Masumi Hiraga Jackson

Alone in a new country in 1987, Masumi had a critical decision to make – stay in Melbourne or return home to Japan.

Masumi Hiraga was born in 1935 at Nirasaki, west of Tokyo. One of ten children, her three brothers died young, leaving seven daughters. Masumi’s father Tomoichi ran a silkworm farm and orchard. He was a quiet man and a strong disciplinarian.

Masumi's mother Kino was a highly skilled weaver. She wove silk cloth, sent the material to be dyed and then hand sewed the cloth into kimono. The Hiraga family were considered very fortunate to have such clothing after World War II when goods were scarce.

Against her father's wishes, Masumi studied librarianship and Japanese literature at Toyo University, Tokyo and taught in high schools and universities. Meanwhile, most of her sisters had made traditional preparations for early marriages, learning dress and kimono making, calligraphy and tea ceremony.

In 1977, Masumi met an Australian, Thomas Jackson, who was in Japan for a conference. In 1984, Masumi finally agreed to marry him, and settled in Melbourne in 1985. Thomas died suddenly from a heart attack three years later and Masumi was left with a sad dilemma – stay or go.

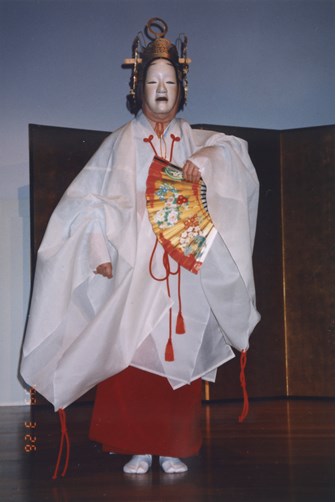

She decided to remain in Melbourne and immerse herself in Noh theatre, Ikebana and paper doll-making in Melbourne – skills she had been developing for 50 years. Along with the traditional Japanese tea ceremony, she shares her skills through performance and teaching.

Masumi returns to Japan every year to see her family, continue Ikebana lessons, practise her Noh performance and purchase materials for doll-making. But Melbourne is her home.

Maintaining traditions

Immigrants to Victoria have always found ways to keep their diverse cultural traditions alive in their new home.

They have formed associations and clubs, built places of religious worship, published language-specific newspapers, and imported and made foods from home — informed by the skills, knowledge and beliefs they have brought with them.

As far back as the 1850s, the Melbourne Hebrew Congregation built its new synagogue, Scottish Caledonian societies were established and the Italian Lucini family began producing pasta in their factory in central Victoria.

Such overt cultural practices have not always been encouraged. Australian immigration policies primarily favoured British immigrants, as well as people from cultures that could be easily assimilated into a predominantly Anglo-Australian society.

Since the 1970s, political shifts to multiculturalism acknowledged the value of diversity and equality in all its forms, recognising the importance for people to be able to express their cultural identity. Nevertheless, issues such as social integration, religious tolerance and a single Australian identity, continue to inform public debate.

The maintaining of some cultural traditions can sometimes result in customs frozen in time. A particular weaving pattern, wedding custom or dance, which has been transported here and practised without change in Victoria, may have evolved or even disappeared in its country of origin.

Masumi Hiraga Jackson continues to teach, perform and pass on her knowledge and skills of traditional Japanese theatre, doll making and Ikebana (flower arrangement) to Japanese and non Japanese audiences — connecting living arts between the old country and the new.

Objects of meaning

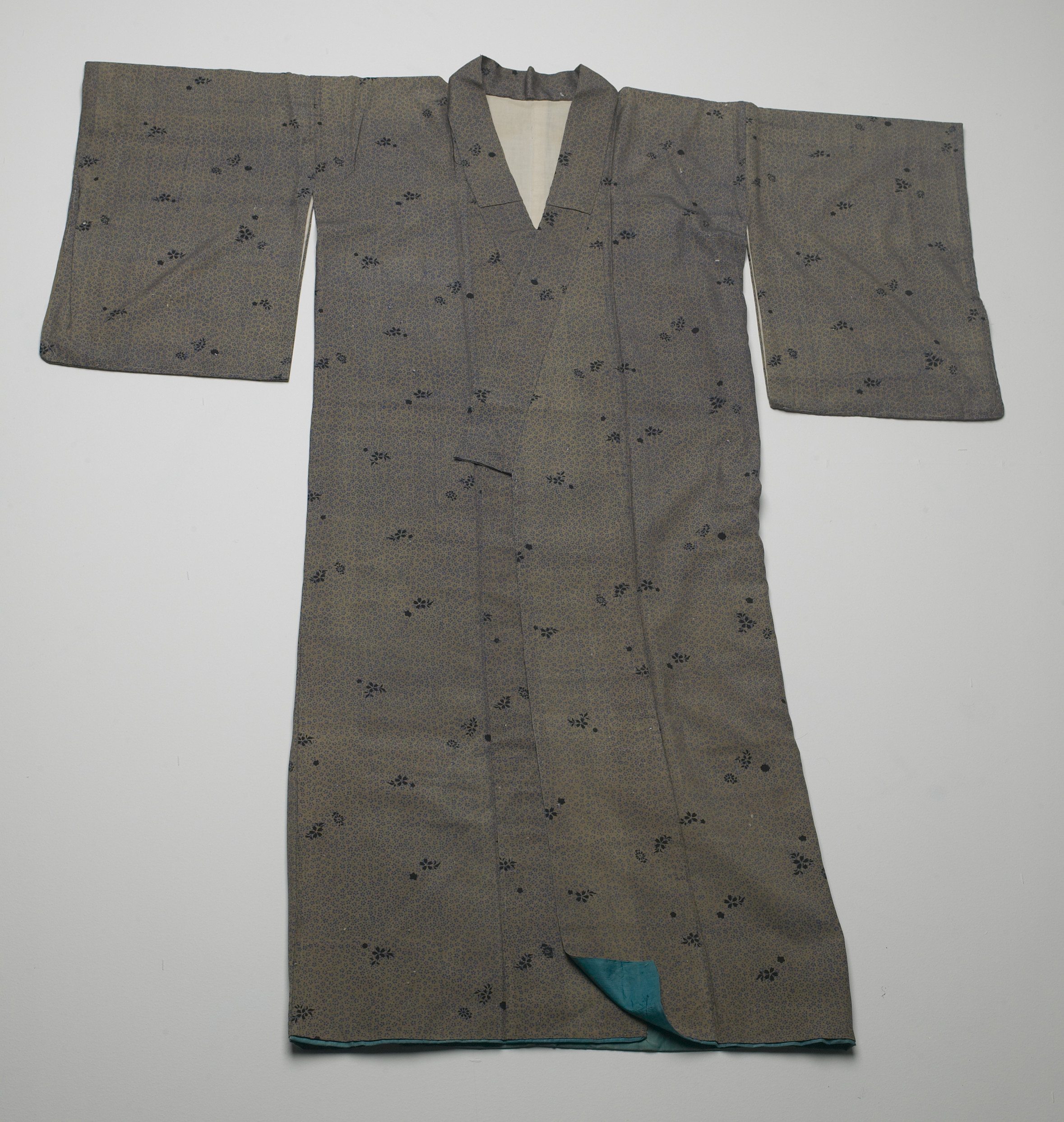

Kimono

The women in Masumi's family have woven and sewn kimonos since the early 20th century. Kimonos are traditional Japanese garments, worn by men and women.

Kimonos vary in style, colour, pattern and fabric depending on the occasion and the wearer.

Masumi’s kimonos hold special meaning for her, as mementoes of her homeland and as cultural artefacts which she wears socially and for performances.

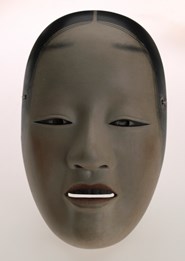

Noh theatre

Noh is an important form of classical musical drama performed in Japan since the 14th century.

The principal actor, and sometimes minor actors wear masks. All performers, including the chorus singers and musicians, carry fans.

Masumi Hiraga studied Noh Theatre at Toyo University in the 1950s and continues to learn and practise the art at the Hosho School of Noh in Japan. She performs in Japan and Australia.

Paper dolls

Paper doll-making in its simplest form dates back over a thousand years in Japan. By the 8th century, a unique method of crepe paper production was introduced to the Shimotsuke region.

The technique has been refined over time, using flexible crepe paper which is easily moulded into various shapes. The colours and patterns hand-dyed on the paper reflect kimono designs, while the characters are taken from Japanese folk stories and Noh theatre.

Tea ceremony

For Masumi, the traditional Japanese tea ceremony is an art form, one of beauty, tranquillity and simplicity of movement. Tea ceremony is the ritualised way of preparing, serving and drinking 'matcha' (powdered green tea).

Tea drinking was introduced from China and first practised only by Buddhist priests, and then by samurai warriors. It gradually spread throughout Japan. Greatly influenced by Zen Buddhism, the tea ceremony has in turn influenced many aspects of Japanese culture.

See the exhibition

Immigrant Stories is now showing at the Immigration Museum.

Find out more