The cameras that brought photography to the people

From the first consumer camera, the Kodak No 1, to the digital revolution—these are some of the most significant cameras in the history of photography, from the Museums Victoria collection.

For hundreds of years humans yearned for a way to create lasting images of the people and places of the world.

‘Photography changed the way we look at the world, it opened it up,’ says Lorenzo Iozzi, Museums Victoria’s senior collection manager of images.

‘Before photography became widespread, a lot of places in the world were just a mystery to most people.’

And nothing was more powerful in lifting the veil than putting millions of cameras into the hands of everyday people.

‘The photograph allowed people to visit remote and unfamiliar countries without the need to travel there—a luxury which was, in the main, beyond reach.

‘New inventions, new discoveries were brought into the reach of all,’ says Lorenzo.

‘The inaccessible became attainable.’

Today photographic images are everywhere, but where did it all begin?

French scientist Joseph Nicéphore Niépce was the first to crack the code in 1826, using his camera obscura to expose a bitumen-covered pewter plate.

However it took several hours to produce the image, and it would be another 60 years for photographic processes to become user friendly.

Though daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, calotypes, and glass plates came before, it was the next evolution that truly took photography to the people.

The first consumer camera

In the 1880s cameras were almost exclusively used by professionals.

That is, until the Kodak No 1 Camera came onto the scene in 1888.

Invented by George Eastman, the American entrepreneur who founded Kodak, the No 1 made use of a new invention in the world of image capture—roll film.

It was a huge technological shift from the cumbersome glass plate negative and enabled the relatively lightweight camera to be held in the hand.

Roll film is exactly what it sounds like—a roll of flexible plastic film, wound up on a spool.

Its introduction to photography allowed people to take multiple shots before changing negatives, making it much more user-friendly.

The first No 1 cameras could take 100 pictures on one roll of film, before the user sent the whole camera back to Kodak to have them developed.

‘The camera was reloaded and returned to the customer while the first roll was being processed, thereby simplifying the whole process,’ says Lorenzo.

And that ease of use became part of Eastman’s slogan: ‘You press the button, we do the rest’.

Mass production meant the cameras were relatively cheap for new technology—US$25, or about $770 in today’s money.

And the low price made photography more attainable to more people.

Kodak banked the popularity, selling more than 1.5 million No 1 cameras in the first 10 years.

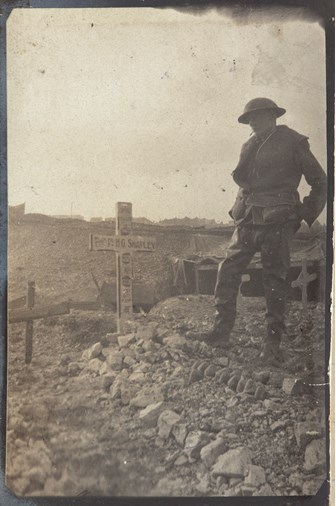

A camera for the trenches

Introduced in 1897, the Vest Pocket Kodak camera was another hugely popular model for the company.

‘Eastman’s philosophy was to bring photography to the masses,’ explains Lorenzo.

‘To do this, he knew that the camera had to be portable—almost a part of oneself (a little like our smart phone of today).

‘This landmark camera is called a Vest Pocket camera because it could just slip into a coat or vest pocket.’

And that meant people could take a camera with them more often, and to more places—including to the front during World War I.

‘It was also known as the “soldiers’ camera”, and its introduction coincided with the outbreak of the war,’ says Lorenzo.

‘Soldiers weren’t allowed to take cameras to war but many did just that, knowing the importance of photographing what they were about to witness.

‘They’d shoot a roll of film, put it in their pocket or kit bag, re-load another roll, and later mail the exposed film back home to be developed.

‘It was also a way of allowing loved ones to share their experiences on the battlefield.’

Those photos gave people back home an idea of the gritty reality of war, that was completely different to the staged photos in the late 1800s.

‘It affected how we look at the world—the moment could be more easily captured,’ says Lorenzo.

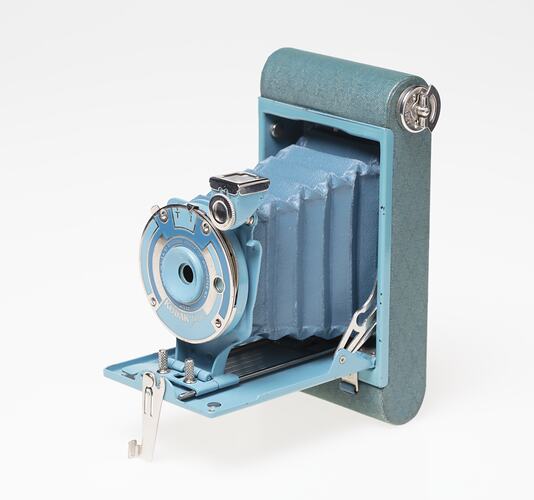

After the War, the Vest Pocket camera took on another life as the first to be sold as an accessory.

The Kodak Petite, as it was known, was exclusively marketed to women and sold with a matching lipstick and compact set.

‘The camera became a symbol of the independent woman,’ says Lorenzo.

‘The design and lifestyle that the camera embodies reflects the optimism of the time following the war years.’

It came in a distinctive art deco design with geometric shapes and a variety of colours including blue, grey, green, lavender and rose.

But while the cameras themselves were colourful, the photos they took were in black and white.

The new format

When people talk about camera roll film these days, they’re most likely referring to the 35mm format.

And the manufacturer most responsible for popularising the format is the German Leitz Cameras, now known as Leica.

But it was only through motion film cameras that the format made its way to still photography.

A landscape photographer and employee at Leitz, Oscar Barnak, started developing a lightweight, handheld camera for his own personal use in 1913.

Barnak suffered from asthma and found it difficult to carry the equipment of the day, and he turned to film camera stock for inspiration.

‘At the time, a lot of experimentation was going on into roll film as it applied to the taking of motion pictures,’ says Lorenzo.

‘Movie cameras had a vertical orientation and Leica wanted to experiment with taking images on a horizontal orientation for ease of viewing.

‘In turning the vertical batch of film horizontally, to wind up the film still by still, a totally new concept for a camera was born.’

The Leica I (the name formed from Lei-tz Ca-meras) was released in 1925.

‘It became the basis of the first 35mm camera, a format which dominated the photographic industry for over half a century and is still in use today,’ says Lorenzo.

‘The shape of many of today’s digital cameras can be traced back to the Leica.’

Even today’s advanced mirrorless cameras often use a full-frame digital sensor that is 35mm.

As Lorenzo says, it has proved to be an optimal size compromise for handling and image quality.

‘It fits in your hands, it’s portable.’

Other companies took the design further, creating the now familiar single lens reflex (SLR) camera—the first of which was the Exacta, made by German company Ihagee in 1933.

The advantage of this design is that it allows the photographer to see through the lens, via a mirror that briefly flips up when a photo is taken.

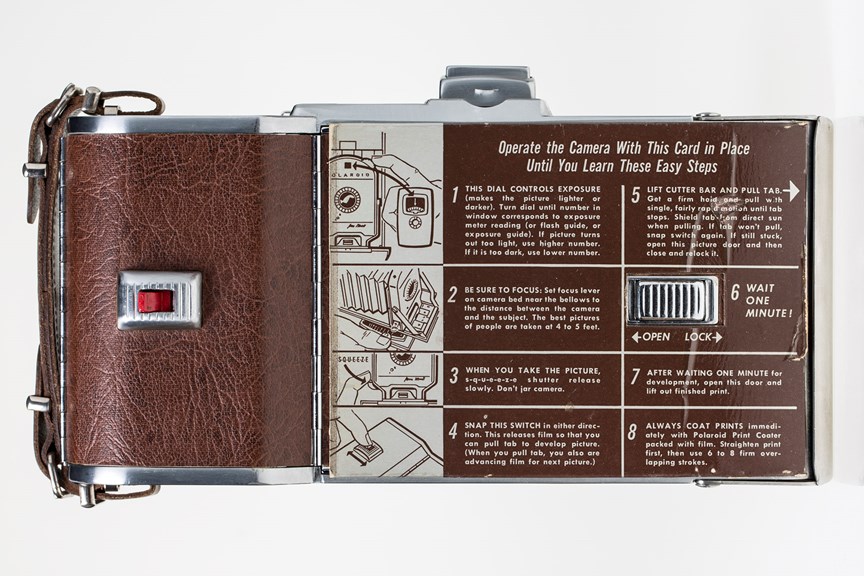

A polarising view

While we now get the instant gratification of seeing the photo we have taken within moments, nothing like that existed before World War II.

So, when American inventor Edwin Land released the first of his Polaroid instant cameras in 1948, the brand quickly became a household name.

Polaroid’s first cameras appeared to be standard for the time, but Land’s ingenious design of the film set it apart.

The camera housed two rolls of film—one negative and one positive—that were developed in camera.

The user could tear off and throw away the negative to see their freshly developed photograph just 60 seconds after taking the shot.

‘It was a big deal,’ says Lorenzo.

‘A slip of paper came first which would start the developing process inside the camera and then you’d pull out the image which would develop in front of your eyes, that was the charm of it.’

Later models, like the SX-70 released in 1972, better integrated the negative and positive film into the style of film still in use today.

‘It was definitely a forerunner to a digital image, in terms of its instantaneous nature,’ says Lorenzo.

Photography goes digital

Ironically it was the company that stood to lose the most from the technology that built the first digital camera—Kodak.

‘They actually came up with the first digital camera and they didn’t pursue it,’ says Lorenzo.

In 1975 Kodak engineer Steven Sasson was the first to create a prototype camera, complete with screen to view the images.

Even though Kodak patented the design, it was never put it into production.

In 1981 it was Japanese company Sony that released the first commercial digital camera—the Mavica.

It used a magnetic floppy disk to store the images, which could then be transferred to a computer.

But the first truly all digital camera came from Fujix (a collaboration between Fujifilm and Toshiba), in 1988.

The DS-1P, and its successor the DS-X, stored images on a memory card similar to what is still in use today (albeit much larger in size and smaller in storage capacity).

Kodak targeted professional photojournalists with its Digital Camera System (DCS) in 1991 but the price of new the technology kept digital photography out of reach of many people.

Kodak also collaborated on amateur-grade products with Apple and its short-lived QuickTake series, released in 1994.

But nothing proved more powerful in the popularity of photography, than putting a camera in an already ubiquitous object—the phone.

While professionals and enthusiasts may still use dedicated cameras, the vast majority of the photographs are produced on camera phones.

Online platforms to share images surged alongside them, taking photography to a bigger audience than ever before.

So, while Kodak’s role in the industry may have diminished its founder’s motto—‘You press the button, we do the rest’—is still alive and well in the 21st century.