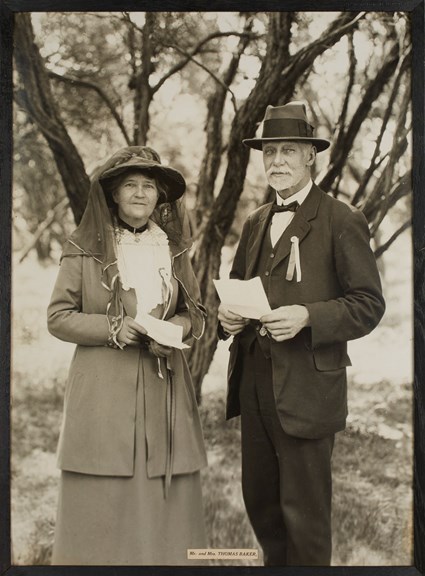

By the end of that year Thomas Baker had died unexpectedly following surgery, making these photographs of him with his staff at the building commemoration, the last photographs taken of him that can be found in the Kodak Heritage Collection.

Baker’s vision for a new factory had not been realised in his lifetime, but a new leader was about to put his stamp on Abbotsford and Kodak Australasia, and bring Baker’s ambition into reality.

With Thomas Baker’s death it was the end of an era, however a new young leader was now in charge. JJ Rouse’s son Edgar Rouse was now managing director, and he continued the pace of expansion and vision for the company shown in Baker’s time.

In 1930, a huge new multi-storey building curving around the south side of Southampton Crescent was constructed. Known as Building 23, it had a new film coating track that was built to accommodate X-ray film coating. It was also used to store raw paper base, and store and despatch light sensitive emulsion coated product. X-ray film had first been made at Abbotsford in 1925 by Thomas Baker, and the new building allowed an expansion in its production.

The new X-ray building was connected to the existing paper coating building across the road by a covered platform between the second and third storey buildings.

This building still exists, and is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register – so go and check it out if you are in Melbourne. It is now owned by Carlton United Brewery.

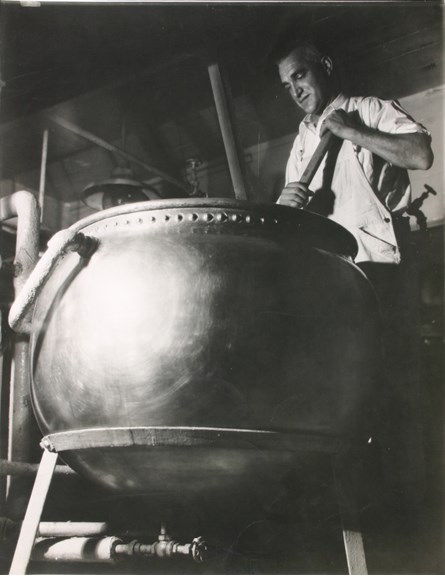

The most important manufacturing work that was undertaken at Kodak’s Abbotsford factory was the production of photographic plates, film and paper. This involved making light sensitive emulsion and coating the raw material with it – glass, film or paper.

This unique work had to be done in the dark. If the product was exposed to light during manufacturing it would be ruined.

This had its challenges.

According to John Garrett, a former worker from the 1930s-50s period, it might take the staff 20 or 30 minutes to adjust to the panchromatic light levels before they could work safely and productively.

In some of the dark areas, blind men and women were employed to work, because they were very sensitive to touch and could handle sensitised products in the dark highly efficiently.

Each product type had its own lighting requirements, and the emulsion that was being used for the day would determine what colour filter and level of light the staff would need to use in the emulsion making and coating areas.

Freda McGregor, later Freda Cuthbert, was just fifteen years old when she began in the Plate Department in 1935. She recalled that when working in the dark areas:

We used to have to walk along the passage singing out ‘Mind me! Mind me! Mind me!’ … there were small rooms that came off some of the passages… and occasionally we would bump into someone, if someone was coming out of one room, and you’d have to be careful if someone was wheeling a trolley… with glass plates.”Freda Cuthbert (nee McGregor)

A Full Sensory Experience

Ed Woods, who was a young chemist in the 1950s at Abbotsford, and later managing director of Kodak Australasia during the 1980s and early 90s, remembered that:

“I always knew when we were making x-ray emulsions because x-ray had a high level of ammonia in it, and we used fifteen-normal ammonia, which is virtually fuming ammonia, and you know, I don’t know how the guys didn’t cry when they were making those emulsions because the ammonia was quite strong.

And walking into the coating building I always knew when we were coating Kodacolor, you could smell the solvents out of the sensitising dyes, so when you’re on colour film there was this smell of solvents in the air, when you were on x-ray it was quite different, so you could pick what product was actually being made in either the emulsion department or the coating department, depending on the smell.”

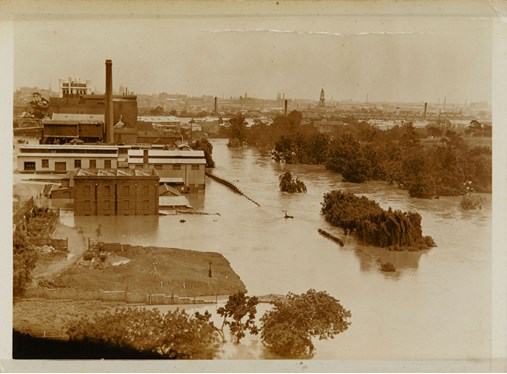

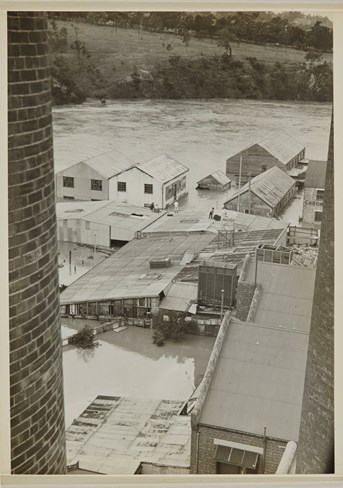

This image from across the Yarra River, and the aerial view of the Kodak factory, show the tennis court, gardens and orchard trees still in existence on the Kodak property in the 1930s.

However, these were soon to disappear for new factory buildings, as production pressures mounted at Abbotsford.

In 1936 the Kodachrome building was added to the site to process Kodachrome film. This was followed soon after by construction of a new Plate Department building. Both took up space where the original Yarra Grange gardens had been. There were about 25 buildings on the factory site now.

Yarra Grange Put to Work

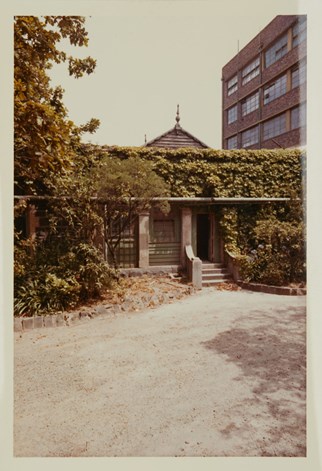

During the 1930s, well after the Bakers had moved out, and after Thomas Baker had died, their original residence Yarra Grange was rearranged to be useful for manufacturing work.

The Powder and Solution Department operated out of part of the former home until about 1950, while the director’s dining room was located in another part of the house for a time, until the Coating Technical Group replaced it in the early 1950s.

A Residence Once Again

During this time a new family moved into Yarra Grange.

From about 1938 until the early 1950s, Yarra Grange housed the Clarke family, who lived there while they worked for Kodak. The house continued to serve its new industrial purposes in other parts of the building.

Gladys Clarke was the cook for the directors' dining room, which was now located in Yarra Grange, along with the kitchen and food store. Her husband Henry worked in silver recovery at the Abbotsford factory, and later, after a work-place accident, he tended the factory gardens.

Their son Harry, twelve when he moved into Yarra Grange, grew up within the unusual environment of a factory, only moving out when he was in his early 20s.

Harry’s bedroom was upstairs in an area which, in his later years, he recalled “was a little bit like a castle with the battlements on the top, bluestone with ivy growing up all around the walls”. Despite the house now being a working area of the crowded factory, Harry fondly remembered his childhood home as a place of beauty and joy. Talking about his bedroom he reflected:

On the path below was a hedge of lavender, and after the rain on a summer night you could get this beautiful perfume. It stepped out … onto a sun-balcony which looked down the sloping block towards the river, and Studley Park was on the other side, very idyllic.Harry Clarke

When young Harry Clarke lived at Yarra Grange, bottles of chemicals from Thomas Baker’s early experiments and photographic production work were still on the floor of the cellar, 50 years later. And in a lovely quirk of history, linking moments in time, Harry often processed his own photographs in this same cellar, although Harry was printing photographs from plastic, rather than glass, negatives.

It wasn’t surprising that Harry Clarke felt at home living at Yarra Grange, despite being within a factory complex. It was originally Thomas and Alice Baker’s home and prior to them purchasing it, Yarra Grange had been the home to several other early Melburnians and featured one of the city’s earliest orchards, as well as extensive historic gardens.

These established domestic gardens and the river front location made living, and working, at the Kodak factory a more pleasant experience than might otherwise have been expected in a manufacturing environment.

In the early 20th century there were established chestnut, pear, oak, willow and magnolia trees, as well as wisteria and ivy framing a manicured lawn setting with flower beds.

Former staff member Betty Radstake recalls the gardens at Abbotsford, and her working life at Kodak.

Bench seats were dotted around the grounds to eat lunch on and there were the lawns to relax on or the river bank to sit on.

A tea-room for staff to eat their lunch in was set up in about 1919-1920. Tea, milk and sugar was provided, and there was a borrowing library in one corner.

Sport and Recreation

Kodak staff enjoyed recreation in the outdoors during their lunch breaks. The original Yarra Grange tennis court survived until the mid-1930s, when it was built over by the new Plate Department building, but there was a basketball court available, and there was still plenty of open grassed areas to play footy or cricket, although this shrank as time went on.

Val Bell talks about her experience playing basketball for Kodak, as well as her working life at Abbotsford during 1937–1944.

A Family Culture

Thomas Baker was a benevolent boss, and he hosted his staff at annual picnics, sometimes at his home Yarra Grange on the factory site and other times at picnic grounds by the beach or in the countryside.

In 1900, the Thomas Baker hosted his Baker & Rouse staff at a garden party at Yarra Grange. Sports and refreshments were had in the grounds and then the guests moved to the Baker’s house where music was played. This highlighted the close relationship between Thomas Baker and his staff, and the family culture that he cultivated – which was particularly facilitated by the Bakers living onsite at the factory at times like this.

On another occasion, in November 1922, before the Bakers travelled overseas, Thomas Baker and his wife Alice hosted their staff at a picnic at the Mornington recreation reserve, near their country estate, Manyung.

They provided a specially chartered train for the occasion, which took their guests from Flinders Street Station to Mornington. There was a band, dancing, a sports programme, and a photography competition, and even a display of aeroplane stunts.

In 1920, Thomas Baker hosted the inaugural social evening at the new Kodak Recreation Hall / Tea Room, where staff performed a programme of entertainment. During the event he donated a piano to the employees for their own use and for future performances. He said:

“it was his intention to foster the social element of the employees’ lives in order to create a harmonious feeling”Thomas Baker

The Abbotsford staff in turn returned their appreciation of Thomas Baker’s kindness. When the Bakers and Miss Eleanor Shaw travelled overseas, there was usually an event of some kind wishing them bon voyage or welcoming them home, such as in 1900 when the Victorian staff gave Mr Baker a gentleman’s travelling case or in 1924 when the Collingwood Town Hall was full of staff for an evening of celebration and welcome home toasts.

A Healthy Workforce

Kodak factory staff benefitted from Thomas Baker’s care in other ways too, such as through the medical service he facilitated, no doubt inspired by his early career as a chemist and ‘surgeon dentist’ who had studied medicine for a year.

During the 1919 Spanish Flu epidemic, Thomas Baker installed a device called an Inhalatorium. Staff inhaled steam carrying a sulphate of zinc solution which was supposed to protect them from contracting influenza.

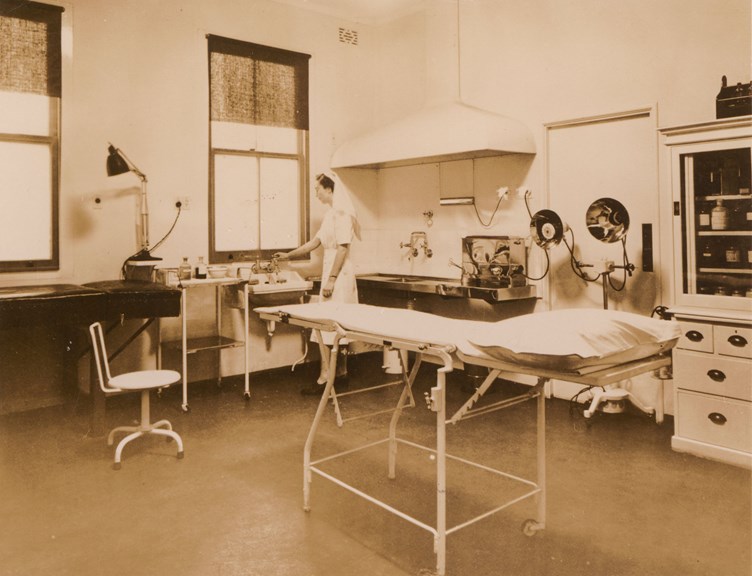

The first staff doctor was appointed in 1924, and after Baker’s death, the new managing director, Edgar Rouse, built a dedicated medical facility at the factory, in 1945. It included a consulting room, rest rooms for staff, a waiting room and a surgery – and came with a consulting doctor and nurse.

Edgar Rouse continued the paternal style of management during his time as director at Abbotsford. He too hosted dinners for staff, such as after WWII, and provided free soup during the 1930s depression to all staff. During the 1950s he upgraded the staff and foreman’s dining rooms.

During Edgar Rouse’s leadership, various benefits were continued and new ones introduced for workers at Kodak. These included superannuation and life insurance, a co-operative housing society, and staff discounts on Kodak products. Company booklets outlined these for staff.

View the complete induction booklet on Museums Victoria collections website.

Despite re-organising and streamlining production in existing buildings, and squeezing in new buildings where they could, Abbotsford was bursting at the seams.

As Ed Woods noted, “it grew like topsy, there were lots of buildings…”

It wasn’t just the buildings that were under pressure, the equipment and work environment was also getting old and tired, although it was well maintained by the highly skilled Kodak engineers to still deliver excellent quality product.

Listen to Brian Phillipson talk about his early days at Abbotsford in the 1950s.

Listen to Jim Heally talk about his early days at Abbotsford in the 1950s.

New Horizons

In 1943 Kodak bought land for a new factory, in Coburg on the northern outskirts of Melbourne.

In 1950 Kodak bought the old Barnes Honey factory in Swan Street Burnley to house the photofinishing (developing and printing) and photochemical departments.

The factory had outgrown its original site and could no longer meet the demands of production.

Last Days

Finally in the late 1950s, the company began building a new factory on farm land in Coburg. The first stage of this factory was opened in 1961 and the Abbotsford operations gradually transferred to the new site over the next few years.

Listen to Michael and Lucy Mikedis talk about their working lives at Abbotsford and Coburg in the 1960s and 70s.

In April 1965, Thomas Baker’s original home, Yarra Grange, was demolished as the company prepared to vacate the Abbotsford site.

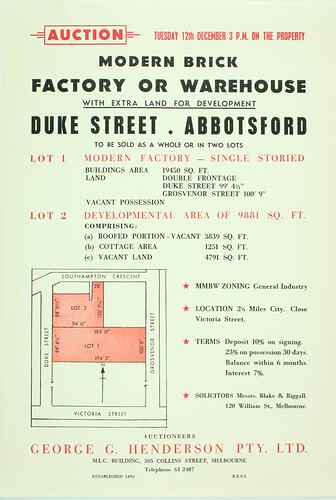

The following year the factory was put on the market and was sold in January 1967. Parts of the site had already been sold earlier that decade.

Before its disposal, some symbolic elements of the Abbotsford factory were transferred to the new Coburg site. A retaining wall was constructed of bluestone from the former home of Thomas Baker. This was built near building No. 20, the Color Print & Processing Department.

The landscaping at Coburg also included an oak tree planted in 1961 which was grown from an acorn taken from the original Abbotsford site.