Do centipedes really have 100 legs?

Despite their name, it’s impossible for centipedes to have exactly 100 legs. Find out why, what the legs are for, and if centipedes are dangerous.

If you’ve ever seen a centipede in your house or wandering through the soil, you may have noticed that its body is divided into segments.

Look closely (but not too close—centipedes do bite!) and you may notice that each segment has a single pair of legs.

This differs from millipedes, who have two pairs of legs on each segment.

Centipedes can have 15 to 191 pairs of legs depending on the species.

It’s not clear exactly why, but the number of segments and leg pairs of a centipede is always odd.

While ‘centipedes’ means ‘100’,100 scuttling legs would require 50 pairs—an even number—so you won’t find a centipede with exactly 100 legs.

So, why are they called ‘centipedes’ at all? Well, it’s probably just a little easier than saying ’30-to-382-ipedes.’

Why do centipedes have so many legs?

‘Tough question—like why is the world round?’ muses Dr Ken Walker, senior curator of entomology at the Museums Victoria Research Institute.

It may have something to do with the sheer length of these creeping critters. A longer body is easier to carry with an even distribution of legs.

‘Multiple legs provide a simple solution to weight distribution and movement of an elongated animal,’ says Ken.

Centipedes do have legs with extra-special functions. Look at the tail end of a centipede and you’ll find a pair of back legs that look a bit like antennae.

This pair of legs is modified in length, thickness or even colour. Different centipede species have developed different and amazing adaptations for these back legs.

Depending on the centipede species, these back legs may be used for tricking predators into thinking the back end is the head, or for stabilisation when running (like a tail).

Centipedes may also use their back legs for courtship, attack, defence or just holding on tight.

Some don’t just look like antennae, but may also act like antennae, with chemical receptors for sensing their complex environment.

Are centipedes dangerous?

Centipedes are venomous, but how do they sting? These animals have evolved a remarkable way of delivering their venom to unsuspecting prey (or people).

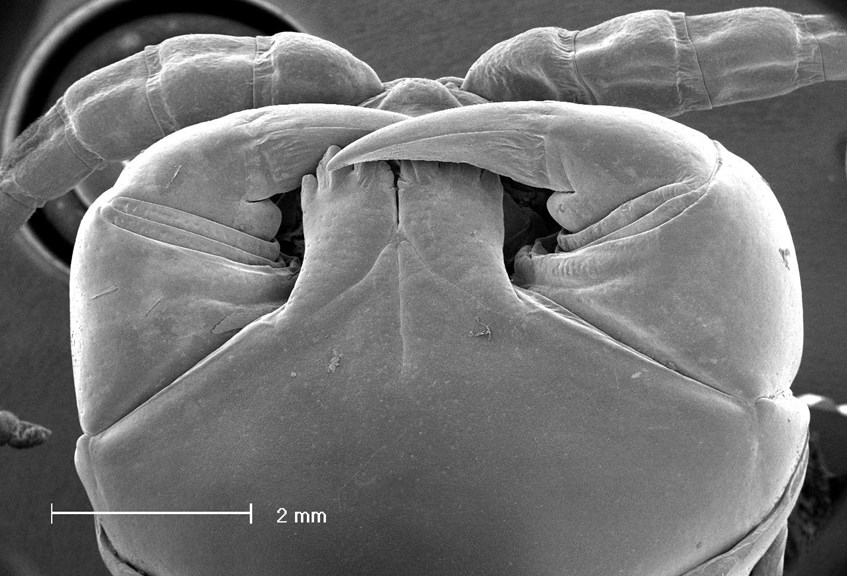

Centipede pincers are called ‘forcipules,’ and are actually a modified pair of legs. Look at the front end of the centipede and you can see how the leg structure has been adapted for a completely new purpose.

Also called ‘maxillipeds,’ these forcipules are linked to venom glands.

Compared to spider and snake venom, we know less about the centipede’s weapon of choice. But, like this venomous cone snail, studying their venom may help us unlock new potential in the world of drug research.

Although they look a little frightening, centipede bites are very rarely fatal to humans.

Still, centipede bites can cause pain and swelling, and you never know if you may be allergic—so best to steer clear of the biting end anyway.

While centipedes are unlikely to kill humans, they do use their venom for another purpose: immobilising a tasty snack.

What do centipedes eat?

Centipedes are voracious hunters.

They are active predators that will feed on invertebrates including earthworms, spiders and insects. Their potent venom is a vital weapon in taking down their prey.

And they don’t just stick to the world of bugs and spiders.

The especially large centipedes will chase down invertebrates including rats, amphibians, reptiles and bats.

What roles do centipedes play in our ecosystems?

We can imagine how a lioness may stalk her unsuspecting prey, how a bear may fish for salmon, or how an owl may snatch a mouse.

Without these predators, prey populations would be out of control and balanced ecosystems would be overrun.

The complex ecosystem of the soil is no different.

‘Predators (such as centipedes) and parasites are the population control mechanisms of the nature,’ says Ken.

‘Without population control mechanisms, different groups could overpopulate and destroy a food source or habitat.’

Like all predators, centipedes are vital part of their ecosystem and ours—legs and all.

If you want to know more about the wonderful invertebrates in your ecosystem, find out what critters you can find in your own backyard.

Discover a world 4 billion years in the making. Visit the Our Wondrous Planet exhibition at Melbourne Museum and experience the incredible connections that unite all life on Earth.