The journey to Station Pier

Melbourne’s heritage-listed Station Pier was Victoria’s most important arrival point for migrants. Since 1854, the site has welcomed and processed millions of anxious and excited new arrivals. Today the pier represents the hopes, fears, joys and sorrows of all whose first memory of Melbourne was stepping onto its boards.

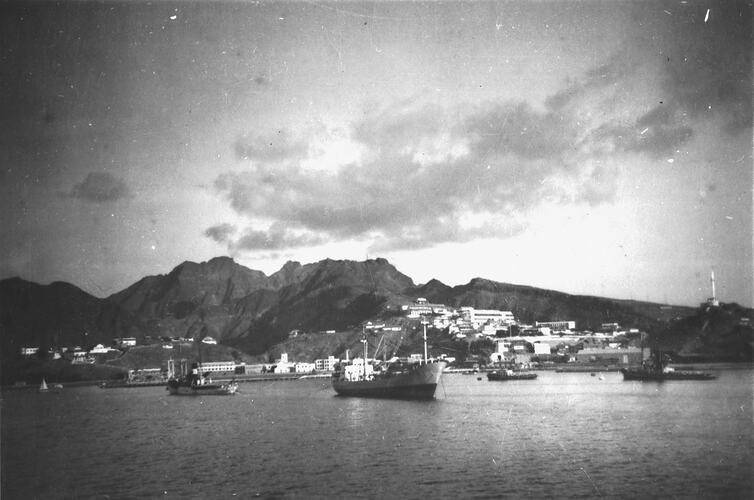

Migrant departure points overseas included various ports in the United Kingdom, western Europe and along the Mediterranean and African coasts.

“It was very affecting to see those who had friends waving handkerchiefs and weeping as they gazed at them perhaps for the last time on earth.” – Anne Gratton migrated from England in 1858

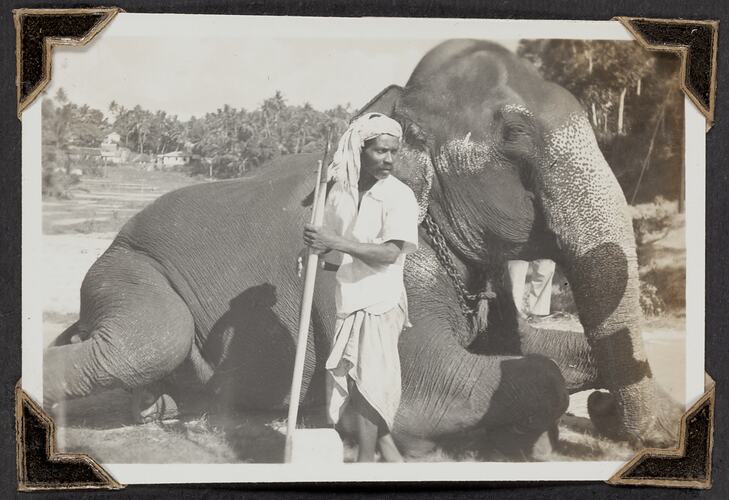

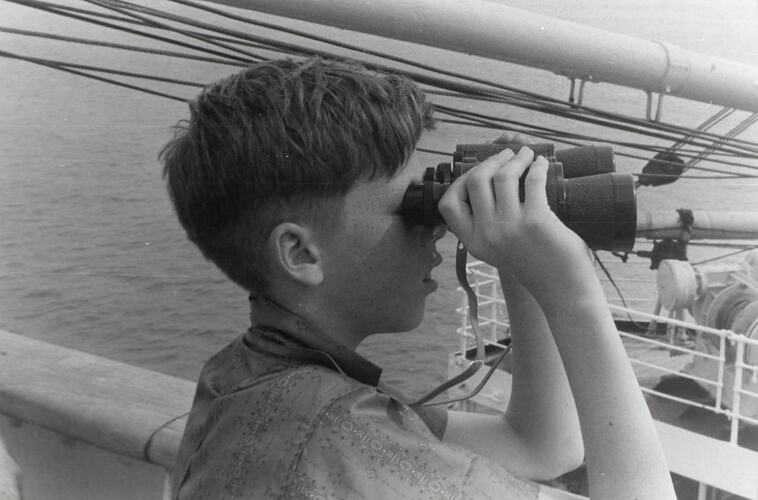

The anxiety of departure was quickly replaced by the thrill of stopover ports. Stopovers were practical necessities to restock the ship with fuel and food, and to load and unload passengers. For the migrants on board, many of whom had never travelled before, these stopovers were adventures that offered opportunities to meet the locals, bargain for souvenirs and sample a heady new mix of sights, sounds and smells.

“The excitement was a tangible thing that you could feel mounting to a fever pitch as we approached our first stop off at a foreign port. No-one knew quite what to expect.” – Leonard Rutland migrated from England in 1947.

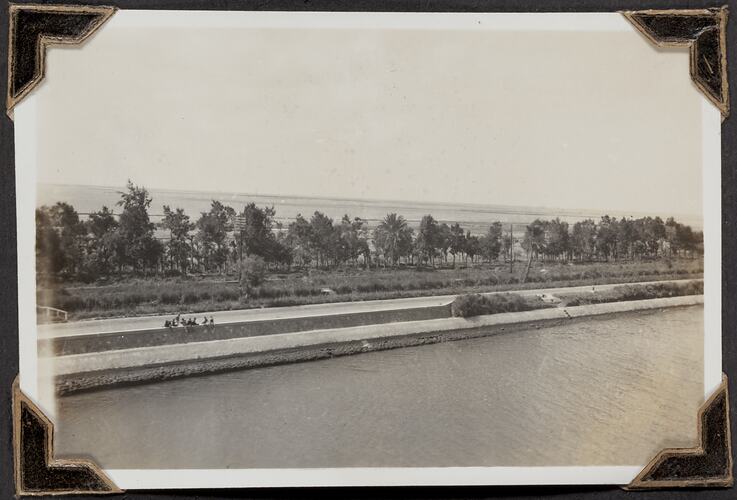

Which stopover ports were visited depended on the shipping line and the particular route taken to reach Australia. Throughout the post-war period, the most common route taken from Europe was through the Suez Canal, although access was at times dictated by political circumstances. While the canal was closed, ships took the longer route, heading around the southernmost point of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope.

After entering the Suez Canal, stopovers began with Port Said in Egypt, followed by Suez at the southern end of the canal, the former British colonial outpost of Port Aden in Yemen, Sri Lanka’s (formerly Ceylon) capital of Colombo, and the Western Australian port of Fremantle.

“We were overwhelmed at the (Colombo) wharf by an all-pervading, enveloping aroma, which we discovered once on shore to be the smell of curries from the motley array of food stalls beyond the terminal. From one of these we tasted real fresh coconut for the first time.” – Joe Vella migrated from Malta in 1955.

The aromas were pungent, the languages, landscapes and architecture were unfamiliar. Goods were unusual and exotic, providing a keepsake of visits to places that most migrants from Europe and Britain had never seen before, and would probably never see again. Buying souvenirs was an exciting part of the stopover experience.

“Looking for souvenirs was great fun. We didn’t have much money in those days, so learnt how to bargain pretty quickly.” – Steve Duane migrated from Ireland in 1963

Along the Suez Canal passengers could buy from onshore markets and the ever present street vendors or shop in the small city laneways. Many have vivid memories of the floating markets of tiny rowing boats and traditional Nile feluccas that would suddenly appear and surround the ship. Some found the vendors overly zealous in their efforts to entice the travellers to buy a trinket.

“We tried to move away from them as quickly as possible, saying 'No. No.' to every artifact they thrust at our faces.” – Frank Kriesl migrated from Hungary in 1951.

Most passengers grasped the opportunity to explore independently or organise sightseeing tours in taxis, camels or bullock-drawn carriages. Some migrants recall visits to snake charmers, local landmarks or cottage industries. But people did not have to leave the ship to encounter the wonder of new cultures, such as when a Sultan with a harem came on board:

“...we did occasionally get a glimpse of these voluptuous, exotic females, complete with ‘see-through’ harem pants, turned-up slippers, bras and yashmaks. We never saw much of the Sultan... Too exhausted, I guess?” – Leonard Rutland migrated from England in 1947.

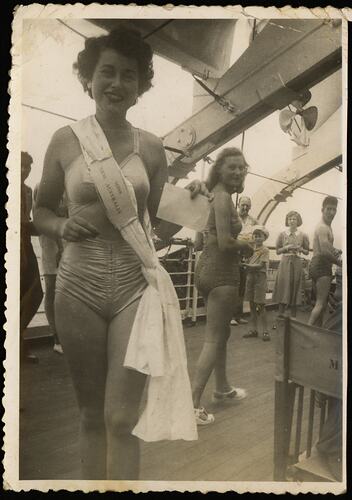

Onboard souvenir shops were installed on-board to boost revenue, offering souvenirs such as postcards, sailor dolls, ashtrays, and spoons — all sporting the ship’s name or emblem. Daily newsletters, port-of-call booklets and decorative menus were supplied; balls, parties and sporting competitions organised; and children were catered for with playrooms and organised deck games.

“The Italian crew were experts at organising people to entertain themselves. They had heaps of theatrical costumes and endless ideas about improvising. As a result we had some memorable evenings, including: Wild West night, 1920s night, Arabian night. Everyone got into the swing of it because the days were so boring.” – Robert and Maureen Hallam migrated from England in 1969.

While shipping lines and immigration officers planned and promoted a fun-filled trip, the experience could rapidly become the opposite as even the sturdiest of ships fell prey to high winds and rough seas.

“Passengers vomited anywhere, everywhere ... The corridors stank, and this added to further worsen the queasy and unsettled stomachs. The mess decks were emptied of people unable to face the smell of food. Fresh air, the easiest and best remedy was hard to come by as the waves crashed over the decks in spectacular fashion accompanied by scudding rain.” – Joe Vella migrated from Malta in 1955.

At other times the monotony of sea travel became the greatest enemy.

“For two weeks we never saw land and many passengers grew more and more restless and bored resulting in minor fights breaking out. Many deckchairs were thrown overboard.” – Connie McQuade migrated from Denmark in 1960.

The final leg of the journey was broken by a celebration on crossing the equator – a festive event that had been a maritime tradition since before 1800. It was originally an initiation rite for young sailors.

“Presently old Father Neptune made his appearance, dressed in full regalia. The crown upon his head was dazzling in its brightness, and the trident he carried was a very formidable affair.” – Thomas Park migrated from England in 1852.

By the 1900s, the festivities had become much more elaborate. Led by the crew, who painted their faces and dressed in flowing robes or grass skirts, passengers volunteered to be covered in shaving cream and ‘shaved’ with mock razors. They were then thrown in the swimming pool. Everyone received a certificate to mark the occasion.

Holding fast to long-held assumptions about what their adopted homeland might be like, the Australian coastline triggered either delight or disappointment.

“All we saw were trees and greenery and I just fell into my mother’s arms crying. We were both crying because we thought we had come to the end of the earth. There was no city in sight.” – Mariam Baker migrated from Egypt in 1966.

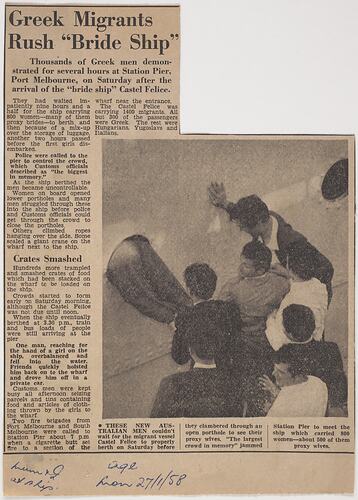

The arrival of a ship at Station Pier was a sight to behold. Streamers sailed through the air creating colourful paper webs. Teeming crowds jostled for position with friends, relatives, prospective husbands and employers waving, shouting, laughing and crying. Eager migrants leaned over the ship rails searching the crowd for loved ones while the band played anything from Waltzing Matilda to Greek music.

This emotional experience was frequently in stark contrast to the bureaucratic processes of immigration and customs. New arrivals were often guilty of bringing in items that had to be confiscated by customs.

Unfamiliar foodstuffs could be deemed contraband, suspect to a predominantly British cuisine culture. Plant seeds were a threat to the Australian natural environment so migrants sometimes smuggled things in.

“My mum knew she was doing something wrong, but she still stuffed her bra, girdle and the body cavity of my dolls with her favourite Italian vegie seeds and smuggled them in.” – Maria Attardi migrated from Italy in 1960.

From little things like vegetable seeds, olive oil or salamis, to larger household items such as carpentry tools, coffee-makers and blankets, expectations about life in Australia were reflected in what migrants brought with them.

People knew little about the distant country they were making their new home and made assumptions about climate, food and employment — sometimes correct, sometimes misinformed.

“Friends had told me that condoms couldn’t be bought in Australia, so before leaving Italy my husband and I stocked up on them. Imagine how embarrassed we were when customs opened our bags to find 750 condoms!” – Antonina Buzzotti migrated from Italy in 1969.

Finally, with belongings checked and documents in order, the migrants stepped off the pier and onto the next stage of their journey. Dressed in their Sunday best and with hearts thumping, the passengers would gather on deck to view their new home.

“When we arrived at Station Pier it was about 100 degrees, and Mum insisted I wear my full English school uniform: jumper, blazer, cap and long socks — pulled right up! I nearly passed out.” – Newsreader David Johnston migrated from England in 1953.

Also mixed with these emotions was the realisation that the welcome to Station Pier must begin with a farewell.

“Soon, the people you had made friends with while on board went their separate ways, either to meet family members or sponsors; most never to be seen again.” – Connie McQuade migrated from Denmark in 1960.

Processing a ship of 700 or more people could take all day and the job continued regardless of the weather. The pier was especially busy when, in 1949, the arrival of the Georgic attracted a crowd of 8,000! News had spread that the ship was transporting the largest number of migrants to date, a massive 2,000 people.

“Two large liners had arrived in Port Melbourne simultaneously and every man with a tray truck and a dog was down on the pier soliciting for business — transporting migrants’ luggage in those days was quite a lucrative pastime.” – Richard James migrated from England in 1954.

Migrants immediately faced the need to bargain for the transport of larger belongings and find both work and lodgings.

“I went back two years ago and I stood on the actual spot where we got off the ship, and I was starting to shake because I could remember when we got off. I had hold of the children’s hands, and I was shaking, thinking where are we going, and no idea what we were going to do.” – Maureen Hallam migrated from England in 1964.

Many people went on to stay in migrant hostels, where they could learn English and receive assistance finding work and permanent accommodation.

Station Pier: Gateway to a new life was an exhibition held at the Immigration Museum from 2004 to 2010.