Native and introduced rats: some quick and dirty facts

A guide to the differences between, and the history of, native and introduced rats in Victoria.

Rats can get a bad rap, but it’s not all justified

When it comes to reputations, it’s fair to say that amongst mammals, rats have a tough time.

There are few animals regarded with such contempt by humans that their very name is considered an insult.

Like their mousy relatives, rats are frequently associated with disease, a lack of hygiene, general squalor and, at times, as a harbinger of death.

The best-known species from the genus Rattus are quite remarkable in a way—as ultimate survivalists, they are worthy of admiration in equal parts to the revulsion they elicit.

They have adapted so well to living in association with humanity and civilisations that they’ve become commensal animals, thriving in the detritus of human activity.

However, true rats—species of the genus Rattus—are a more diverse group of species than you might think, somewhat overshadowed by the reputation of the ‘big two’: the Black Rat, Rattus rattus, and the Brown Rat, Rattus norvegicus (aka the Ship Rat, or the Norway Rat).

Confusingly, the Black Rat rarely has black fur; more commonly it is an array of greyish–brown on the head and back and a pale, often white, belly.

More predictably, the Brown Rat’s fur is best described as being…well, brown (but also with a paler belly).

The black and the brown—the ‘big two’ and you

In Australia, and much of the world, Black Rats and Brown Rats are invasive pests and need little by way of introduction.

While they have differing origins (the Black Rat hailing from India; the Brown Rat from Siberia and China), both species have managed to spread globally, becoming well established around human habitation and animal enclosures on every continent except Antarctica.

A combination of characteristics have led to the population explosions of these two species worldwide.

Both species are fiercely competitive for their resources, have unfussy generalist diets and a capacity to breed very quickly when conditions are favourable.

As Human populations burgeoned and dispersed across the globe, it provided plenty of habitat—which in turn, spelled global success for these two species.

But what is perhaps less well known is that apart from Black Rats and Brown Rats, there are many other species in the genus Rattus that are native to Australia, and they have very different stories to tell.

Native Australian Rattus

Many people are surprised to know that there are native rodents in Australia at all.

A popular misconception is that the only native Australian mammals are marsupials (like possums, kangaroos and koalas), or monotremes (Platypus and Echidna), but this isn’t the case.

There is an extensive list of placental mammals that are native to Australia (that is, mammals that nourish their fetus via a placenta, rather than in an egg, or in a pouch).

These other native mammals include not only rodents (rats and mice), but also bats and marine mammals.

Rodents in particular have been in Australia for many millions of years—in this respect they are far more worthy of the name Australian native than species like the Dingo, for example.

There have been three ‘pulses’ of rodent incursions to continental Australia (that is, modern day Australia and New Guinea) over geological time.

The first of these ‘pulses’, 6-8 million years ago, brought in the ancestors of Australia’s so called ‘Old Endemic’ species of rodent from Tribe Hydromyini.

This includes a wide diversity of mammals with intriguing common names, like Rabbit-rats, Rock Rats, Water Rats, Stick Nest Rats, Mosaic-tailed Rats, Prehensile-tailed Rats, and Hopping Mice.

All stemmed from this Hydromyini group, with each species establishing a unique niche in Australia’s unique biomes.

These animals tell a very special story, as their ancestors crossed several oceanic barriers between Asia and New Guinea before diversifying on the Australian continent.

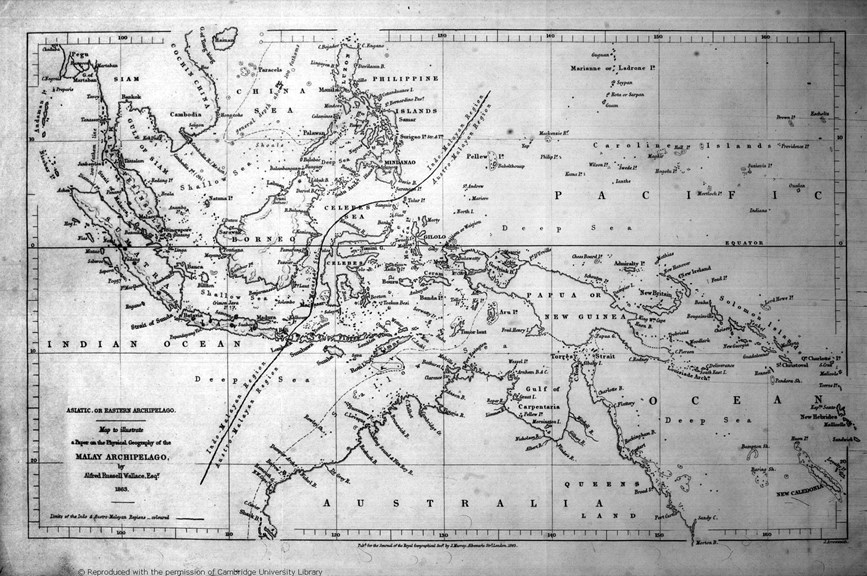

These oceanic barriers represent one of Earth's sharpest biogeographical boundaries, separating species descended from Asian ancestors in the west from the Australian origin in the east.

The most famous of these barriers is recognised as the famed ‘Wallace’s Line’, that runs through modern-day Indonesia.

Wallace’s Line, and the work of its namesake Alfred Russel Wallace, contributed enormously to evolutionary sciences.

This Wallace-straddling characteristic of rodents alone makes them of particular interest to researchers of biogeography, like Museums Victoria’s own Dr Kevin Rowe.

The second ‘pulse’ of rodents arrived around one million years ago, and is referred to as the arrival of the ‘New Endemics’.

These also crossed Wallace’s Line, and their closest relatives still live close to this boundary, in Sulawesi.

Amongst these were the first Australian Rattus species; a suite of what would become seven distinct native species of rat that adapted to life in a variety of habitats—from coastal heath, to arid desert, to lush tropical rainforest.

These are the true Australian native rats.

The final pulse is better referred to as an introduction rather than an expansion of range.

This was the unwitting introduction of both the Black Rat and the Brown Rat pest species with the arrival of European colonists in the late 1700s, along with their equally unwelcome little cousin the House Mouse, Mus musculus.

What Rat is that?

Although the ‘New Endemic’ rats of Australia have been here for a million or so years, they can at times physically look similar to their less desirable pest relatives.

In Victoria, the most abundant native Rattus species are the Bush Rat, Rattus fuscipes, and the Swamp Rat, Rattus lutreolus.

While all looking superficially similar, these species can be differentiated from the ‘big two’ by a number of features.

Firstly, these are easiest to separate from the Brown Rat because it is generally much larger.

There are no other rats found in Australia that have the same robust body, slanted snout and thick, seemingly naked tail—so this can be ruled in or out quite quickly.

Similarly the Rakali, or Water Rat, is easily differentiated by its large size, gold-tinted fur and long, white-tipped tail.

When contrasting the introduced Black Rat from our native Victorian rats, the chief features to look for are:

- The relative tail length—the Black Rat has a long tail compared to its remaining body length, so a very obviously long tail is a good clue that it is a Black Rat. Swamp Rats have a much shorter tail compared to the rest of their body.

- The shape, size and position of the ears—Black Rats have proportionally large, rounded ears that stick out proud of the rest of the skull and if folded forward, could cover their eyes. In contrast, Swamp Rat ears are rounded and small, and are flat to the skull. The Bush Rat’s ears can be larger than a Swamp Rats, but are generally still smaller than those of a Black Rat.

- Where it was found and what it was doing—this is an often overlooked aspect of rat identification but can be a a good indicator of the species. Native Rats are generally shy and skittish, and feed on native plant shoots and the like. Black Rats, by contrast, are bold. They will happily run along fence tops, clamber through trees, saunter down pathways without too much fear, and have been known to eat directly from the hands of those who mistake them for natives.

For those wanting to burrow deeper into the story of rats, there are many fascinating stories to discover.

Our very own Senior Curator of Mammals, Dr Kevin Rowe, undertakes a great deal of research that integrates fieldwork, genetics, and museum specimens.

A good overview of Dr Rowe’s research interests in rats is found one of our Discover documentaries, and a timely reminder of his research into the plight of native Rats like the Tooarrana is found here.

So, when you next spy a brown, scuttling rodent spare a moment to consider the fascinating evolutionary path its ancestors had taken before you jump up on a chair!

Can't tell your Rattus norvegicus from your Rattus fuscipes?

Ask Us for help.