Girlhood

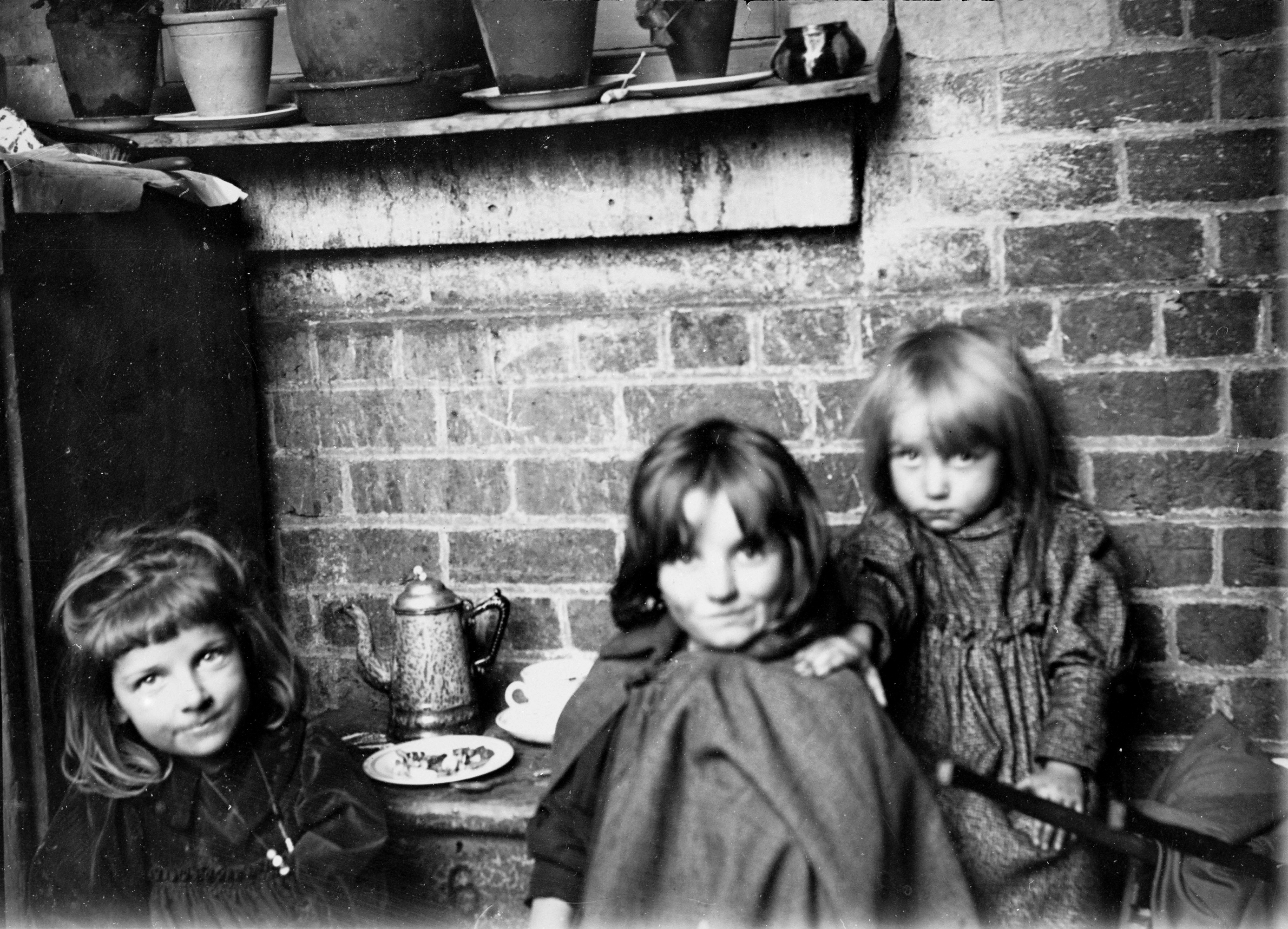

Fair and fascinating: girls in 19th century Victoria

Our Australian girls are fair, fascinating, accomplished, and more useful than their English sisters.

—Kathleen Lambert, 1890

Girls in 19th century Victoria were expected to be useful.

Many of their parents were migrants. Other girls migrated with their families, enduring long sea voyages before making their homes in Melbourne, regional towns and rural areas.

Most homes were small, but families were usually large. Sisters would share bedrooms and often beds. Girls had few items of clothing or possessions of their own.

Girls had to help around the home. They would cook and clean, sew and mend, and look after their siblings. Even girls from wealthy families learned needlework and household management.

In their spare time girls sewed, read, made scrapbooks and gathered collections such as shells or stamps.

Sometimes they played imaginative games with siblings and friends.

After education became free and compulsory in 1872 most went to school, though their education usually finished by the age of 14. Many also attended Sunday School and church, or other religious activities.

Older girls usually stayed at home until they were married, typically in their early twenties. Few professional paths were open to girls. Some worked as maids or in factories; others became teachers or governesses.

Girls’ voices are often absent from history. The stories we share here are mostly those of British and European girls, which reflects the focus of the Museum's 19th century collection. They show us that girls could be adaptable, creative and fun-loving, and made the best of challenging times.

Mending and making

Only the usual routine of practice and sewing. I commenced the second pair of drawers today.

—Catherine Deakin’s diary entry, 12 January 1866, aged 15

The daily ‘usual routine’ of girls in 19th century Victoria often included sewing.

Girls from a range of backgrounds learnt to craft and stitch. It was central to their education because it gave them the skills they needed to make and mend clothing for their future families, and to furnish and decorate their homes. Sewing skills were also required for many jobs open to women.

Catherine Deakin, sister to future Australian Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, was no exception. Though from a wealthy family, she sewed every day, and often read and practised the piano at her home in South Yarra.

Plain sewing to make and mend clothing was a key skill. Anne Trotter was a teenager when she learnt how to stitch miniature examples of shirts, dresses and socks while a student at the Female Free School in Collon, Ireland. She brought her precious sewing specimen book when she migrated to Melbourne in 1844, at the age of 23.

Girls also learnt to embroider, often making samplers to practice new skills. They embroidered the alphabet and numerals, as well as motifs of varying complexity, finishing their samplers with their name, age and the year.

Eliza Winter made several needlework samplers between 1847 and 1853, the first one when she was only five years old. She lived at 172 La Trobe Street, in the heart of the city, where her father had a cabinet-making business.

Sadly, Eliza died of a 'fever', likely colonial fever (typhoid), at the age of 11. Child mortality was much higher in the 19th century due to sickness or injury. Epidemics frequently swept through Melbourne.

Ethel Punshon could already sew and make clothes for her dolls by the age of six. Her mother encouraged her to turn to ‘fancywork’ and make decorative objects for the home.

Ethel made a newspaper holder which was exhibited in the under-sevens category at the 1888 Melbourne Centennial Exhibition. Ethel ‘won first prize of two guineas and a certificate’. Her family travelled several times from their home in St Kilda to the exhibition to visit Ethel’s piece.

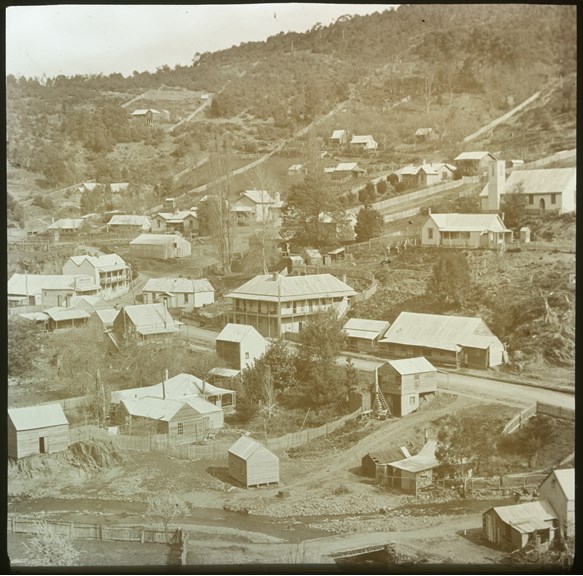

In 1884, at the age of 14, Margaret (Maggie) Knopp began to compile a scrapbook. Daughter of Irish and German migrants (her father was a miner), she grew up at Woods Point, a small gold mining settlement east of Melbourne. She used newspaper cuttings and mass-produced scrapbooking images to create scenes and patterns, interspersed with poems, ditties and some drawings.

Maggie’s scrapbook shows she was intensely romantic: flowers, love poems and courting couples appear on her pages. Though Maggie’s daily life is not noted in the scrapbook, there are hints of her attachment to home. She has used ferns and leaves, likely collected from her neighbourhood, as stencils for ‘splatterwork’.

Acknowledgement

The Immigration Museum wishes to acknowledge the curatorial work of Catherine Gay in the development of this display.