Like moths to a flame

If you read Butterflies of the night in January, you will be familiar with the moths in the photograph below.

These are Dudgeonea actinias specimens from Townsville, Queensland, bred by Frederick Parkhurst Dodd in 1902 and posted to George Lyell in Gisborne, Victoria shortly afterwards. They are amongst some of the most beautiful moths in the Lyell Collection at Museums Victoria.

As part of the research for the McCoy Seed Fund project, 'George Lyell Collection: Australian entomology past and present', one male and one female specimen have been selected for digitisation. The male specimens (on the left in the photograph above) are smaller than the females (on the right).

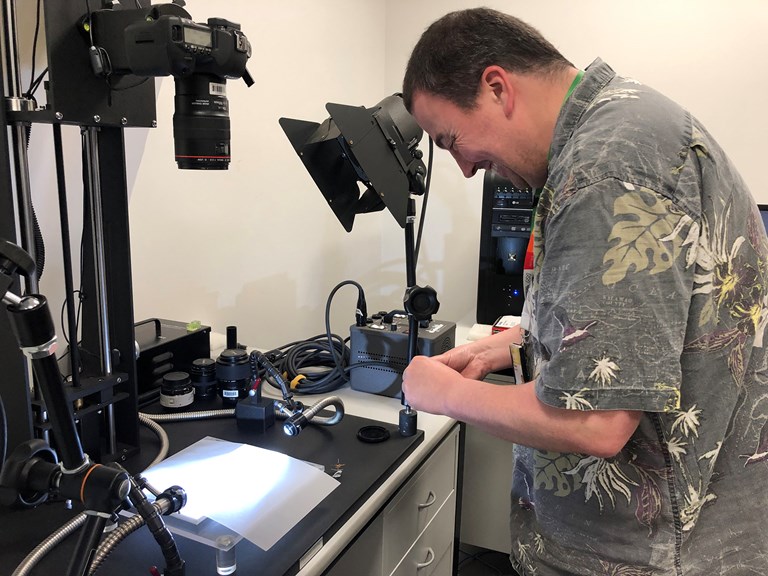

Entomologist Simon Hinkley had the painstaking task of removing the specimen from its home, the small box pictured above, and placing it on tracing paper at the base of the camera rig. In the photograph below you will note that on both sides the specimen has several lights directed at it, from above as well as from directly beside it. These multiple light sources, adjustable depending on the size of the specimen, ensure that the specimen is fully lit, with no shadows cast.

In Simon's steady hands, the specimen is carefully pinned to the tracing paper. The main lights in the room were then turned off, after which there were fourteen consecutive flashes as the specimen was photographed from the dorsal (upper side). Each photograph is tiered from the top of the pin to the lowest point on the specimen, to be compiled as one layered image.

As Nish Nizar, a colleague in the Sciences Department, zoomed in on the specimen, Simon Hinkley noted that verdigris was clearly visible around the pin (see photograph above). The Institute of Conservation (Icon) has produced an online leaflet "Care and conservation of zoological specimens" which states: "Copper and brass pins used in entomology collections can break down and react with the fats inside an insect's body. This can lead to the growth of blue-green, hair-like verdigris crystals on the pin. These can grow through the specimen, eventually breaking it apart". Whereas today’s specimens are pinned with stainless steel, copper and brass pins were used in the past. Simon advised that the verdigris generated by these older pins is a concern in the Entomology Collections. The rate of verdigris growth over time is currently being monitored by conservators at Museums Victoria.

Dodd and Lyell were great admirers of each other’s skill in preparing and pinning specimens so that they looked as perfect as possible. In their correspondence from 1897 to 1904, they exchanged information and tips about all aspects of their craft, including how to avoid the insects becoming ‘greasy’. With large moths it was important to open the abdomen and scrape out the fat within, stuffing the interiors with cotton wool or tissue paper instead before mounting and drying them. Entomologist Dr Geoff Monteith, formerly insect curator at the Queensland Museum and author of The Butterfly Man of Kuranda, Frederick Parkhurst Dodd (1991), informed Professor Deirdre Coleman, University of Melbourne and lead on the McCoy Seed Fund Project, that Dodd’s show collection of insects in Queensland were free of "greasy" complications. No doubt the challenge of preventing an insect’s fats from reacting with the older copper and brass pins was greater in smaller moths which could not be eviscerated so thoroughly.

Other risks to the collection include pests, theft, natural disaster, dissociation (labels separated from specimens), mould (higher risk in collections without temperature and relative humidity control), issues with climate control (fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity), and Napthalene crystals on specimens (when the temperature increases, Napthalene evaporates and then forms crystals when the temperature drops back).

Nish Nizar and Heath Warwick, Assistant Image Management Officer, Sciences, are working here on the final photograph (compiled of 14 layered photographs in one image. They are ensuring that the background is a clean white so that nothing detracts from viewing the specimen in detailed focus, magnified beyond the ability of the naked eye. Once post-production is complete on the layered photographs of the female and male specimens, we will share these images with you in a future blog.

Written by Nik McGrath, Archivist at Museums Victoria

If you have any questions or comments about the project, please contact Nik McGrath at [email protected].

This article originally appeared as a University of Melbourne blog post.