Kindred spirits

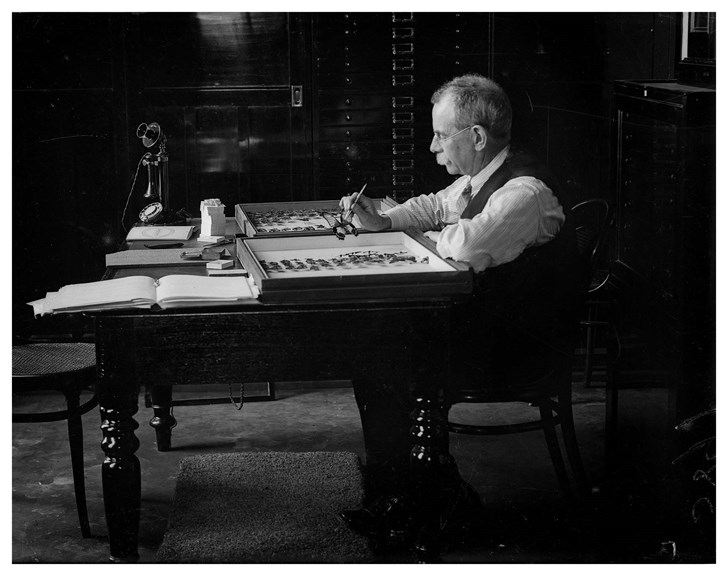

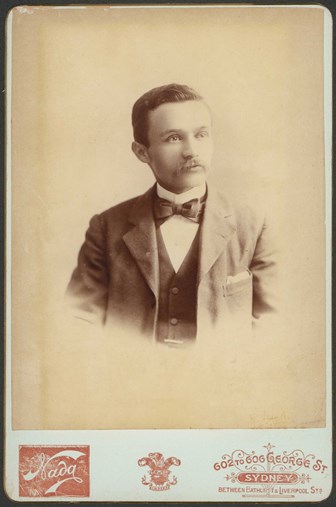

George Lyell (1866-1951) and Gustavus Athol (G.A.) Waterhouse (1877-1950) were close friends and colleagues. A passion for moths and butterflies, a fastidious work ethic, and similar sensibilities connected the men from the start, evident in their letters in the Museums Victoria Archives. Between 1891 and 1947 they wrote to each other sometimes daily, sometimes weekly, sometimes less regularly, but always keeping in touch. Museums Victoria Archives hold Lyell’s inwards correspondence, including 413 letters received from Waterhouse. Lyell also kept copies of his outward correspondence from 1928 to 1930, a period during which he sent 43 letters to Waterhouse. The two men passed away within a year of each other.

We are fortunate that Lyell lived in Gisborne, Victoria, and Waterhouse lived in Sydney, New South Wales, meaning that much of their relationship, including their collaboration on The Butterflies of Australia (Sydney, 1914), is documented. Lyell’s letters to Waterhouse often remarked on the weather, not for small talk but to note the suitability of the weather for field excursions and collecting. For instance, in a letter dated 18 May 1928, Lyell exclaims: “Have had a little snow and the last week has been bitterly cold – so no likelihood of anything more on the wing except an odd Noctuid” (Oldersystem~03034, Museums Victoria Archives). Both men were well-established as collectors before they started corresponding. Waterhouse began his butterfly collection in 1893, and Lyell a few years earlier in 1888.

Sadly Waterhouse destroyed much of Lyell’s correspondence. In a letter dated 15 September 1928 we read: “I have destroyed some thousands of letters after of course entering the important notes on my cards.” This means that the story of the relationship between the two men is mostly told in the voice of Waterhouse. On a more positive note, the information Waterhouse received from Lyell, and which was used in the writing of The Butterflies of Australia was documented on index cards. These are held in the Museums Victoria Archives (Oldersystem~03037, Museums Victoria Archives).

Lyell and Waterhouse visited each other whenever they could. When Waterhouse was in Melbourne for business, he would try to make a special trip to Gisborne, often staying over for a weekend. Waterhouse wrote to Lyell on 15 September 1926 from Grosvenor Hotel, Adelaide: “arriving Melbourne 10am Wednesday 22 September… catch the 12:45 train for Gisborne … If weather good I would suggest we drive to Macedon on Thursday, as my wife wants to see the flowers &c if possible. We want to get back to Melbourne on Saturday evening. Sunday we can more or less rest, I have to see Kershaw again…” (OLDERSYSTEM~03031, Museums Victoria Archives). Kershaw is James Andrew Kershaw, curator at that time at the National Museum of Victoria’s zoological collection. The warmth of their relationship can be seen in Lyell’s note to Waterhouse on 17 January 1928, hoping that he would visit Gisborne following his trip to Hobart: “I want to have a yarn with you and should be very disappointed if you did not manage to come up” (Oldersystem~03034, Museums Victoria Archives).

Lyell often went to Sydney at Easter to stay with Waterhouse and his family. Waterhouse wrote to Lyell on 21 February 1903: “I have received your letter and am very glad to hear that you are coming over at Easter but am sorry that Easter is so late this year but you will probably get some few moths” (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives). Spending Easter together was a tradition for the friends: “What about Easter? Are you coming over? We expect you to stay with us. Going this year to the Biological Survey Cottage in the National Park from Thursday pm to Monday pm or perhaps early Tuesday morning”, wrote Warehouse on 23 March 1925 (OLDERSYSTEM~03031, Museums Victoria Archives). In a letter dated 21 March 1928, Lyell wrote to Waterhouse: “It was only this afternoon that we definitely decided I should make my usual Easter trip to Sydney” (Oldersystem~03034, Museums Victoria Archives).

Early in their correspondence, the two men addressed each other quite formally. In a letter Waterhouse wrote to Lyell on 19 January 1897, we read: “In speaking to Mr. Rainbow today he mentioned you were anxious to exchange butterflies, so I therefore take the liberty of writing to you to see if you are willing to do so” (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives). Rainbow was the Entomologist at the Australian Museum from 1895 until his death in 1919. Since Waterhouse was a regular visitor to the Australian Museum from his school days, and well respected in entomological circles, he took up the position of honorary entomologist when Rainbow died. Later he became a long-standing trustee of the Museum, from 1926 until 1947. Both Lyell and Waterhouse had extensive networks with fellow collectors and entomologists both within Australia and overseas.

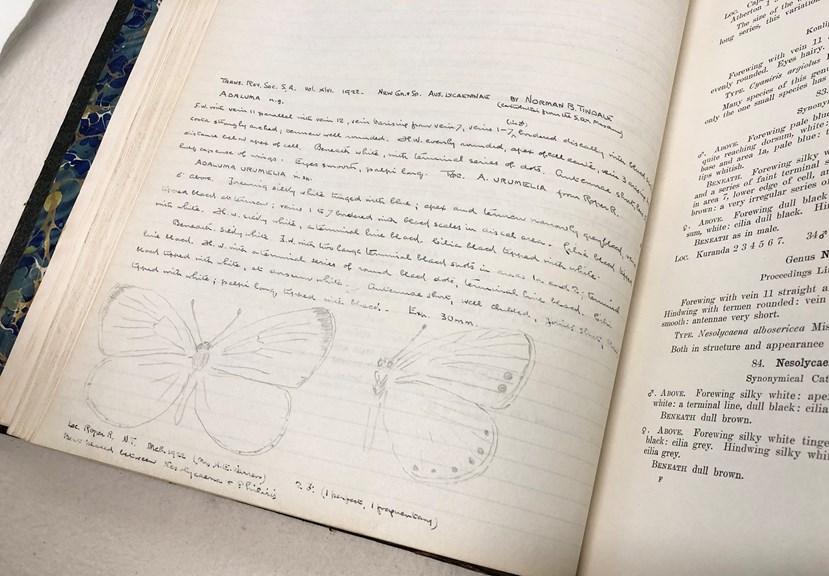

In 1914 Butterflies of Australia was published, a book co-authored by Waterhouse and Lyell. It was the achievement of a quarter century of collecting, and at least two years of solid work assembling the text and the plates. Waterhouse was the contact with the publishers, but he consulted Lyell on every point, right down to the format for specimen captions. In a letter to Lyell dated 4 September 1913 Waterhouse wrote: “Your letter of 2 just to hand. I am sorry you have so much to do. I am not wanting to rush you, but I want to get the larger groups finally settled whilst I am on them. I can see oceans of work ahead for myself in getting the neurations structural points drawn & so if I can get all the larger groups finished as soon as possible & leave you to go ahead slowly with the plate localities & dates (therefore I would like your opinion as to what method we will use for plate names) i.e.

550 ♂ Troides priamus pronomous Gray

T. priamus pronomous Gray

550 ♂ Troidea pronomous Gray (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives).”

At the time of drafting the book’s manuscript, Waterhouse did not know how to use a typewriter, so he would send sections to Lyell to type up. “It will be better I think if you have time to get the paper typed, for it is much easier to see how it goes when in type & probably it will require one further typing”, wrote Waterhouse on 9 February 1914 (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives). Years later Waterhouse learned to use a typewriter, sending typed letters to Lyell in order to build up his skills. He made many errors, endearing to behold, especially from someone as fastidious as Waterhouse. Lyell often typed his letters on Cherry & Sons business letterhead, the company he worked for and later managed from 1890 onwards. Lyell’s ready access and experience in using a typewriter was an asset when writing their book.

Although Waterhouse could not use a typewriter in the early days of their collaboration, he did learn to drive, eager as he was to collect butterflies in localities difficult to reach by train. In a letter dated 23 October 1913, he writes: “A good deal of my time at Woodford was spent in learning to drive the motor car. Today I went 30 miles, part of the time with the Constable at Katoomba for the test, which I have passed so I am now licensed to drive in NS Wales. This will be very useful as they propose having a second smaller car at Woodford & I will be able to reach spots without fatigue & not be dependent on trains” (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives).

Waterhouse and Lyell worked tirelessly on the book throughout 1913. In the same year Waterhouse’s twin sons were born, momentarily delaying their work. Waterhouse wrote to Lyell on 1 December 1913: “You know that we have always wished to have a son, though until the beginning of this year that blessing seemed to me to be impossible. However we are proud in the fact that we possess two such blessings for on Saturday evening we had born to us two fine little fellows, whom I hope are destined to play no mean part in the world. Owing to very careful attention during the last two months at least, my wife was in such perfect physical condition that everything went speedily & well & even though she is naturally somewhat excited at the possession of two boys she is well & contented. This to a certain extent will explain why I have not been able to work at the book as consistently as possible. However all the MSS is ready with the exception of Lycaenidae and Introduction &c. I looked a fair amount of MSS material out yesterday & will try & post it to you tomorrow…” (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives).

“I had a good offer the other day about our coloured plates an entomological artist was here with nothing to do for a bit & was willing to do them, so I am rather glad that the rarities will not be at the mercy of the process man. I have just seen the first plate & it is a real beauty”, wrote Waterhouse to Lyell on 3 February 1914 (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives). Waterhouse was very much pleased with the colour plates. A day later, on 4 February 1914, he added: “Coloured plate no. 1 is glorious, magnificent drawings, just showed it to McCulloch who was delighted with it. A few minor alterations have been made” (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives).

Although Waterhouse and Lyell had to overcome distance between them in order to write the book, they produced a text that was well received amongst entomologists. Lyell was concerned about collaborating at a distance, but Waterhouse reassured him on 28 March 1914: “Of course we are a little at a disadvantage being so far apart, but I think we have managed to get together a very good looking specimen of printing. A & R [Angus and Robertson] are very pleased with it, and everyone thinks it excellent, only suggesting alterations according to their own pet fancies” (OLDERSYSTEM~03030, Museums Victoria Archives).

Following the publication, Angus and Robertson sent royalty cheques to Waterhouse, and Waterhouse would then send on Lyell’s share: “A & R account for book came along the other day. I enclose cheque for your share. I have sent along receipt. You can let me have the account when I come over”, wrote Waterhouse on 12 August 1926 (OLDERSYSTEM~03031, Museums Victoria Archives). In a letter dated 21 March 1928, Lyell wrote to Waterhouse: “Thanks for the cheque for £3 10s ex Angus & Robertson” (Oldersystem~03034, Museums Victoria Archives).

Waterhouse and Lyell were forever making notes of corrections in their letters. Lyell recorded these annotations in a bound publication of the book held in the Rare Book Collection at Museums Victoria Library. This copy, which contains pages for notes, records errata as follows: “Found a mistake in the butterfly book. The female figure of chrysotricha No 776 (I think) is really donnysa. I noticed it when I put your specimen in the cabinet the other day. At that time we did not know donnysa from WA and this sex is hard to tell. I also found one in my lot of chrysotricha - you should look through yours” - wrote Waterhouse on 22 December 1930 (OLDERSYSTEM~03031, Museums Victoria Archives).

Although the two men had mutually agreed that the survivor would receive “the specimens used as illustrations in ‘The Butterflies of Australia’, together with one hundred selected specimens”, Waterhouse changed his mind. Instead, he wanted everything associated with the collaboration to go to the Australian Museum. He explained his reasoning to Lyell: “There will always be an entomologist there; at present they have Musgrave, and two assistants. Also as a Trustee, during my lifetime I will be able to help form the Entomological policy of the Museum”. On 25 May 1928 Waterhouse wrote to Lyell: “I am suggesting that we deposit the originals, negatives & blocks of the butterfly plates at the Australian Museum. Anderson has agreed to store them there & of course make them available to us at any time we want. I spoke to George Robertson about it & he was agreeable, so it only wants your consent – then I will write to A&R & get their permission in writing” (OLDERSYSTEM~03031, Museums Victoria Archives). In a letter dated 5 June 1928, Lyell protested: “There was really no need to seek my permission as to depositing originals, negatives and blocks of the Butterfly plates with the Australian Museum” (Oldersystem~03034, Museums Victoria Archives). Although Waterhouse wanted to deposit all material relating to the book with the Australian Museum, the Archives team at the Australian Museum confirm that Lyell kept hold of the manuscript, proofs, and index cards. These were eventually donated to the National Museum of Victoria following Lyell’s death.

On 24 August 1929 Waterhouse wrote again to Lyell, informing him of his intention to leave even more of his collections and research materials with the Australian Museum, the institution which he regarded as best placed for the donation. Of the State Museums, the Australian Museum was in his eyes “the largest and best endowed”, and he had decided that it was “of the first importance for science that the whole of the specimens used in “The Butterflies of Australia” should be in one place”. “I have tentatively approached the Australian Museum with the offer of my butterfly collection, together with what books I possess that are not in their library, and any necessary gear, provided they supply me with a room in which I can work at the collection from time to time and would require a free hand for the disposal of my present and future duplicates. . . . I cannot of course give my portion of the types to the Australian Museum without your permission. I have consulted Nicholson and Goldfinch as to the best Museum. I think you had already agreed that the illustrations, negatives etc. should be given to the Australian Museum for safe custody and use by any Lepidopterist requiring to use them. Let me know as soon as possible your views on the matter” (OLDERSYSTEM~03031, Museums Victoria Archives). Lyell evidently agreed, as on 30 August 1929, Waterhouse wrote: “I am very glad of your permission to hand over anything I now have that was used in “The Butterflies of Australia” to the Australian Museum. When the matter becomes more definite, I will let you know the details. My idea was something as follows: to give them my whole collection and necessary gear, and any books that are in my possession and are not already in the Museum Library, keeping only at home the big Turner Cabinet as a show cabinet, and the necessary collecting breeding and setting gear. In return, they would provide me with a room to work in, two extra cabinets, and shelves and necessary equipment”.

It was magnanimous of Lyell to agree to this donation, but Waterhouse was well aware that Cherry & Sons was not doing well in the years leading up to what we now know as the Great Depression of the 1930s. In a letter of April 23rd 1928, Lyell confesses to the anxious time ahead of him as he and others involved in the running of the company decided whether or not “it will still carry on as of old”. Throughout the following months, with the company in debt, Lyell reported that he had been caught up in “stormy shareholders meetings”, from which there emerged “a promising scheme of reconstruction”. Employees were shed and the company went into receivership until the losses were covered, all of which meant that Lyell could not charge to the business his Easter visits to Sydney. With his friend’s financial problems uppermost in his mind, Waterhouse wrote to Lyell suggesting that the Australian Museum would buy his share of the Butterflies of Australia specimens. He advised Lyell to make the suggestion himself, reassuring him at the same time that such an overture “would not in the slightest affect your standing, for the Museum bought the Hargraves collection of shells and afterwards elected him a Trustee of the Museum. Carter has also sold part of his collection to the National Museum, Melbourne, and Froggatt his to Canberra”. In other words, there was nothing un-gentlemanly or demeaning about selling one’s research collections. The chief objective was, he reiterated, to serve science: “The great point I want to emphasise is that the whole of the specimens in connection with “The Butterflies of Australia” should be in one Institution, so that they would at any future time be available to scientific workers. (OLDERSYSTEM~03031, Museums Victoria Archives).

If you live in Melbourne and find this story intriguing, come along to Nocturnal at Melbourne Museum on Friday 4 October between 7pm and 9pm to meet Prof Deirdre Coleman (University of Melbourne), Simon Hinkley (Entomologist), Hayley Webster (Manager Library), Mark Nikolic (Legacy Registration Officer, Sciences Collections) and Nik McGrath (Archivist) and to see items from the George Lyell Collection, including moths, butterflies, letters, photographs, and Butterflies of Australia from Museums Victoria State Collection, Museums Victoria Archives and Museums Victoria Library Rare Book Collection.

The George Lyell Collection: Australian Entomology Past and Present McCoy Seed Funding Project is led by Professor Deirdre Coleman, School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne. Nik McGrath, Archivist, Museums Victoria, is the coordinator at Museums Victoria, with colleague Simon Hinkley, Collection Manager, Entomology and Arachnology.

Written by Nik McGrath, archivist, Museums Victoria, and Professor Deirdre Coleman, University of Melbourne

If you’re interested in learning more about the project, see previous stories Butterflies of the night, Like moths to a flame, Pressed orchids, The sting of the final letter, and Light sheets.