Isabel Cookson: one tough ‘Cookie’

One of Australia’s first professional female scientists, Isabel Cookson was a ground-breaking palaeobotanist whose work continues to inspire the next generation.

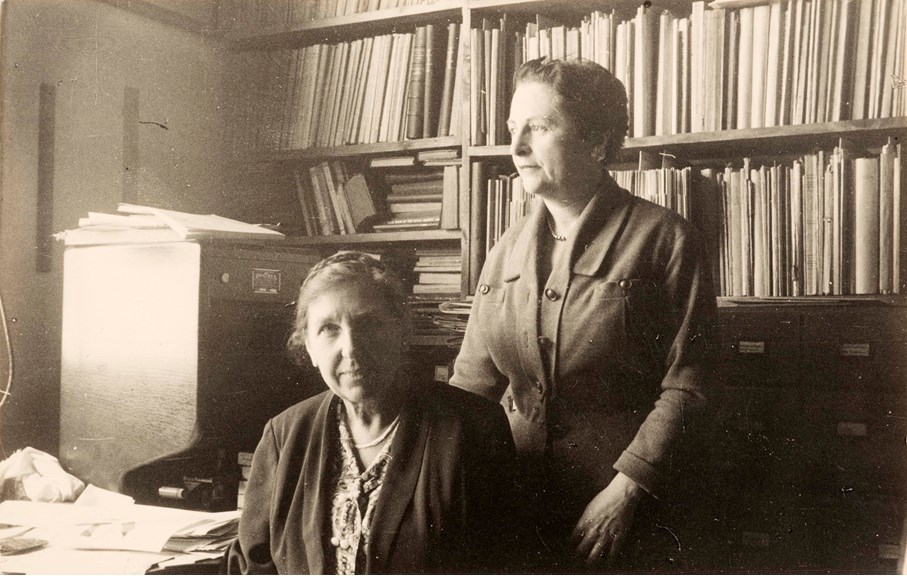

Unearthing the stories of pioneering women from the Museums Victoria Archives.

Dr Isabel Clifton Cookson, or ‘Cookie’ to her friends, was a pioneering palaeontologist of the 20th century but her greatest contribution to the field was in fossil plants.

Isabel displayed an early affinity for natural sciences—something that served her well in her 58-year scientific career spanning multiple disciplines—but it was not easy.

She overcame multiple professional and personal obstacles in her pursuit of a scientific career, including the death of her father while she was in high school.

By age 22, she graduated with first class honours in biology and zoology from the University of Melbourne and was elected as an associate member of the Royal Society of Victoria.

‘Without doubt it illustrates Isabel’s desire to immerse herself within scientific discourse,’ says Bec Carland, senior history curator at Museums Victoria.

Isabel’s first professional position was as a research student at the National Museum of Victoria (now Museums Victoria) under palaeontologist, Frederick Chapman.

Up until this point all her botany studies had been on modern day plants, but it was at the museum that she first became acquainted with fossil plants.

Isabel catalogued the ‘Sweet’ collection of fossil plants from Leigh Creek, South Australia, and investigated the museum’s collection of Palaeozoic plant fossils.

She described two specimens, but they belonged to a genus so far only found in the northern hemisphere.

To identify other specimens in the museum’s collection, Isabel needed to consult palaeobotanists in England and made the long sea voyage in 1925—the first of many working trips to the UK.

International acclaim

At the University of Manchester Isabel met Professor William Lang, who would become a long-time mentor and collaborator.

He urged her to return with more fossil plant material from Australia and even arranged a job for her at the university.

The following year Isabel returned to Manchester with specimens from the museum’s collection and some she had collected herself near the Yarra Valley, northeast of Melbourne.

Among these were more than 400-million-year-old, Silurian-aged fossils that would come to be known as Baragwanathia—at the time the oldest known vascular plant in the world.

For eight years, the pair collaborated on several scientific publications that revolutionised the understanding of how early plants evolved—and not just in Australia.

On a trip to Perton Quarry, in England’s west, Isabel found three specimens of a small, fossilised plant in sandstone.

When describing these plants William Lang named the genus after her.

‘I propose the name Cooksonia in recognition not only of Dr Isabel Cookson having collected the type specimens…but also of her important work on plants of still earlier geological age from Australia,’ he wrote.

One of Australia’s first professional female scientists

While Isabel had become internationally renowned for her expertise as a palaeobotanist, it wasn’t until 1929 that she secured her first full-time job.

She was appointed a permanent lecturer at the University of Melbourne’s new biology department—making her one of the first women to become a professional scientist in Australia.

Despite her expertise, at the time women were paid about half the salary of men for the same job.

‘Academic tenure and promotion evaded so many amazing women in the 20s, like Isabel and her mentor Ethel McLennan, who were passed up for male colleagues,’ says Bec.

Isabel held the position for 17 years, while continuing to publish scientific papers on the development of primitive plant life.

In the 1940s Isabel began studying fossils of plants and fungi from the Latrobe Valley’s brown coal mines, in eastern Victoria.

But it was her discovery of pollen in the fossils that led Isabel to become Australia’s first palynologist.

Isabel was one of the earliest palynologists to recognise pollen and spores could be used to reliably define different geological periods, and areas for oil exploration.

The University of Melbourne even established the Pollen Research Unit under her leadership in 1949.

Within three years the university promoted Isabel to research fellow and, finally at age 58, she earned a comfortable salary.

‘Retirement’

Because she had no pension rights, Isabel’s retirement in 1959 was entirely self-funded.

Not one to sit idle, Isabel continued to collaborate with international scientists and publish her findings—in fact, she published about a third of her total 93 papers after retirement.

Tom Darragh, curator emeritus at Museums Victoria, first met Isabel in 1960 when she was an honorary associate of the museum.

He remembers her as a dedicated scientist even in later life.

‘People probably thought of her an as eccentric, but I don’t think she was, she was just immersed in what she was doing and wanted to keep doing it.

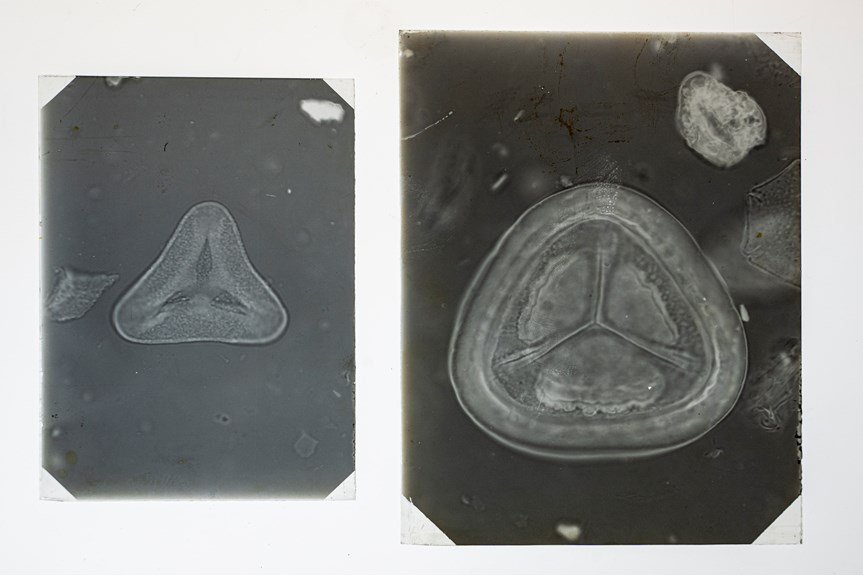

‘I can remember her photographic setup, which was incredibly old fashioned, but she produced beautiful results—really good images on glass plates,’ says Tom.

Isabel had a hand in describing more than 550 species and 110 genera of plants and palynomorphs.

Even now, decades later, her substantial legacy is still guiding modern day palaeobotanists.

One of them is Fearghus McSweeney who was the first to discover Cooksonia, the genus of fossil plant named after Isabel, in Victoria.

‘Even though they were found all around the world, none were found here in Australia, this is the first one that’s been described from Australia,’ says Fearghus.

‘And what’s even more amazing, is that it was in an area that Isabel Cookson had worked on in 1935, so there was a bit of symmetry about it in that it was one of her own.’

It now sits alongside Isabel’s own collection, that she donated to Museums Victoria.