Glowing animals: understanding bioluminescence and biofluorescence

What do platypus, dragonfish and scorpions have in common? They’re all animals that can glow in the dark.

Glowing animals are truly fascinating, and amongst nature’s more bizarre and beautiful oddities.

Humans have harnessed the use of glow-in-the-dark substances since the 1600s, more recently in luminescent watch dials and glow sticks, but nature has been putting on a far more spectacular and nuanced light show under the cover of darkness for millions of years.

Hundreds of animals have independently evolved these traits for very different purposes—some for communication or camouflage, others to attract prey or dissuade would-be predators, and some reasons we are yet to fully understand.

But how do they do it?

You Can Glow Your Own Way

Living things that produce light usually do so via one of two ways—bioluminescence or biofluorescence.

Bioluminescence (from the Latin lumen, meaning light) is the process of generating light from a chemical reaction (involving two molecules: luciferin a substrate, and luciferase an enzyme) inside the bodies of some animals and plants.

The important distinction is that this occurs without the influence of external light sources, like sunlight, and doesn’t generate heat.

Biofluorescence on the other hand, happens when organisms absorb sunlight and transform it—emitting the light as a different frequency or colour (usually green, orange, or red).

No matter the way animals put on a glow, the results can be astonishing and even mesmerising—no coincidence given it’s often the desired result for animals like the anglerfish, which uses its light to lure in prey.

There are other deep-sea fish that use light to hunt in a slightly more creative, and terrifying, way.

Dragonfish have light-emitting organs, called photophores, on their cheeks.

The thing about these predators is that they make use of a rare trait in the deep sea—they can see red.

Red light has the longest wavelength of the visible spectrum and doesn’t penetrate more than 100 metres below the surface.

It’s for this reason that many deep-sea creatures are red themselves because it makes them effectively invisible to most other predators.

But that doesn’t work on the dragonfish.

Its bioluminescent organs emit red light, which only they can see, giving them quite an unfair advantage over their hapless prey.

So, what can other creatures do to defend against this?

In the ocean, light may penetrate from the surface, so some marine species use an array of light-emitting organs on their bellies to hide their silhouette from predators lurking below, known as counterillumination.

Animals like the Southern Bobtail Squid can even change the intensity of their in-built light to match different conditions.

But that only works when there’s enough light from above.

In the deep sea, some shrimp use their own bioluminescence to ‘vomit light’ and blind predators.

Other animals, like the Banded Brittle Star, take a more drastic approach.

They can drop off the ends of their arms, which have a green bioluminescent glow, as a decoy for predators.

Fluorescent findings

Underwater organisms are well known to make use of both methods of light production.

However, we are still learning about these processes and which animals use them.

While examining biofluorescent corals in 2015, American Museum of Natural History researchers observed something entirely unexpected.

A passing Hawksbill Turtle appeared like a ‘bright red and green spaceship’ under specialised blue lighting.

This glow may be partially enhanced or caused by algae but as yet, scientists don’t entirely understand how or why this happens.

In fact, it has only been in recent years that humans have discovered just how many creatures glow in the dark.

Scientists have observed biofluorescence in a species of Argentinean frog, and the Virginia Opossum from North America.

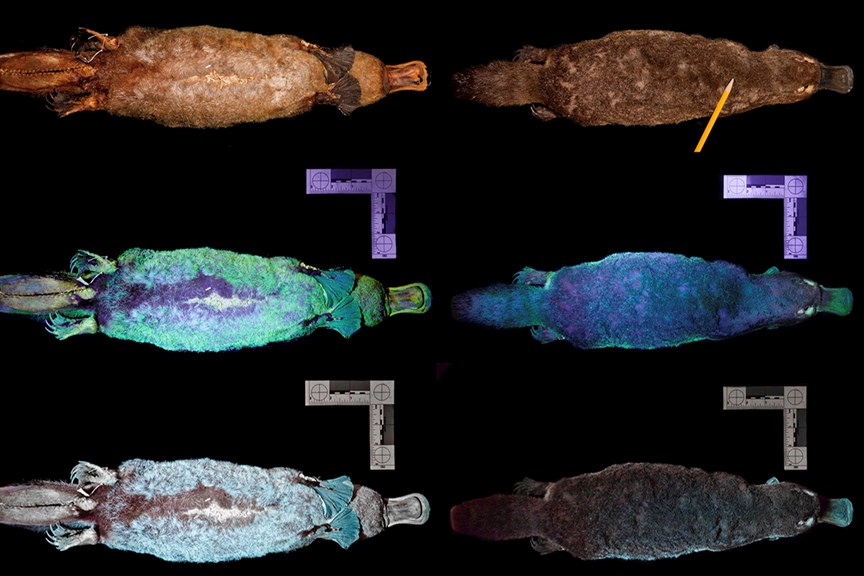

Back home in Australia, mammals and marsupials like the platypus and wombat have also been found to glow under ultraviolet (UV) light.

While we don’t exactly understand why, it is thought to be related to the animals’ preference for nocturnal or crepuscular activity (they are most active at night or dawn and dusk).

Birds, who are already famed for their colourful displays in the visible light spectrum, make use of biofluorescence too.

As if a puffin’s colourful bill wasn’t already enough—under UV light their colour is even more intense.

Some species of parrot also have biofluorescent feathers, which enhances their attractiveness to a mate.

Numerous species of finches from the family Estrildidae have prominent ‘beads’ of fluorescent material either side of their beaks when they are hatchlings, including Australia’s own remarkable Gouldian Finch.

The theory is that these ‘beads’ act like beacons for the parents—an illuminated ‘landing strip’ if you will—helping them feed their chicks accurately in their nest in a darkened tree hollow.

Lighting up the night

Fireflies are famed for their illumination, to help them find a mate.

But Australia is also home to several species of glow worms that use their bioluminescence for an entirely different purpose.

Despite their common name, glow worms are fungus gnats from the family Keroplatidae.

The term glow worm only applies to the larval or immature phase, after which they pupate into something resembling a small mosquito.

These predatory creatures dangle several strands of silk, dotted with sticky mucous, before lighting up their posteriors to attract insects.

In the darkness, the glow worms’ prey doesn’t see the snare until it’s too late.

Scorpions, on the other hand, are biofluorescent—their exoskeleton absorbs UV light and re-emits it at different wavelengths, giving the animal a remarkable greenish glow.

This fascinating group of arachnids have survived on Earth for more than 400 million years, but what advantage is there for a nocturnal hunter to glow in the presence of UV light?

While we do not know for certain, there are a few theories.

One is that the fluorescing reaction is incidental and serves no benefit to the animal.

Another is that the scorpions’ biofluorescence makes their body a UV detection system—something that could allow them to detect and respond to changing light conditions that would otherwise leave them exposed to predators.

It may also be a way for the scorpions to find a mate, or a warning to others that it is venomous.

Recent research has identified the presence of a fluorescing chemical in the scorpion’s exoskeleton, which has shown antifungal and anti-parasitic properties in other organisms.

Whatever the reason, it is an amazing thing to see.

We are only just starting to fully understand this phenomenon of glowing organisms but studying the extraordinary world of bioluminescent and biofluorescent creatures promises to be an illuminating journey.

Still in the dark? Ask Us a question