An enduring favourite of children and adults alike, Bugs Alive! gets you up close to the creepy crawlies you otherwise might not be so keen on.

Giant spiders, millipedes, and praying mantises included.

‘We’ve got diversity displays, habitat displays, that show how these invertebrates live in the wild,’ says Maik Fiedel, the manager of Live Exhibits at Museums Victoria.

‘We try to bring that into the museum in a smaller version.’

But have you ever wondered what it takes to get them there?

Or where to find them in the wild?

The Melbourne Museum is the only one in Australia with a fully sustaining living component, that includes a permanent gallery of live creatures.

And like any living organism, these live displays need a larger network to support them—what you see on the surface is only the tip of the iceberg.

Underground, there is another hive of activity where a dedicated team keeps rooms full of insects and invertebrates from different environments.

‘Our living invertebrate populations at the museum are from three distinct bio-regions: tropical, temperate, and arid,’ says Maik.

‘Our tropical invertebrates make up about 75 per cent of our display species.’

Which is why, every year, when new animals are needed to boost genetic diversity of these populations, the team heads to tropical north Queensland.

Bugs on the move

Genetic diversity is important for any population of living creatures, but it is vital to prevent population collapse in captivity.

‘We want to guarantee a high quality, 365 day per year experience for the public,’ says Maik.

‘So we need to make sure our populations are stable and genetically diverse.’

In the case of the Melbourne Museum’s live animals, the best way to do this is to introduce new males and females into those breeding populations.

But that does not mean the team wanders off into the bush, collecting anything they find.

‘We only collect what we need to keep our populations at the museum viable and what we need to bring back in order to keep going for another 12 months,’ explains Maik.

Some of these animals, though, are not easy to find.

So how do they know where to look?

‘After 20 years of operating Bugs Alive we are very good in tracking down the species we need,’ says Maik.

‘We’ve got very strong relationships with private landholders in areas like the Daintree or Atherton Tablelands that give us permission to collect a certain number of animals from their land.’

But despite all the team’s knowledge and planning, it is not always straight forward.

‘Every time we come here we can expect something different,’ says Maik.

‘I’m not saying we expect new animals all the time but there are fluctuations in populations in the wild as well as captivity.

‘However, every now and then we come across something very new—even new species.’

And some are truly spectacular.

‘A few years back we were lucky enough to find Australia’s longest stick insect, the Gargantuan Stick Insect,’ recalls Maik.

‘That was a pretty exciting find.’

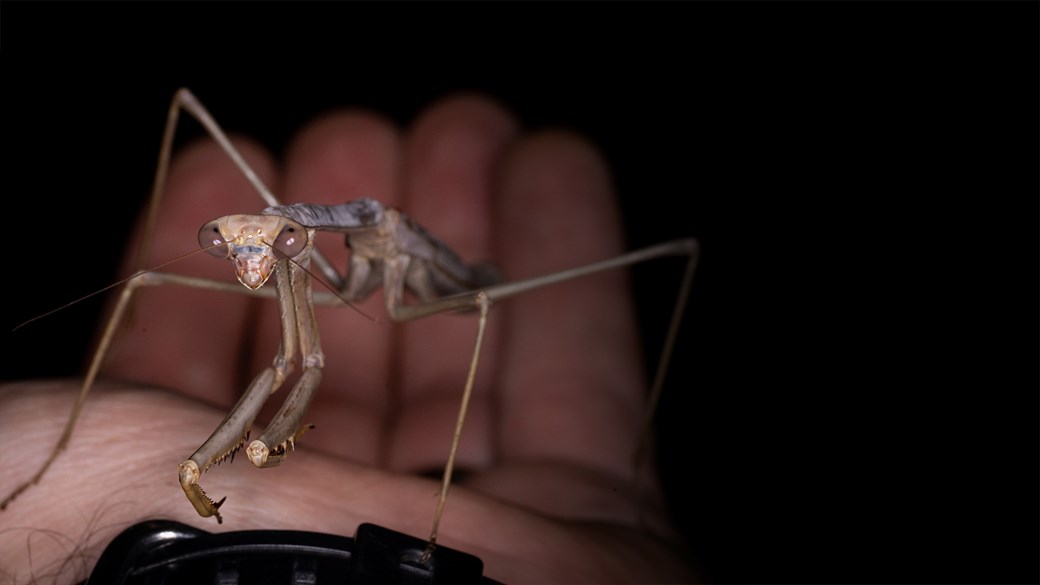

Maik’s passion for insects, particularly phasmids (stick insects) and mantids (praying mantises), has been with him since childhood.

‘I’m originally from Germany and used to be involved in the zoo industry breeding mantids and phasmids,’ he says.

‘I’ve kept that passion and brought it over here.

‘The praying mantises, they’re an alien-like creature—I’m completely fascinated by them.

‘I’ve always been curious about the way these animals blend in, use camouflage.

‘I’m particularly fond of cryptic critters.’

Hand selected bugs

‘Most of the animals we collect are actually nocturnal so that means they’re active during the night,’ explains Maik.

‘The animals come down from the canopy to the foliage and feed, so night time work is what we do.

And it does come with some challenges.

‘Especially the wet tropics—you can have a day of rain, you can have a whole week of rain; you can have a landslide,’ says Maik.

‘It’s very hard work, you can’t just take a day off and wait until the rain is gone, we’ve got a strict field work schedule.

‘If you know how to adapt and adjust, animals are still there.’

It is also labour-intensive work.

‘We don’t use any light traps, sheets, or nets—it’s all active search with head torches and containers, walking through the rainforest.’

And yes, that does mean picking animals up by hand.

Which is brave, considering some crickets can chew through wood and a finger does not present much of an obstacle.

However, armed with plastic containers to keep them in, Maik, Jo, and Tia are highly skilled at collecting these creepy crawlies quickly and safely (for all involved).

While Maik would prefer not to have to touch some animals, sometimes there is no option—like when collecting a Green Tree Ant nest.

‘They weave leaves together, they make a big nest,’ explains Maik.

‘It’s actually quite difficult to contain such a nest and bring it back to the Melbourne Museum, to Bugs Alive!'

Just one nest might hold a few million ants, all of which take issue with being touched, let alone packed into a box.

‘These animals are aggressive and react on vibrations, sounds, and movement,’ says Maik.

‘It’s challenging but over the last decade we’ve managed to find a way [to gather them] safely, swiftly.’

As Maik and the team approach a nest in the Daintree, the ants are immediately wary.

Thousands of them appear on the nest’s surface in a show of force.

In one coordinated movement, Maik cuts the branch attaching the nest to the tree as Tia collects it in a polystyrene box.

Jo pushes the lid on the box as quickly as possible.

But no matter how fast they are, arms are quickly covered in angry, biting ants, that release an acid as they attack.

‘You get a whiff of citrus in your face as a deterrent,’ says Maik.

Undeterred, Maik, Jo, and Tia secure the nest in the box and tape it closed.

Once the team is satisfied with the collection, the other bugs are packed into individual containers with food and water and air freighted overnight back to Melbourne.

And back at the museum the rest of the Live Exhibits team gets to work putting the animals in their new homes.

Some, like the green tree ant nest, go straight on display.

But there are also three separate rooms back of house in which the bugs are housed.

Each room is set up with the temperature and humidity of the region in which they were captured.

And it is here that the team care for them and manage breeding colonies to sustain the population of these animals throughout the year.

‘What we try to achieve with Bugs Alive! is taking nature closer to the public,’ says Maik.

‘It’s a snapshot of what you would find in the wild.’

And now you have some idea of what goes on behind the scenes to make that happen.