When is a creature extinct?

It might seem a straightforward question—but it’s not always easy to answer.

Take Melbourne’s missing dragon, for example.

For one, you have to be certain it isn’t out there, somewhere, lurking in subterranean lairs.

Which is precisely what Dr Jane Melville hopes is the case.

The Victorian grassland earless dragon hasn’t been seen for decades, the plains it called home largely ploughed and paved.

But the Museums Victoria herpetology curator holds out hope that it can not only be found—but saved.

'It’s really important to get out there and look,' Jane says.

First, though, she must travel to the U.S. capital and face the question: is it extinct?

And Jane will have to convince the world’s conservation authority of the answer: perhaps not.

Dragons are diverse

The frill neck, thorny devil, water and bearded dragon are among the better known of its Australian members of the Agamidae family of dragon lizards.

The grassland earless dragon is among the more obscure. This may be due to its secretive nature—or simply because there are so few of them left.

Until 2019 the grassland earless dragon was believed to be a single—endangered—species.

Then Jane released a paper and everything changed.

After extracting the DNA from specimens held in museums across Australia, Jane’s team proved what had been long suspected. The grassland earless dragon was not a single species, but several.

Overnight, three new dragons were born.

At the same time Jane's research raised that question about a fourth species.

'We need to look at whether the Victorian grassland earless dragon is extinct,' she says.

The question remains open, the stakes high.

'This species would be the first extinction of a reptile on mainland Australia.'Dr Jane Melville

'It is fun to name a species'

'But it's also important,' Jane says.

She would know. Over her career, this mother of dragons has named about 20. The figure climbs to 34 species when you include those which had to be revised a result.

Which was the case with the grassland earless dragon. Before 22 May 2019, the creature known to scientists as Tympanocryptis pinguicolla was believed to haunt fragments of the temperate grasslands across south-eastern Australia.

After Jane's paper, scientists had to get their tongues around two new Latin names—one for a dragon found in the grasslands of Bathurst and one of Cooma.

Another was repurposed for a dragon now found only around Canberra.

T. pinguicolla was now reserved for a dragon which historic records show once inhabited the grasslands of Melbourne.

But, since 1969, the only dragons seen in that range have been in museum vaults—specimens in jars of ethanol.

Until relatively recent, 50 years without a confirmed sighting was enough to declare a creature extinct.

Enter the ‘e’ word.

Fortunately for Melbourne’s dragon, that question has become more complicated these days.

Earless dragons are elusive

What we know of them is gleaned from fragments.

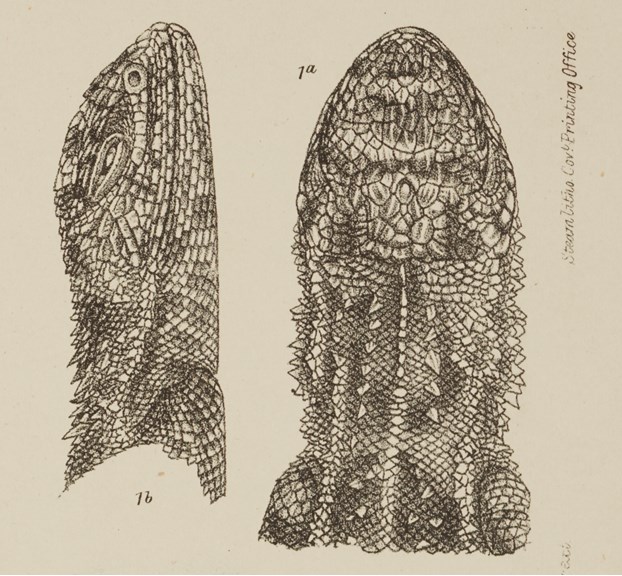

From the specimens in the museum we know the Victorian dragon was about 15cm from head to tail, light brown in colour, with three white stripes down its back and dark bands across its body.

We gather it was an energetic critter. It ate insects.

According to a 19th century naturalists’ account, the Victorian dragons were 'often met with under loose basalt boulders'.

That 1894 description had them seeking refuge in small holes, including the lairs of trapdoor spiders.

From its cousins in Canberra and Monaro, we know just how hard it would be to find—if it is still out there.

But it this precisely this quality which gives Jane hope.

'It's a very secretive lizard ... you wouldn't see it just walking around.'

There is an extinction forumula

Or a scientific method to calculate its likelihood.

There are several, in fact. In her May paper, Jane and her team used five.

With data from the museum’s record of confirmed sightings, they crunched the numbers.

The optimal linear estimator results did not augur well at all for the missing dragon. By this calculation, the species went extinct in 1994.

The Solow and the Robson & Whitlock methods were worse. Each put the dragon’s doomsday in 1993.

Strauss & Sadler had more faith in the dragons' ability to persist—but still saw them all perish by 2010.

But, using a different Solow formula, there is a chance that some dragons, somewhere, might have clung onto life.

At least a 5% chance. Not great odds, but enough.

The equations are complicated but the results distill into one word.

‘Thus,’ the paper reads, ‘results from the estimation methods as to the chance of T. pinguicolla being extinct in 2019 are equivocal.’

Another Latin word.

Equivocal.

It's #WorldLizardDay! 🦎 The Victorian grassland earless dragon hasn’t been seen for decades, the plains it called home largely ploughed and paved. @MVLizards herpetology curator Dr Jane Melville, holds out hope that it can not only be found—but saved: https://t.co/bPFxGUg6WH pic.twitter.com/KSZmaZx4h2

— Museums Victoria (@museumsvictoria) August 13, 2019

A fraction of doubt—a glimmer of hope

Then there are more recent sightings. Unconfirmed, but worth investigating.

This, the equivocation of the data and the elusiveness of the dragon make it too soon to apply the label ‘extinct’ on Melbourne’s missing dragon.

Or at least, this is what Jane will have to convince the people who do just that.

In November she will present her research to the herpetologists at the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The Washington D.C based organisation compiles the IUCN Red List, which places species in one of nine categories.

Based on Jane’s research, the IUCN will determine the conservation status of 34 species of dragons.

Each species will be assigned a label, among them: ‘least concern’, ‘critically endangered' ... 'extinct'.

They are just words. But they matter.

The case of a famous little possum shows why.

The possum that came back from the dead

Reports of Leadbeater's possum death were exaggerated. But perhaps not greatly so.

A relict species—ancient even by marsupial standards—it was declared extinct in the early 1900s.

The destruction of its towering mountain ash home went on unabated, the delicate little creature forgotten.

Then, in 1961, this 'fairy possum' was rediscovered.

It hasn't been saved—the possum remains critically endangered.

But what if it had not been prematurely declared extinct, Jane speculates.

What if conservation efforts had not have been delayed for more than half a century?

Perhaps more would have tried to find it.

Hunting for dragons

It’s been going on in earnest on the plains west of Melbourne since 2017.

Zoos Victoria is leading the hunt—and training dragon handlers in the event some are found.

If they do, an insurance population can be bred, remnant habitat protected, plans devised to save this missing species.

So, much hinges on that question.

"There is a very strict set of criteria on when a species is declared extinct," Jane says.

Among them, whether all possible habitat has been thoroughly surveyed.

For Zoos Victoria threatened species biologist Deon Gilbert, the answer to that question is live.

"Yes, there is likely to still be suitable unsurveyed habitat and we will continue to survey," he says.

'We absolutely still hold out hope in finding them.'Zoos Victoria herpetologist Deon Gilbert

Jane will have to present a compelling case to back that up.

For the sake of Victoria’s little dragon of the grasslands, it’s vital she does.

Editor's note: After missing for 54 years, the Grassland Earless Dragon was rediscovered in 2023. Jane is continuing her genetics work on the critically endangered species, in collaboration with Zoos Victoria.

Dr Melville is on a Fulbright senior scholarship at Washington University, St Louis, using Australian dragons lizards as a case study for global conservation.

Written by Joe Hinchliffe, Museums Victoria