Flight of fashion: when feathers were worth twice their weight in gold

In the 1800s, the fashion industry’s obsession with feathers drove some bird species to extinction.

Can you imagine paying $1000 for just 30 grams of feathers?

To put that in perspective, it’s about the same weight as a pencil.

That may sound ridiculous now but at the turn of the 20th century, the public appetite for ornate plumes was so great that feathers fetched obscene amounts of money.

It also spelled the end for some bird species.

You may be asking, what drove this appetite?

Well, the answer is hats.

Feathers have featured in fashion throughout history, but in the late 1700s the Industrial Revolution started to bring luxuries to the masses.

With so much available to so many, the problem became how to stand out from a crowd.

Milliners, or hat makers, were among those to take advantage of new technology, providing vibrant designs to add some drama to women’s fashion.

The problem was, they were too successful.

Feathers became a status symbol coveted by the new mass market and were produced on an industrial scale throughout the 1800s.

Birds were hunted around the world to supply plumes to centres of fashion, including London and New York.

And it was women who were often blamed for the trend.

In 1865, renowned ornithologist John Gould wrote to Museums Victoria’s first director, Sir Frederick McCoy, complaining that he was unable to fulfil a request for bird specimens for the burgeoning museum’s collection.

‘The Ladies, the Ladies, have however, so stripped us of birds for their bonnets that but few are now in the market and these of course are high priced,’ Gould wrote.

Ironically, Gould and his colleagues were killing birds by the thousands around the same time (in the name of science).

On a walk in New York in 1886, the American Museum of Natural History’s ornithologist, Frank Chapman, infamously observed some 40 native bird species on women’s hats, some with an entire stuffed bird attached.

An ornithology publication in 1887 pointed to women as ‘the indirect, but real, instigators of this slaughter; all that can be hoped for is that the freaks of feminine vanity may take some other and less harmful direction’.

Herbert K. Job wrote of the scarcity of herons caused by the millinery trade.

‘The price for plumes offered to hunters was $32 per ounce, which makes the plumes worth about TWICE THEIR WEIGHT IN GOLD.’

In today’s money, that’s about US$1000 per ounce (28 grams).

Job recalled that in 1902, over 1600 packages of heron plumes were sold at just one London auction house.

‘As it requires about four birds to make an ounce of plumes, these sales meant 192,960 herons killed at their nests, and from two to three times that number of young or eggs destroyed.

‘Is it, then, any wonder that these species are on the verge of extinction?’

And the issue wasn’t just confined to the other side of the world.

In Australia, egrets, herons, lyrebirds, bowerbirds and emus were amongst the species targeted by plume hunters.

Lyrebirds are ancient—their earliest known fossils are 15 million years old—but the species came close to extinction in the early 1900s, hunted for its ornate tail feathers.

In the 1911 publication Pros and cons of the plumage bill bird protectionist James Buckland wrote, ‘over 400 lyre-birds were killed in one district in a single season to supply the London plumage market’.

The Australian Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) was founded to promote the study and conservation of the native bird species of Australia and adjacent regions.

One of its members, Tom Tregellas, regularly camped out in a large hollow tree trunk over a 17 year period to observe and photograph the birds in Sherbrooke Forest, east of Melbourne.

Noticing a decrease in the population over time, he successfully crusaded for legislative protection of lyrebirds.

Fashion led to a rapid decline of several species, and not all of them were afforded protection before it was too late.

The Huia of New Zealand was declared extinct in 1907, and it is also believed that the use of Great Auk feathers for down partially contributed to its extinction.

While women were loudly condemned for their role in consuming feathers, they were also instrumental in raising awareness of the issue.

In 1896 the American socialite and amateur naturalist Harriet Hemenway and her cousin Minna Hall led a boycott of feathered hats which attracted 900 participants.

The action led to the formation of the National Audubon Society and passage of the Weeks-McLean Law (the Migratory Bird Act), which outlawed market hunting and the interstate transport of birds.

Periodicals, books, and public lectures were also instrumental in inspiring action on bird preservation.

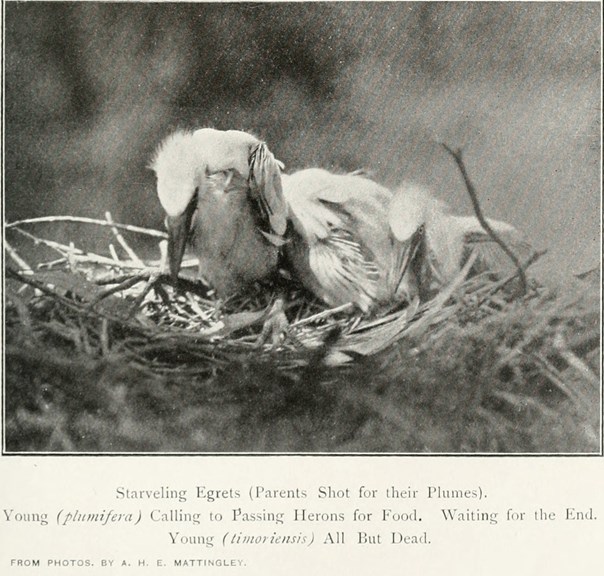

The AOU’s journal, The Emu, published several articles by Australian ornithologist Arthur H. Mattingley documenting the devastation caused by plume hunters.

Near the Murray River, Mattingley photographed ergret and herron nests.

Over the course of few weeks, he discovered nearly one-third of the birds had been killed, and the young left to starve in their nests.

His article, Plundered for their plumes, gained attention throughout the UK, Paris, Amsterdam, Italy, Spain, Denmark, Australia and the United States.

The photos are widely regarded as a tipping point in the use of feathers in fashion.

In England, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) posted the photos on billboards and in shop windows, and in 1911 men protested against the wearing of feathers using enlargements of the story in London’s West End.

By 1913, international plume markets started shutting down as feathered fashion fell out of favour.

Feathered hats did make a comeback in the 1930s-1960s, but hats lost popularity in the subsequent decades as they were no longer a standard item of women’s daywear.

That's not to say feathers have disappeared from fashion entirely—marabou and ostrich feathers still appear on fashion runways and award show red carpets.

One of the few places you can still see feathered headwear is at the Melbourne Cup, though the plumes may not all be authentic.

The use of down in winter jackets continues to be contentious, and several major brands have moved to high-tech synthetics as a result.

But while mass market fashion continues to grapple with serious environmental issues, the history of feathered hats shows that wide-scale change is possible—for the better.

By Museums Victoria Librarian Hayley Webster and former librarian Gemma Steele.