Documenting the curve

Stories from museum staff

Rapidly documenting the history of a pandemic as it happens requires museum staff to think differently about their work. Our conservators have adapted our biohazard procedures to ensure we stay safe if items we collect have COVID-19 particles on them. Our collection managers are working out how to collect and preserve online interactions in new digital formats, from Instagram posts to Zoom calls.

Together we’re all thinking through the ethics of documenting history as it happens in a way that’s sensitive to the strange and often stressful times all Victorians are living in.

Collecting contamination

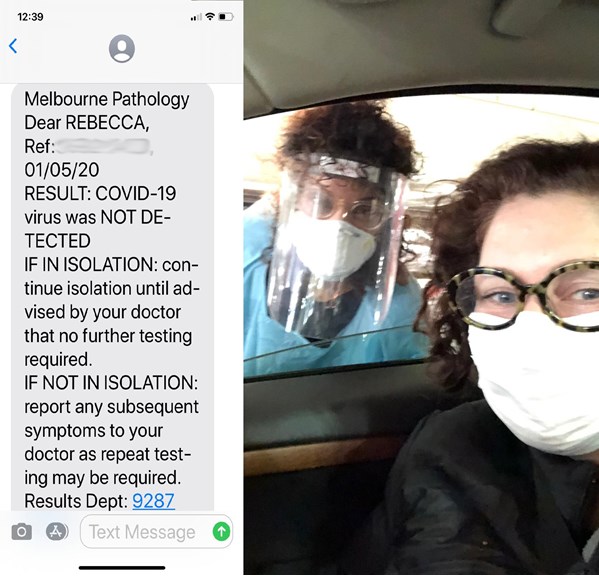

The COVID-19 virus can remain active on surfaces in trams, trains and buses, on food deliveries, and in our homes. Touching contaminated surfaces is one way people can become infected. For museum staff working to document the pandemic this adds an extra complication—the objects we’d like to collect may be contaminated with the virus.

We’re very familiar with managing hazardous materials at Museums Victoria—some of our collection items contain asbestos, poisons, pesticides and many other dangerous materials used in Victorian manufacturing, medicine and agriculture. Our scientists also have to be careful about zoonoses (diseases transmitted from animals) when they’re out in the field.

But collecting objects connected to a current and active transmissible disease poses some different problems. When objects arrive at the museum they need to go into quarantine, in the same way we isolate ourselves if we show symptoms of COVID-19. After the two-week quarantine period we need to be careful when handling objects, making sure we wear gloves and other protective equipment, to avoid re-contaminating objects as we are potentially a ‘hazardous substance’ too.

Collecting our virtual world

Social distancing has meant Victorians are living their lives online more than ever before. We’re celebrating, mourning, connecting, learning and working via Zoom, Facebook, Instagram, and countless other online platforms and tools.

Museums Victoria is collecting examples of these experiences. But, like a play, social media is a performance— your online experience is a moment in time. Even with a script, no two performances of a play are ever the same. We can easily collect and preserve images, videos or text, but capturing even an approximation of the authentic experience is hard.

Rights and permissions are another important issue for us to consider. If someone gives us permission to collect their social media story, does that give us the right to collect other people’s comments and reaction to their post? Many social media platforms also have strict terms and conditions on what can be saved and stored.

Museums Victoria looks after the state collection in perpetuity, so we need to think about how we might look after what we collect today in 100 years from now. This means we need to consider the technical specifications of the formats we collect. Web-based content is often compressed or low-resolution, because that’s best for sharing— but it’s not ideal for long-term preservation.