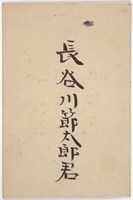

Setsutaro Hasegawa

Grandpa Hasegawa was not a gregarious community character, he was happy tending to his Japanese garden, breeding goldfish and birds. He was the patriarch of the house and meals did not begin until he was seated. After dinner he retired to his room and studied, read and kept diaries.

Andrew Hasegawa, great grandson, 2021

Setsutaro Hasegawa was born in Japan in 1871. An eldest son, he was raised under the expectation that he would care for his parents in old age and inherit the family estate.

Setsutaro was working as a school teacher when in 1897 he decided to improve his English and head to Australia on the ship Yamashiro Maru.

He first worked as a domestic for Arthur Tuckett, known for exploiting his workers. In 1900 he became one of the proprietors of Sunrise Laundry in Prahran. He would remain in the laundry industry throughout his life.

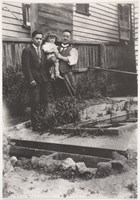

In 1905 Setsutaro married Australian-born Ada Cole and they had three children: Leo Takeshi in 1906, Moto Kozo in 1907 and Joe in 1911. During this period the family moved to Ballarat where Setsutaro set up a laundry and he and Ada won prizes at poultry and dog shows.

Ada left Setsutaro in 1914, leaving him to raise three children alone. He returned to Melbourne to live with his tailor and friend Ichizo Sato in South Yarra, and later relocated to Geelong to establish a laundry business and live with another Japanese friend, Motoshiro Ito. Setsutaro had earlier gained his inheritance after the death of his father but, to his family’s likely consternation, never returned to Japan. In 1927 he purchased his own home in Geelong; he had a car and was a man of means.

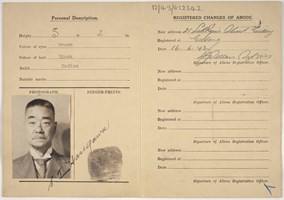

On 8 December 1941, Setsutaro was arrested as an enemy alien just before his seventieth birthday and sent to Tatura internment camp. He was released in 1943 but his laundry had closed, things were tough and being Japanese had become an identity to hide. Setsutaro remained in his home, family close by, and he died in 1952.

From Australian to alien

In April 1930, a group of close friends had a picnic in the countryside near Geelong. They took photos to remember the outing. Setsutaro Hasegawa drove everyone in his car, with George Furuya, his wife Ada May, Motoshiro Ito and his wife Bertha all squeezed in with a picnic basket and blanket. Setsutaro is wearing a suit tailored for him by another good friend Ichizo Sato, not present that day.

Eleven years later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbour and everything changed.

On 8 December 1941, police knocked on Setsutaro’s front door at 21 Little Ryrie Street Geelong and arrested him as an enemy alien. Motoshiro, George and Ichizo were also arrested. Despite all being married to Australian-born women, having Australian-born children, and living away from Japan for over thirty years, their lives were turned upside down.

4,301 Japanese civilians were interned in Australia; few were excluded or released early. Nearly all were repatriated or forcibly deported after World War II unless Australian-born or had an Australian-born spouse. These spouses, such as Ada May and Bertha, lost their British (at that time) citizenship.

Like Setsutaro, George Taro Furuya was an elderly man when he was interned. His early release in 1943 assisted Setsutaro’s eldest son Leo, who was serving in the civilian military forces, to petition on his father’s behalf. Motoshiro remained in detention until the end of the war. All three men were lucky and avoided deportation.

Ichizo Sato had his tape measure taken from him before being sent to Tatura. Although he had arrived in 1901, been married for over 20 years to Eva Elizabeth Chue, an Australian of Chinese heritage, Ichizo was deported to Japan in 1946.

It was a time when it was hard to be Australian and Japanese. But, reflects his great grandson Andrew Hasegawa:

Grandpa Hasegawa knew who he was. There was no confusion triggered by internment, war and 55 years living in Australia. He died a proud Japanese man.

When the horrors of Japanese POW camps became known, suspicion and animosity became hatred. For the children and grandchildren of these Japanese-Australians, decades of identity confusion and denial had just begun.

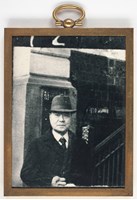

Family portraits

Tailor by trade, tailored by nature

Setsutaro took great care in his appearance. He purchased his suits from his friend Ichizo Sato, a fellow migrant from Japan who had arrived in Melbourne in 1901. Ichizo eventually set up his tailoring business in Toorak Road, South Yarra. Many photographs of Setsutaro show him wearing a Sato suit.

When Ichizo Sato was interned as an enemy alien in 1942, one of the few possessions he had with him was his tape measure.

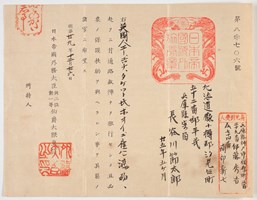

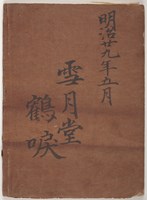

Things from home

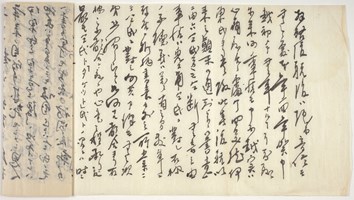

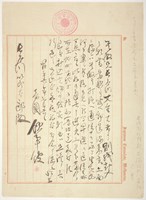

When Setutaro Hasegawa migrated to Australia in 1897 he brought just a few precious possessions with him. They represent the country he was leaving behind and the new life and language he would encounter.

Staying in touch

Setsutaro may not have intended to stay in Australia permanently. When his father died he inherited the family property and was expected to return to Japan as head of the household. Setsutaro, who by this time had married a local woman and was raising two children, had other ideas. He never returned to Japan.

Settling in

It can’t have been easy for Setsutaro. Prejudice against ‘mixed’ marriages was common, and he had three children whom he would raise as a single parent. He established a laundry business, and although ineligible for naturalisation under the 1903 and 1920 Naturalisation Acts, Setsutaro purchased a home in Geelong, and enjoyed his friendships and family there.

Acknowledgement

The Immigration Museum wishes to acknowledge the research assistance of Andrew Hasegawa and Lorinda Cramer in the development of this display.