Fusion, feminism and food

From the ‘housewife's companion’ to the halal snack pack—flavours that flipped Australian kitchens.

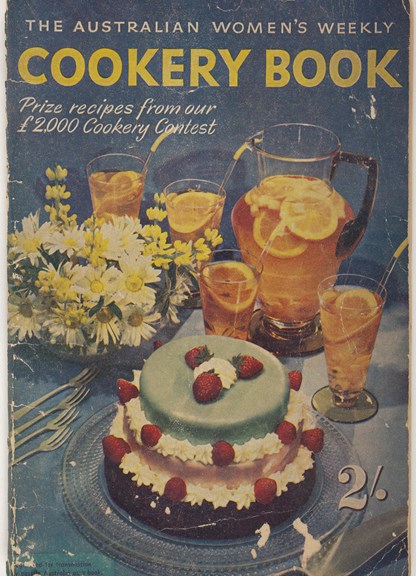

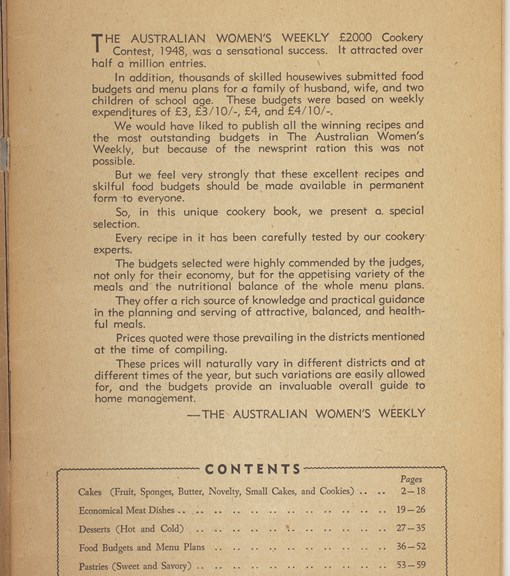

The year is 1948, wounds of another world war are raw, and The Australian Women's Weekly holds a £2000 ‘cookery contest’.

Declaring it a ‘sensational success’, the magazine’s forward boasts ‘over half a million’ entries.

‘Thousands of skilled housewives submitted food budgets and menu plans for a family of husband, wife and two children of school age,’ it reads.

But ‘The Weekly's’ ‘cookery experts’ can only pick one winner. For the meat section, they choose ‘the housewife's companion (shin of beef three ways)’.

Fast-forward to 2016 and a U.S. presidential election that reverberates around the world.

The Macquarie Dictionary asks Australians to choose a word that defines this tumultuous year. ‘Alt-right’ and ‘fake news’ get honourable mentions—but the people's choice award goes to: ‘halal snack pack’.

This polystyrene-ensconced dish of shaved meat and hot chips drowned under a sea of sauce—born to cater to Islamic requirements—has been embraced by late night revellers and now, officially, the public at large.

And, yes, it goes vegan.

So how did we get here?

Take a dive into Museums Victoria’s collections and archives—from the earliest to the most modern foods—and discover some of the recipes, ingredients and utensils that rocked the Australian kitchen.

Gallery

Even as The Weekly is giving gongs to ‘economy flapjacks’ and ‘oatmeal prune pudding’, the first ripples of a culinary tsunami are lapping upon Australian shores.

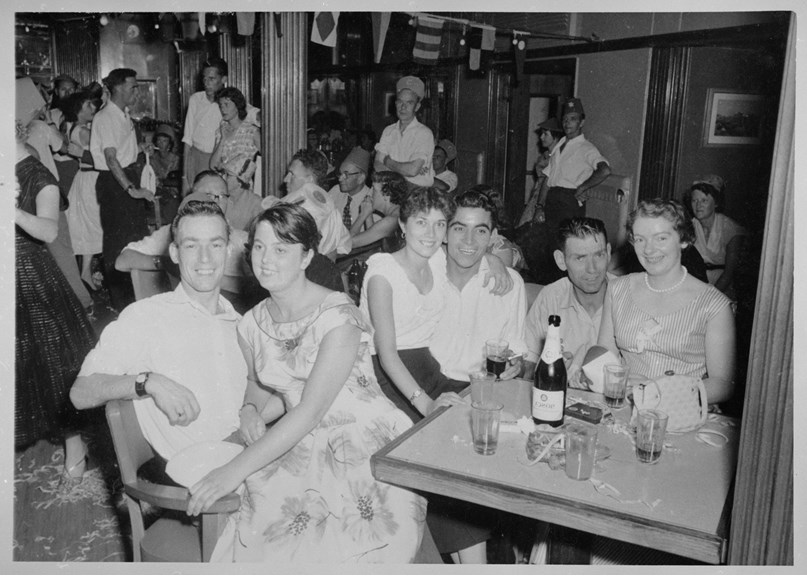

Between 1945 and 1965 more than two million immigrants will alight upon our piers and wharves. Around half are so-called ‘Ten Pound Poms’, another million or so come from other parts of war ravaged and impoverished Europe.

Together they will change Australian cuisine—even before they disembarked.

Going on in the kitchens of the ships which ferried them is a precursor to the kind of fusion cuisines which will sweep their new homeland, decades later.

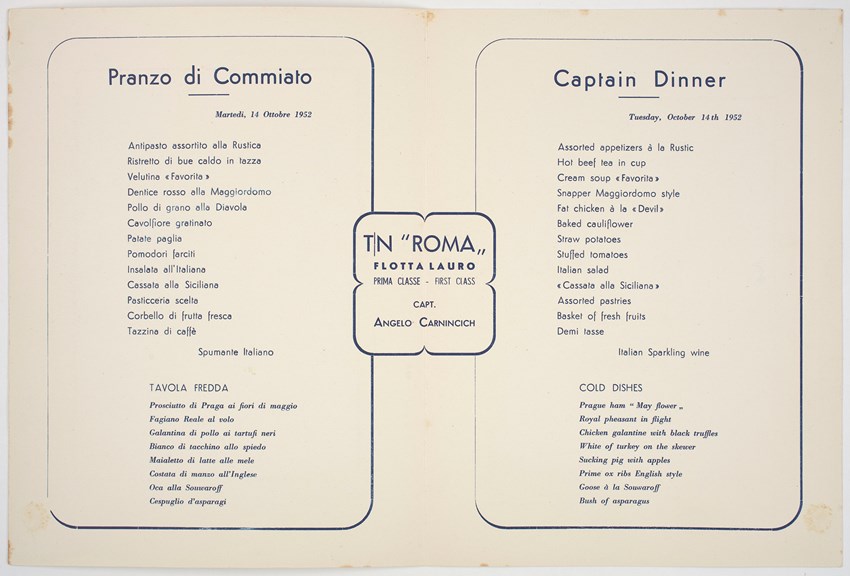

On converted British troop, ships Italians migrants are confronting English fare for the first time. Italian liners are adapting risotto and pasta dishes to the British palate. Dutch ships are serving ‘omlet sambal’ and ‘nasi goreng’—recipes taken from their Indonesian colonies—alongside Leyden cheese and pickled herring to Greek and Latvian passengers.

More than 200 shipboard menus in the museums' collection reveal the kind of ‘cultural intersections’ occurring onboard, MV Migration and Cultural Diversity senior curator Dr Moya McFadzean says.

We know, for example, that dinner on board Italian ship the Fairsea on Tuesday, 7 May 1957, is fish fillets à la Florentine with boiled hen in German sauce and Hungarian-style rice.

Along with this tangible evidence are anecdotes which make Moya wonder if seeds of culinary adventure were sown on these voyages. Seeds which would bear fruit in years to come.

‘Many [post WWII immigrants] do talk about that experience as an adventure,’ Moya says.

‘It’s hard to think that the food wouldn’t have been a big part of that.’

While food can be an adventure, for many it is also a yoke.

For much of Australian history, running a kitchen is a full-time job. And it’s a job which falls ‘overwhelmingly’ upon housewives, MV Home and Community senior curator Deborah Tout-Smith says.

But while many things remain the same, others will change—dramatically.

‘If we went back into a 1950s or '60s kitchen today, we'd be astonished at how much time women spent in the kitchen,’ Deb says.

First, the family is served breakfast. Then breads might be made, or biscuits, cakes, jams—from scratch. Tomorrow’s lunch for hubby and the kids won’t make itself. And we haven’t even got to preparing a roast for dinner.

In total, Deb says a woman could spend around four hours in the kitchen every day. Which of course, doesn’t include household chores like washing and ironing clothes, scrubbing floors ...

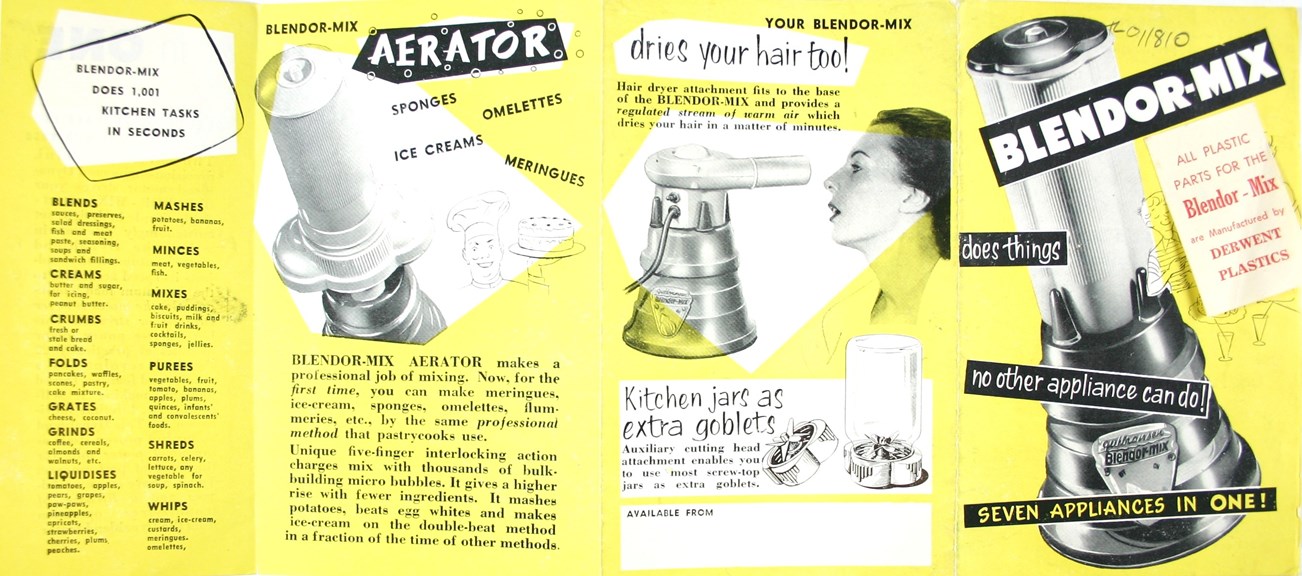

Then another influx of post WWII arrivals: mass-produced consumer goods like freezers, microwaves and slow cookers.

In 1973 a paid column in The Canberra Times, called Wine Talk, ‘discovers’ one such contraption: ‘an electric cooking pot’ perfect for ‘us career girls and working wives’ .

‘Switch it on low, before leaving for work, then a perfect dinner awaits your home coming, without being tied to a kitchen ... be the hostess with the mostess!’‘The Canberra Times’, paid column, 1973

Hardly gender equality, Deb says, but the humble slow cooker does ‘liberate a lot of women from the drudgery of the kitchen’.

If, with her new-found free time, our theoretical housewife takes a stroll around the block, she might spot what—to her—seem strange and exotic crops in the front yards of her migrant neighbours.

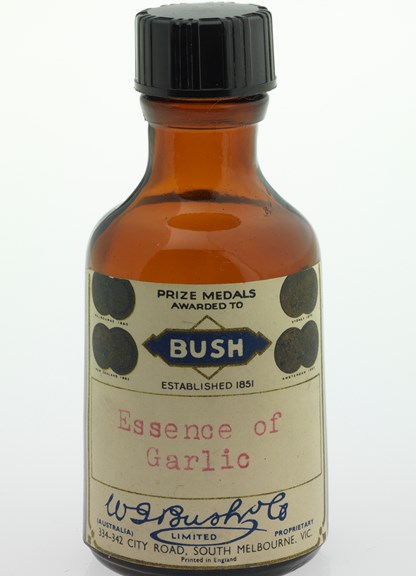

None would have as much impact on the Australian kitchen as Allium sativum, aka garlic.

In 2018 food writer John Newton pens a book which attempts to explain how Australian food went from ‘bland to brilliant’.

‘Those who colonised or invaded this country suffered from Alliumphobia, or fear of garlic,’ he writes.

So convinced is John of the pivotal role it would come to play in Australian kitchens, he divides ‘the history of non-Indigenous food into two eras: BG (before garlic) and PG (post garlic)’. He calls his book: The Getting of Garlic.

It wasn’t just garlic which took some getting.

We're back in 1970 and the Mecca family leaves Genoa in 1970 for their new home in Melbourne.

Laura, head of her young family's kitchen, finds local cooking confronting.

The bread is square and ‘plastic’. Every night she holds her nose and slams shut the windows when her neighbours' lamb chops hit the grill.

She does love the cakes, and from her adopted ‘Australian grandma’ she learns to master a fruitcake which she will still be serving to guests nearly four decades later.

Still the Meccas yearn for a taste of home. But when Laura sets out to procure a staple ingredient, she is shocked to discover cooking Italian-style will be a whole lot harder than she anticipated.

As migrants like the Meccas introduce their neighbours to novel ingredients, food processing corporations are selling them entirely new ideas.

The widespread embrace of U.S. commodities, and with them North American tastes, will make for some strange bedfellows.

For example: what do ‘Californian grapefruit cocktails’ and ‘colonial salad’—a concoction of fruit and jelly—have in common?

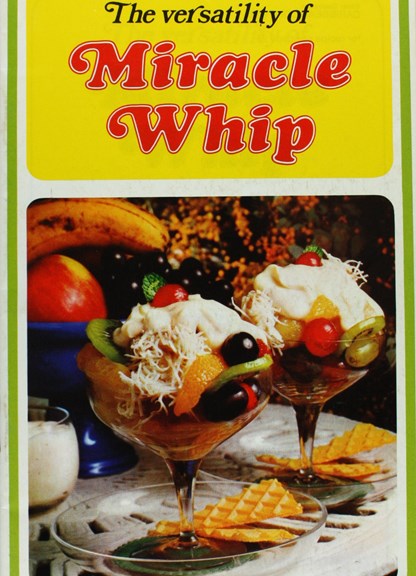

Well, for one, both feature in a food processing giant’s recipe brochure called The Versatility of Miracle Whip.

Home and Community senior curator Deborah Tout-Smith sums up the sweeping culinary changes of the ‘60s and ‘70s in two words: colour and shape.

The introduction of glossy, colourful brochures marketing mass-produced foods will forever change the look and feel of the Australian kitchen, she says.

This new wave—which breaches the barrier between sweet and savoury— finds its apogee at the cocktail party.

For all its cultural dominance, the U.S. does not have a monopoly on fast food innovation.

From at least the 1940s, entrepreneurial Chinese Australians are adapting Cantonese-style dumplings to the broader Australian palate.

And so, the story goes, the dim sim is born in Melbourne's China Town: bigger and meatier than its forebear. Melbourne becomes the first place to mass produce its beloved 'dimmy', which will soon become a staple at footy matches and corner stores around Australia.

By the time three Greek brothers buy a fish and chip shop in Shepparton, 1965, the dim sim is already a takeaway classic.

Decades later, now retired, middle brother Leo Ladas has nothing but fond memories of the one Victorian brand of dim sim to which he was always loyal.

‘I've been serving dim sims 47 years,’ he says.

‘They beautiful dim sims, beautiful. I used to eat about six or eight everyday. Black sauce, fried, steamed .... .’

The brand of which Leo speaks so lovingly is made by in Melbourne, by a Greek family business.

So perhaps the reaction of young Melbourne restaurateur Xinyan Wong or ‘DD’—from Chongqing in south-west China—to the South Melbourne Market's famed ‘dimmy’ is no surprise.

‘She was like, 'what's this?’ her partner, Kevin Houng, says in August, 2019.

‘It's essentially like a Chinese dumpling—but now it's been Australianised.’

To Kevin and DD, food is intimately entwined with both cultural history and personal identity.

For Australian-born Kevin, the Taiwanese beef noodles his older family members cook are a link to the land of their birth.

Still, he struggles to define his country's cuisine in 2019. ‘Chicken parma?’ he offers, and just as quickly retracts.

‘There is nothing you would call specifically Australian, it's all bits and pieces of everywhere,’ Kevin says.

‘Even a HSP [halal snack pack] is Australian ... but it's not.’

Written by Joe Hinchliffe, Museums Victoria