Forbidden objects in the museum's collection

What do a doll, religious text, gun, and surprised-looking cat have in common?

At one time or another, these collection items have all been considered forbidden but not always for the reason you might think.

More than this, they are often powerful objects that carry the history of change across human society over hundreds of years—and not just in Australia.

Seed smuggling doll

This is no ordinary children’s toy.

This doll was used to flout Australia’s strict quarantine laws in the 1960s, stuffed with smuggled plant seeds—a common practise by migrants, uncertain about access to familiar plants and vegetables in their new homeland.

It was originally purchased in Melbourne in 1963 as a gift for seven-year-old Maria Attardi, when she was in hospital with a broken arm.

Maria had migrated to Australia with her family, but on returning to Italy in 1967 her mother removed the doll’s stuffing and filled it with local plant seeds to give to relatives back home—in particular her grandmother, who loved collecting plants.

When the family returned to Australia 11 months later the process was repeated, this time with Italian vegetable seeds like beans, tomatoes, and lettuces.

‘My mum knew she was doing something wrong, but she still stuffed her bra, girdle and the body cavity of my dolls…and smuggled them in,’ recalled Maria.

Maria herself donated the doll to the museum in 2005—a significant, if quirky, piece of Australia’s immigration history.

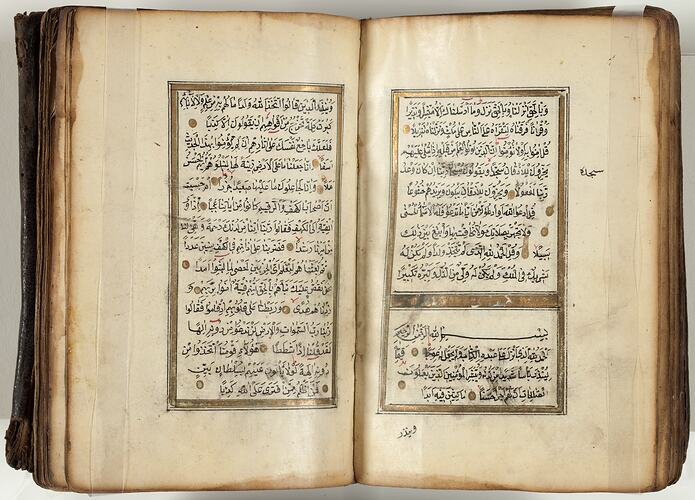

Qur‘an

Rather than being confiscated by authorities, this qur’an survived because it was hidden from them.

Created about 300 years ago in the days of the Ottoman Empire, it was used as a teaching text at the Silvi Xhami theological school, in the town of Ohrid—formerly part of Albania but now Macedonia.

The qur’an is entirely handwritten and would have taken six years to transcribe, but perhaps more impressive is its tale of endurance.

After World War II, the country’s communist regime cracked down on religious observance and the text was hidden under the floorboards of the mosque.

It was uncovered during a flood cleanup in the mid 1960s but, fearing it would be confiscated and destroyed, Lufti Lloga hid it and brought it to Australia.

Lufti’s son, Erik, donated it to the Albanian Muslim Society in Shepparton in the 1990s and it was, in turn, given to Museums Victoria in 2008.

It is on display at the Immigration Museum.

Dinosaur eggs

Fossils are rare and valuable, making them prime candidates for illegal trade—especially dinosaur eggs.

These eggs were smuggled out of China and seized by Australian Federal Police, along with hundreds of kilograms of other dinosaur, mammal, fish, and reptile fossils.

On return of the smuggled goods to Chinese authorities in 2008, China’s Ambassador gave six fossils to Australia in recognition of stopping the trade of these fossils.

This clutch of four eggs was gifted to Museums Victoria for the help it provided.

Dinosaur eggs are particularly valuable scientifically because they can provide insight into the nesting behaviour of animals long gone.

They are on display in the Melbourne Museum’s Dinosaur Walk exhibition.

Chameleons

Chameleons are incredible reptiles capable of hunting a variety of prey, reproducing rapidly, and changing their colouration to suit their environment.

All of which are good reasons why they are banned in Australia, to prevent them becoming an invasive species—as they have in other countries.

Despite their illegal status chameleons are highly-prized as pets and occasionally make it into the country, like this one.

It was one of three chameleons left on a Melbourne doorstep and surrendered to authorities before coming to the museum’s quarantine facility.

Ordinarily these animals would be immediately destroyed, but at Melbourne Museum they get a stay of execution as part of the live exhibits displays.

And it isn’t just reptiles—fugitive tarantulas are also a regular feature of Bugs Alive!

Leopard Cat

You may have come across this one before, as an example of questionable taxidermy alongside our resident star Sad Otter.

While there a no records of exactly where it came from, this surprised-looking Leopard Cat entered the museum’s collection in 1985 after it was seized by Australian Customs officers.

Leopard cats have historically been exploited for their fur, particularly across Asia, and they are protected from international trade for this reason.

And these felines are far from the only animals illegally imported into Australia as part of the larger black-market trade of prohibited animal goods.

The museum also holds several examples of animal goods confiscated by customs, including a rather macabre umbrella stand made from an elephant’s foot.

Ned Kelly commemorative revolver

This is an Italian-made replica of a Colt 1851 Navy revolver from 1980, which has been engraved to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Ned Kelly’s death.

It may seem odd at first sight because Colt Navy revolvers carry an engraving of the 1843 naval Battle of Campeche between Texas and Mexico, which appears beside the iconic motif of Kelly’s helmet.

Kelly, however, did wield a Colt Navy revolver that he took from a police officer.

It was confiscated by police after his capture at the siege of Glenrowan in 1880, along with his armour (of which there is also a piece in the museum’s collection).

But it is not just the connection to Ned Kelly that makes this revolver worthy of inclusion, as it also represents another significant moment in Australian history.

After the 1996 Port Arthur massacre Australia introduced a suite of strict gun laws—most notably the National Firearms Agreement.

The federal government launched schemes to buy back now illegal firearms that same year, and again in 2003 when handgun ownership was further restricted—which is where this revolver fits in.

It was surrendered as part of the second buyback and saved from destruction by Victoria Police, who offered it to the museum along with several other firearms.

Opium scales

These scales are part of the far-reaching legacy of the British Empire’s drug trade and the subsequent campaign to stop drug use in Australia.

In the 1800s the British used smugglers and pirates to illegally import opium into China and went to war (twice) to keep Chinese ports open to the profitable narcotic.

Opium smoking became widespread and the practise followed Chinese migrants overseas to other British colonies, including gold rush-era Victoria.

The trade, and the taxation revenue it generated, was allowed to continue until politicians determined a need ‘to protect white people’ in the early days of Australia’s Federation.

Victoria outlawed opium in 1905 and customs officers began raiding Chinese premises—which is where these scales were seized, among other opium paraphernalia.

The Customs and Excise Department later donated them to the museum, in 1939.

Sword Stick

Concealed weapons are definitely a no-no these days but this one is a little different because it was owned, and used, by a customs detective no less.

Detective Inspector John Christie, also known as Australia’s Sherlock Holmes, was famed for using disguises to make arrests as a police officer but it was those unconventional tactics that also played a part in his resignation in 1857.

Nearly 30 years later he joined the Customs Department and rose through the ranks to detective.

He tracked down opium and tobacco smugglers, bootleg booze, prohibited books, and bubonic plague material.

Christie was forced to retire in 1910, after he was injured in a fight with knife-wielding opium smugglers on the docks.

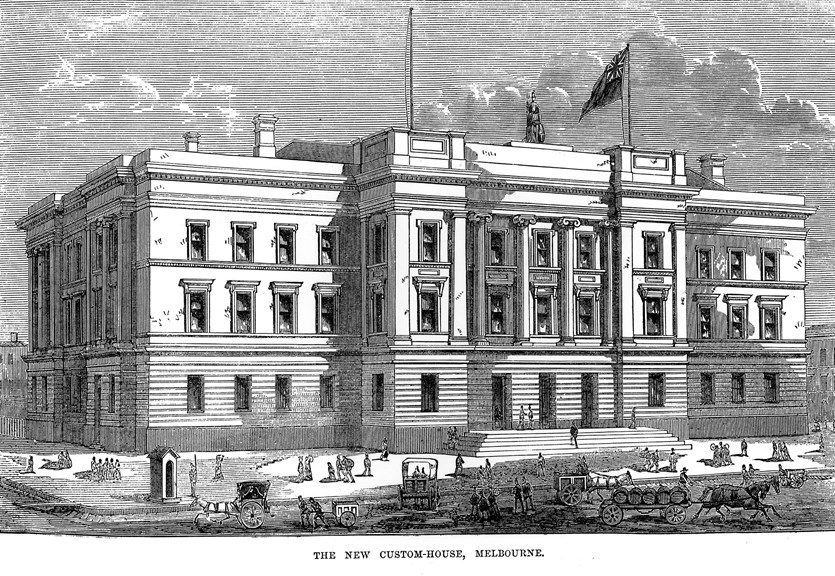

His sword stick is on display at the Immigration Museum which, incidentally, also used to be the Customs House—the venue where all this contraband would have been stored.

During Victoria’s gold rush, the building was at the centre of a busy trade port and customs officers were responsible for stopping the trade of illegal items and calculating the duty to be paid on imported goods.

After customs officers left in 1965, the building was substantially altered and used as a parliamentary office for decades.

It had to be extensively restored before it reopened as the Immigration Museum in 1998.

It’s good place to look if you’re keen to explore more confiscated things from the museum’s collection.