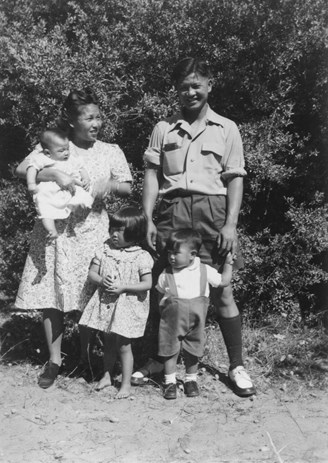

May and Sydney Louey Gung

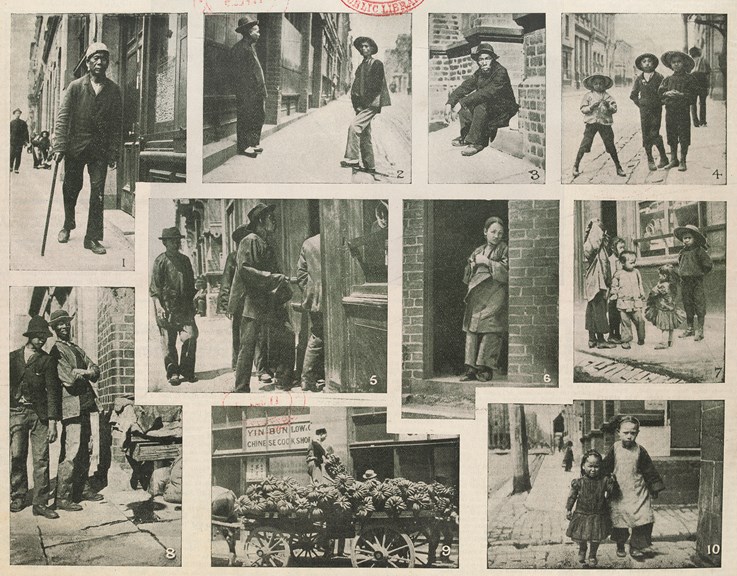

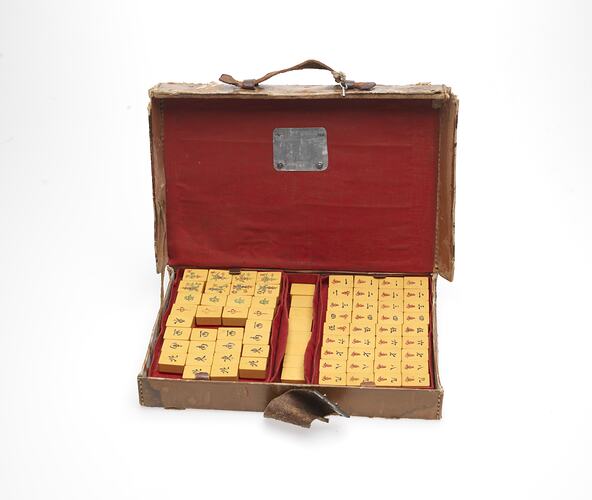

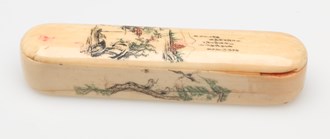

Little Bourke Street Melbourne, 1890. Horse-drawn carts, furniture makers, laundries, fruit and vegetable businesses, incense, opium and the clacking of mah jong tiles.

'Tong Yun Gai', as the Chinese residents called Little Bourke Street and its adjoining lanes, continued to expand. It was here, in Celestial Avenue, a small lane off Little Bourke Street, that Yen Pein, known as May, was born.

By 1900, this part of Chinatown was diverse, noisy and crowded, a place where Chinese and non-Chinese people interacted, gambled, did business and shared gossip over tea in clan-owned general stores. May possibly played with children from different families and purchased nuts or sugar cane from street hawkers.

May grew up in China and attended a Christian school, and it was there she married Sydney Louey Gung who had returned temporarily to China from Melbourne in 1912.

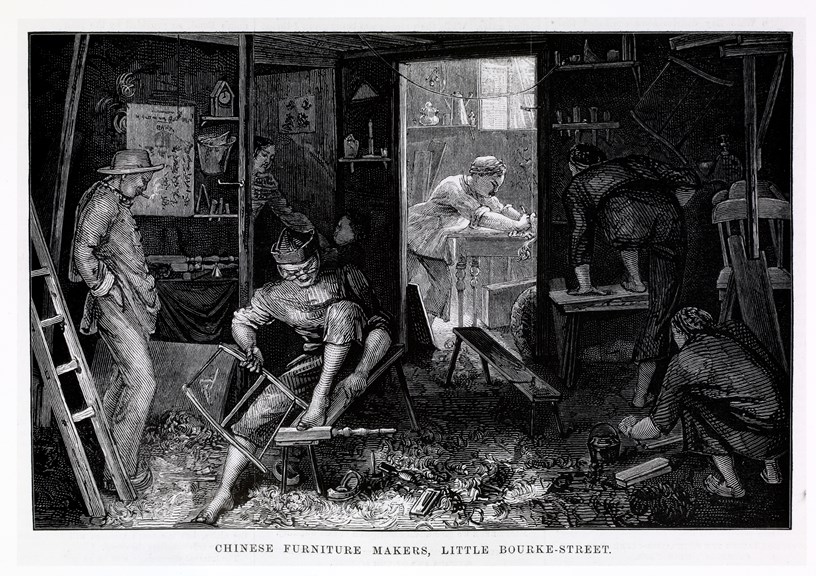

Sydney was born around 1879 in Canton (Guangzhou) in southern China. He arrived in Australia in his early twenties and after four years was working in Melbourne – first in his own carpentry shop in Little Bourke Street and later as a foreman and fruit department manager in the import and export business owned by his older brother Harry Louey Pang.

For Sydney, adjusting to life in Victoria was not always easy. The Gung family recalls he was once attacked by local 'larrikins' who cut-off his queue (braid), a common act of assault against Chinese men.

May and Sydney had ten children between 1914 and 1932 with the eldest Maisie and the youngest Christine born in China. The family travelled frequently to their home country, jumping through bureaucratic hoops in order to leave and re-enter. During World War II, three of the children lived in Australia with their parents; the other children remained in China to complete their education.

The family lived in homes in Newmarket, North Melbourne, and Carlton. Sydney died in 1954, May in 1969.

Not quite Australian

In 1901, Chinese merchants erected a beautiful, pagoda-inspired arch in the centre of Melbourne to celebrate Federation.

Two days before the opening of Parliament around 200,000 people were reported to have watched the Chinese dragon procession pass through the city streets.

Yet Chinese immigration to Australia was severely restricted, naturalisation impossible to obtain and Chinese Australians who left temporarily needed permission to return. The decades after the 1850s gold rushes had been punctured by discrimination, resentment, even violence.

The Chinese population plummeted from about 26,000 in 1901 to about 12,000 in 1947. Nevertheless, this vibrant community managed to settle, run businesses, raise families, and establish associations.

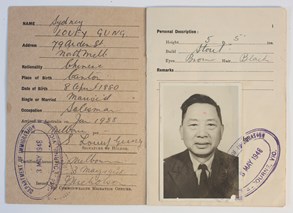

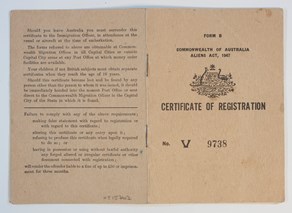

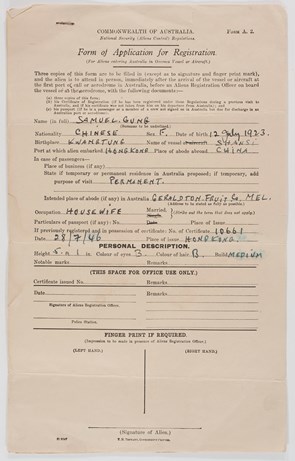

Ironically, the Immigration Restriction Act (1901) generated vast numbers of government documents which now assist in the tracing of Chinese-Australians. The Gung family paper trail shows how they negotiated their residency in Australia and return trips to China.

Many Chinese families chose to be mobile, in order to arrange a Chinese education for their children, set up businesses, and even eventually retire in their home villages. Before any overseas journey Sydney and his China-born children were required to apply for certificates exempting them from the dictation test to ensure their re-entry.

Women, who migrated from China in vastly smaller numbers than men, are harder to find in the records. Sometimes just listed as a name on their husbands’ documents, and after 1903 frequently denied permanent admittance despite their marital and maternal status, they are only occasionally visible. Yet they were wives and mothers who were raising families, supporting working husbands, even running businesses, and participating in religious, social, and business organisations.

It was not until 1966 that the Australian Government allowed the wives and children of Chinese-Australian men to settle here permanently, ending decades of discrimination.

Family portraits

Wood, fruit and milk

Sydney Louey Gung worked as a cabinet maker and fruit agent for Harry Louey Pang & Co, his brother’s fruit, produce and import/export company.

Despite the Commonwealth Immigration Restriction Act (1901), exemption arrangements could enable the company to employ Chinese-born staff as well as Australian-born Chinese male workers.

In 1938 Sydney was employed by the Geraldton Fruit Company at Melbourne's Victoria Market, and worked there until the 1950s.

His three sons, Victor, Samuel and Melbourne were also employed there. Sydney also owned a milk bar in Carlton.

Home and community

Chinese women in Victoria raised their children, undertook domestic duties and some even owned and managed businesses in Melbourne's Chinese quarter.

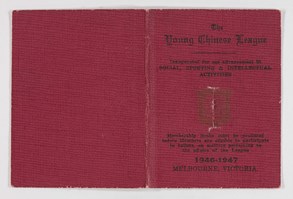

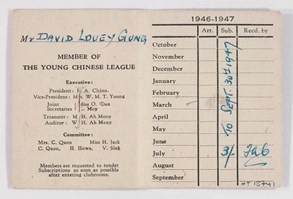

Market gardens and import businesses enabled the home preparation of more traditional Chinese foods and beverages. Women also participated in religious and social associations such as the Young Chinese League.

The next generation

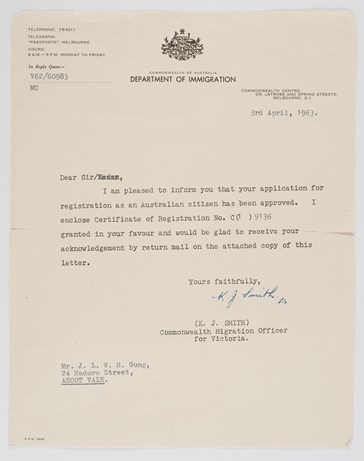

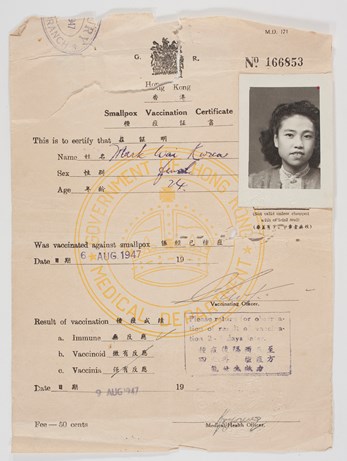

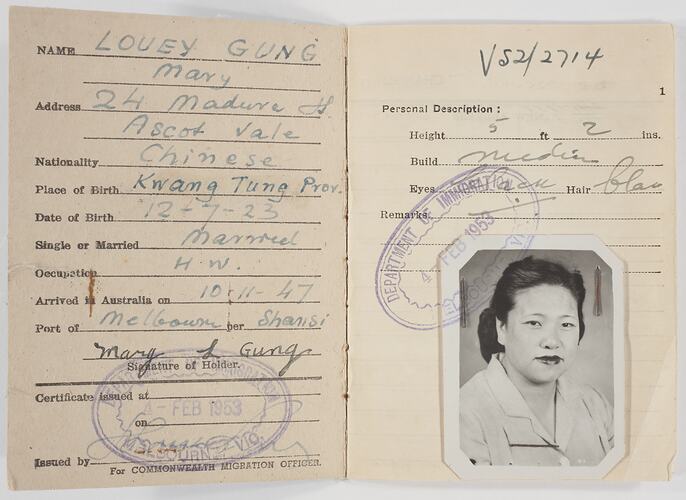

Sydney and May’s son Samuel was born in Carlton in 1920 but completed his education in China. After World War II, having served with US Forces, Samuel married Mark Wai Kwua (Mary Louey Gung) and had two children, Ling Po (Phyllis) and Wing Young (Jeff).

In 1947, the family came to Melbourne and had four more children. They were befriended by Arthur Calwell (Federal Member for Melbourne) who advised them on how to apply for Australian citizenship, finally achieved by Mary in 1962.

See the exhibition

Immigrant Stories is now showing at the Immigration Museum.

The Immigration Museum wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the Chinese Museum Melbourne in the development of this display.

Find out more