First Impressions

We have so much in common with each other, and you just have to see past I suppose the surface area whether it be your physical appearance, language barriers or religious barriers. When you actually sit down and interact with someone and you go past those barriers, you find you have so much in common with them. No matter how different things may appear on the surface, the surface isn’t the whole story.Héritier Lumumba, 2011

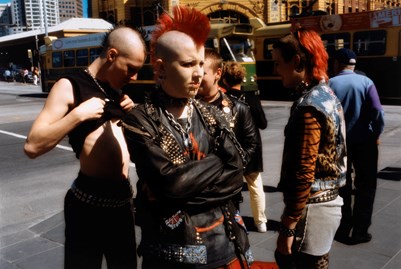

A punk haircut. Dark skin. A 'funny' accent. A walk with a limp. The smell of garlic.

We make a snap judgement and assume that we know someone. But do we really?

Can labels be helpful? Are they as accurate as we like to think? Do they mislead us?

The way we look

When I look in the mirror I don't see what other people see. I'm just Sherene. But when I meet people for the first time, they look at me differently — and the questions begin.Sherene Hassan, Melbourne, 2010

Physical characteristics are like jigsaw pieces that make up each person's appearance. Skin and hair colour, height, nose, eye and head shape are some of the many features that we inherit. The way we look has altered over time as our ancestors have moved and adapted to different environments.

Is it helpful then to separate human beings into races based on any single combination of physical features? Most scientists suggest not.

Yet we are quick to classify each other. Every day we judge people on the way they look.

Meet Brendan, hear his story.

Where we come from

I am in some ways the product of my ancestry and yet I have no idea what that ancestry is. To me, they are essentially all interesting strangers.Jack Thompson, Australian actor, 2007

A family album. Full of faces, memories, forgotten experiences.

Sometimes photos are missing. For some there are no photos at all — only questions.

Why are we so fascinated by our family trees? What is it that we hope to discover? What does it mean if we can’t complete the family picture?

Family relationships are complex — children are adopted, families blend, friends become family. We may rebel against family authority, or deny our family heritage.

Some questions may never be answered.

A family heirloom

Janet Scrimgeour imported this Limerick lace wedding veil from Ireland and wore it at her wedding in Bendigo in 1865 to Peter Brackelmann. For over 130 years the veil was passed down through the women in each generation to be worn at their weddings.

"This veil originally belonged to my great great grandmother Janet Scrimgeour, who migrated to Victoria from Scotland in 1854. It connects me to her, such a special person during my early childhood years, and to many of the women in my family. I wore the veil at my own wedding in 1958 so I too am part of its long tradition." Jean Billington, 2010

A family legacy

Claire Wieser French and her family migrated to Australia in 1951. The 'Passport of Ancestors' (Der Ahnenpass) on display was a standard booklet issued in Nazi Germany. In it people were required to record at least four generations of Aryan ancestry.

"This object reminds me of a traumatic time in my family's past. We had to prove our non-Jewish ancestry in order to avoid persecution. My mother's religion and my father's political and humanitarian sympathies made them suspicious to the ruling regime. By the end of the war, we ourselves were stateless — but we were still together." Claire French, 2010

A family lost, a family found

Nguyen Hong Duc was one of 200 children airlifted from Vietnam to Australia during Operation Babylift in 1975. Renamed Dominic, he was raised on a farm in South Australia by the Golding family and has since visited Vietnam in order to trace his ancestry. The Australian entry permit on display was issued to him in 1975.

"I was a four month old orphan when I was given this permit in 1975. Bundled up, I was handed to strangers in Melbourne. This new family gave me a new home, name and a better future. But I’ll never find my first mother and father. It’s as though the passport erased a family to create a family." Dominic Hong Duc Golding, 2010

What we are called

As an adolescent growing up, my name caused me great embarrassment and I hated anything that was Asian. How I wished to be Mary Smith.Kitty Vivekanada, Sydney, 1992

Our names can be a blessing or a burden. Love or hate them, keep or change them or constantly have to explain them.

The name we are given is our first step towards a separate identity. Names can also signal a connection to our family or a particular religion, language or community.

There are times when our name sets us apart. People ask: 'How do you pronounce that?' 'That's an interesting name. Where does it come from?' or 'How do you spell that?'

The impulse to change our name can be compelling. Getting married? Need to disappear? Feeling pressure to assimilate or fit in?

Ali becomes Alan. Xiao Yun becomes Claudia. Anastasia becomes Stacey.

Meet Vera, hear her story.

What we say and how we say it

I have come to understand that language shapes the way people think and feel, and vice versa. I often felt that I could not describe in English what I was feeling. I could not find in English exact expressions matching my bodily sensations.Kyung-Joo Yoon, Canberra, 2007

A busy street. An unfamiliar country. You’re lost. All you can hear is a language you can’t understand. Suddenly you hear words or an accent you recognise. Immediately you feel more at home.

Often we take our own language and accent for granted. Yet our words connect us to so many parts of identity — our family, literature, humour, even our dreams. What language do you dream in?

Language and accents also separate us. Some people hear a conversation in a public place that’s not in English, and feel threatened.

Are they talking about me? Why don’t they speak English?

If we lose our language we lose a part of ourselves.

Meet Carlos and hear his story.

What we wear

It was about completely rebelling against all the judgments I see in society and hip hop — the homophobia and prejudice — and just getting up there and saying 'Ha, I’m wearing a dress! Say something now!'Borce Markovski, Melbourne hip hop band Curse Of Dialect, 2007

Clothing does more than cover us. It reveals what we like, can afford, believe in and aspire to. Brand names influence our choice of clothes and accessories. Colours, textures, styles and cosmetics all express the image we want to project.

Sometimes we need to emphasise our allegiances or beliefs. Hairstyles may help us to stand out. Piercings, markings and tattoos can announce membership of a particular club or faith.

Do you have a tattoo? Thought of piercing your tongue? Ever dyed your hair? Do you paint your face when you go to the football or tennis?

What we eat

Lunch was different, a bit sniffier, bit of salami and odd bits and pieces inside the sangers... we were just a little bit different.Roberto D’Andrea, school boy memories, Melbourne, 1998

The food we eat does more than nourish us. It reveals what we like, believe in and where we’ve come from. Growing up, our school lunchbox can be a source of envy or shame. Later we may take pride in the food traditions of our families.

We now have more cuisines, ingredients, cooking shows and recipe books than ever before. Today it seems most of us know the difference between prosciuttoand pancetta, sushi and sashimi.

We are what we eat. Or are we?

What are you having for dinner tonight and does it say anything about your identity?