Stolen Childhoods

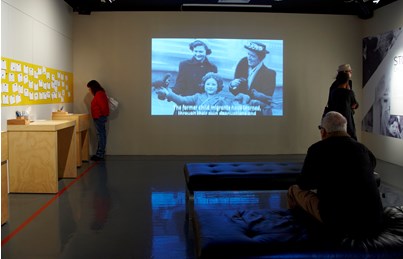

From October 2011 to May 2012, the Immigration Museum hosted On Their Own, a touring exhibition about the international history of child migration created by the National Maritime Museum of Australia and National Museums Liverpool.

The museum also developed a companion exhibition, Stolen Childhoods, to tell the story of three child migrants in Victoria and Tasmania: Hugh McGowan, Sandra Anker and Michael Harvey.

Personal stories

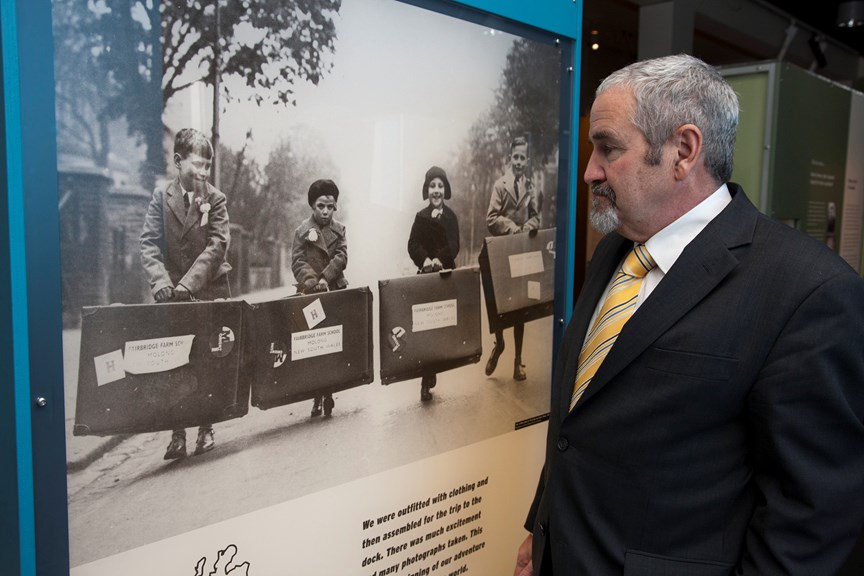

During the 19th and 20th centuries, child migration was used to promote imperial, economic, racial, social and religious goals. The people behind these agendas often ignored the fact that at the heart of all these plans were young children.

The children were separated from their families, often told lies about their parents and deported from their countries of birth. Governments in Britain and Australia failed to protect them. They were often the victims of criminal neglect and physical, sexual and emotional abuse. They were deprived of love and the stability of a caring home. Even allowing for the harsh conditions of their former lives, and the general disregard for children's welfare at the time, this treatment was inexcusable.

Some children managed to create fulfilling lives for themselves, but many more have had a lifetime of physical and emotional trauma. Their families in Britain have also suffered greatly. Apologies from the Australian and British governments in 2009 and 2010 and funds to assist family reunion have helped redress the injustices of the past, but for many it has been too late.

Here are the stories of three child migrants: Hugh McGowan, Sandra Anker and Michael Harvey.

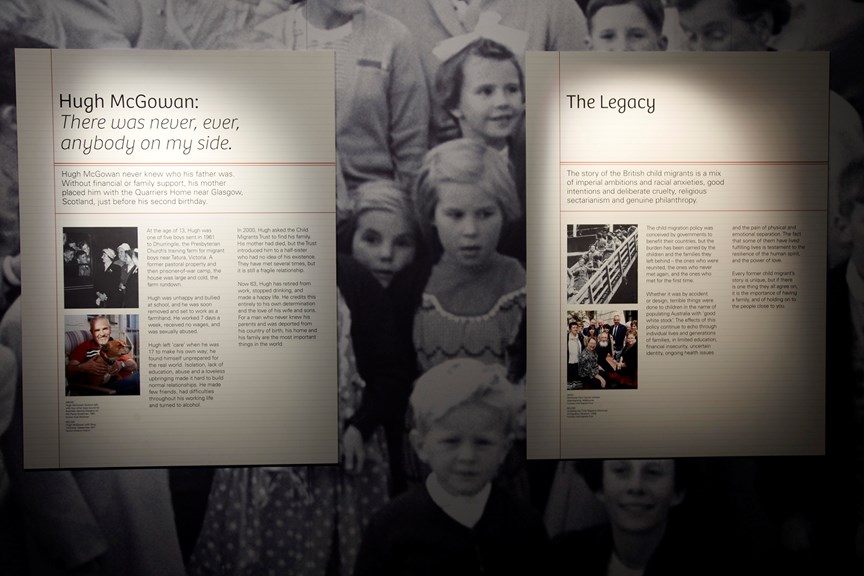

Hugh McGowan

"There was never, ever, anybody on my side."

Hugh McGowan never knew who his father was. Without financial or family support, his mother placed him with the Quarriers Home near Glasgow, Scotland, just before his second birthday.

At the age of 13, Hugh was one of five boys sent in 1961 to Dhurringile, the Presbyterian Church's training farm for migrant boys near Tatura, Victoria. A former pastoral property and then prisoner-of-war camp, the house was large and cold, the farm rundown. Hugh was unhappy and bullied at school, and he was soon removed and set to work as a farmhand. He worked 7 days a week, received no wages, and was sexually abused.

Hugh left 'care' when he was 17 to make his own way; he found himself unprepared for the real world. Isolation, lack of education, abuse and a loveless upbringing made it hard to build normal relationships. He made few friends, had difficulties throughout his working life and turned to alcohol.

In 2000, Hugh asked the Child Migrants Trust to find his family. His mother had died, but the Trust introduced him to a half-sister who had no idea of his existence. They have met several times, but it is still a fragile relationship.

Now 63, Hugh has retired from work, stopped drinking, and made a happy life. He credits this entirely to his own determination and the love of his wife and sons. For a man who never knew his parents and was deported from his country of birth, his home and his family are the most important things in the world.

Sandra Anker

"I thought there had been a terrible mistake."

Six-year-old Sandra Hill believed she was going to South Africa to live with relatives. Instead, she left the SS Asturias in Melbourne with four other children to live at Northcote Farm School in western Victoria. There had been no mistake; she was the only child of a marriage that ended before her birth, and in 1950 her guardian sent her to Australia.

Sandra lived in a group cottage with an 'auntie' and 11 other children. Even the youngest children had a heavy load of chores before and after school. Discipline was always strict, and occasionally brutal; Sandra believes her partial hearing loss was caused in 1950 when Northcote's principal hit her. Nevertheless, she settled into orphanage life, attended high school and formed friendships that continue today.

Sandra left Northcote at the age of 16 to work in Melbourne. Her inexperience and social isolation led to an early and disastrous marriage. Now re-married, she still struggles with the legacy of her upbringing, making it difficult for her to understand relationships and family life. She wonders what her life might have been if she had stayed in England.

In 1983 Sandra was contacted by her mother's relatives and in 2000 the Child Migrants Trust found her father's family, although both of her parents were deceased. For Sandra, the initial joy of finding family has developed into a complicated but hopeful relationship. Reunion has not meant the end of her story, but the start of a new one.

Michael Harvey

"My mother said, 'I want my boys home.'"

Michael Harvey and his twin brother Terry left St. Joseph's Orphanage in 1952, bound for Glenorchy, Tasmania. They grew up believing that their parents had been killed in the Blitz.

They went to live at St. John Bosco Boys' Town, run by the Salesian Order. It was a harsh place; discipline was dispensed with the Black Doctor, a length of rubber with a metal truncheon embedded in it. In such an abusive environment, the boys relied on each other for support and formed friendships that have lasted through the years.

Michael left Boys' Town when he was 14 to work as a farmhand. He speaks of this earlier life as a time of great pain, and anger that could not always be controlled. He learned to find comfort in solitude and the clean open spaces of Tasmania.

In 1994 the Child Migrants Trust found Michael and Terry's mother. She had not died in the war, but had placed the boys in the orphanage when their father deserted her. After more than 50 years, they were re-united.

It has been, in Michael's words, both a joy and a burden. He is aware of the difficulties the reunion has raised for other family members, but finding his family has given him a sense of identity and a feeling of closure. Michael's mother died in 2006; in his entire life, he spent only seven weeks with his mother, but they were the most important weeks of his life.

The legacy

The story of the British child migrants is a mix of imperial ambitions and racial anxieties, good intentions and deliberate cruelty, religious sectarianism and genuine philanthropy. The child migration policy was conceived by governments to benefit their countries, but the burden has been carried by the children and the families they left behind – the ones who were reunited, the ones who never met again, and the ones who met for the first time.

Whether it was by accident or design, terrible things were done to children in the name of populating Australia with 'good white stock'. The effects of this policy continue to echo through individual lives and generations of families, in limited education, financial insecurity, uncertain identity, ongoing health issues and the pain of physical and emotional separation.

The fact that some of them have lived fulfilling lives is testament to the resilience of the human spirit, and the power of love.

Every former child migrant's story is unique, but if there is one thing they all agree on, it is the importance of having a family, and of holding on to the people close to you.

'Forgotten Australians'

Many of the former child migrants interviewed for this exhibition object to being called 'forgotten Australians', a term used by former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in his 2009 apology to children in care. Child migrants were essentially stateless – citizens of neither Britain, their country of birth, nor Australia, the country that asked for them to come.

For many it has been a long and difficult process to win recognition as Australian citizens. They believe that the term 'forgotten Australians' indicates the Government's failure to recognise the specific experiences and difficulties of the former child migrants.

Museum Victoria appreciates the generous contributions of:

Sandra Anker

Michael Harvey

Hugh McGowan

Child Migrants Trust

International Association of Former Child Migrants and their Families

Australian National Maritime Museum

National Archives of Australia

State Library of Victoria

Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office

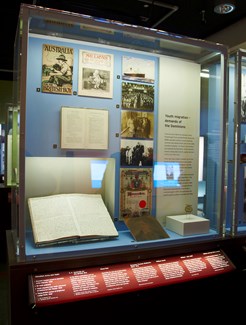

Where did the children go?

Child migration schemes were subject to very little regulation, and it is impossible to know how many children came to Australia, when they arrived or where they went.

Records were erratic and incomplete, a result of poor record-keeping, incompetence or – as a 2001 parliamentary inquiry found – fraud and criminal neglect. This is the most complete list of receiving institutions available at this time.

Western Australia

St Vincent's Orphanage, Castledare

Clontarf Boys' Town, Perth

St Mary's Agricultural School, Tardun

St Joseph's Farm & Trade School (later known as Bindoon Boys' Town), Bindoon

Nazareth House, Geraldton

St Joseph's Orphanage, Subiaco

St Vincent's Foundling Home, Subiaco

St Joseph's Home, Kellerberrin

Fairbridge Farm School, Pinjarra

Swan Homes, Perth

Padbury Boys' Farm School, Stoneville

'Seaforth' Home, Gosnells

Methodist Girls' Homes, Mofflyn

New South Wales

Dr Barnardos Farm School, Picton

Dr Barnardos Girls' Home, Burwood

'Greenwood' Dr Barnardos Boys' & Girls' Home, Normanhurst

Church of England Boys' & Girls' Home, Carlingford

Fairbridge Farm School, Molong

'Dalmar' Methodist Home for Children, Carlingford

Burnside Presbyterian Orphan Homes, Parramatta

Monte Pio Girls' Orphanage (possible), Maitland

Murray Dwyer Boys' Orphanage, Mayfield

St Brigid's Orphanage, Ryde

St John's Orphanage, Thurgoona

St Joseph's Orphanage, Kenmore (possible)

St Joseph's Girls' Orphanage, Lane Cove

St Vincent's Boys' Home, Westmead

'Melrose' United Protestant Association Home, Parramatta

Arncliffe Girls' Home, Arncliffe

Bexley Boys' Home, Bexley

Canowindra Girls' Home, Canowindra

Goulburn Boys' Home, Goulburn

Victoria

Burton Hall Training Farm, Tatura

St John's Home, Canterbury

Dhurringile Training Farm, Tatura

Methodist Home, Cheltenham

Methodist Home for Children, Wattle Park, Burwood

Nazareth House, Camberwell

Northcote Farm School, Glenmore, Bacchus Marsh

Queensland

Riverview Training Farm, Ipswich

St George's Children's Home (possible), Parkhurst

St Joseph's Children's Home, Neerkol

St Vincent's Children's Home (possible), Nudgee

Marsden Home for Boys (possible), Kallangur

South Australia

Methodist Children's Home, Magill

St Vincent de Paul's Orphanage, Goodwood

Tasmania

Clarendon Home for Children, Kingston

Hagley Farm School, Launceston

St John Bosco Boys' Town, Hobart

St Joseph's Orphanage (possible), Hobart

St Joseph's Waterton Hall (possible), Rowella

Tresca House, Exeter

Lost Innocents: Righting the Record – Report on child migration, Commonwealth of Australia, 2001