Deaccessioning: Why do museums remove objects from collections?

The public collections found in museums across the world are a historic record. But that does not mean everything can stay there forever.

Museums like ours, and the people who work here, love to collect things.

As with your own collections at home though, sometimes we need to take a step back and consider if we really need to keep all the things we have.

Especially if it is a duplicate. Or we do not own it. Or it could explode.

So, what happens when something is no longer suitable to be kept in the Museums Victoria State collections and needs to be removed?

It is a process called deaccessioning.

Dangerous goods

Museums Victoria is the caretaker of about 15 million objects, and it is a collection that is constantly growing.

There are many reasons why an object is brought into the collection, especially if it is of scientific, historical, or cultural value.

Among the many reasons to dispose of something though, one of the more pressing is that it poses a serious hazard.

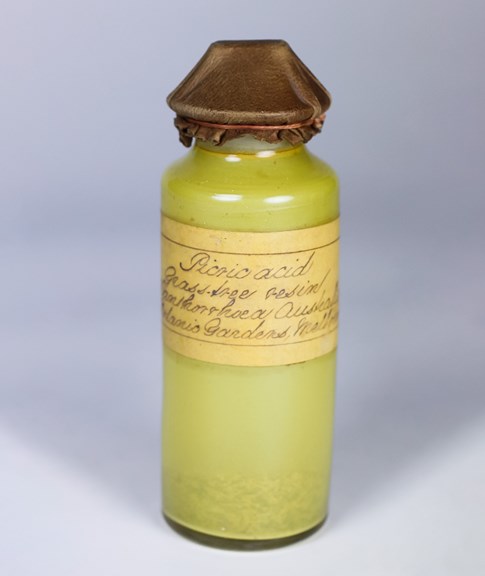

Take this vial of picric acid, which was collected from a grass tree (Xanthorrhoea australis) in the Royal Botanic Gardens in the 1880s.

Picric acid in liquid form is not a problem and has been used as a yellow dye and an antiseptic.

But after about 130 years in the collection this sample had dried out and, when it crystalises, picric acid is highly explosive.

Even taking off the lid could crack a crystal and cause a significant explosion.

So, the vial was deaccessioned and carefully removed by an explosives expert who took it to an empty field and blew it up—just to be safe.

Giving back

Colonial institutions, including Museums Victoria, did not always show the same care in collecting objects as they do today.

Consequently we have to deal with the legacy of decisions made by those in times past, often more than 100 years ago.

To put it bluntly, some of the objects in the collection should not be there because they were acquired in what we now understand are legally or ethically indefensible ways.

For these types of objects we have a moral obligation to repatriate them, to Traditional Owners both in Australia and abroad.

And to be repatriated, the objects must first be deaccessioned from the collection.

However, there are cases where something was collected legally and ethically but still needs to go.

This lizard was collected in north western Queensland during field work in 2005 and was used to describe a new species, the Five-lined earless dragon, in 2014.

Once it became the holotype specimen (the first specimen that forms the basis for a species’ description), its collecting permit required that it be removed from our collection and transferred to the Queensland Museum.

Museums Victoria has another example of this species (also known as a paratype) that was collected at the same time and location as the holotype.

An exact science

Museums Victoria Research Institute is constantly obtaining new scientific specimens from field work—on land or sea.

But to learn something new, occasionally scientists must employ testing techniques that might damage or destroy the object.

Mostly this only requires a small tissue sample from a larger specimen—as with the genetics work performed on Tasmanian Tiger specimens from the museum’s collection.

In the case of smaller genetic specimens, like those preserved in the Ian Potter Australian Wildlife BioBank, that may not always work.

Sometimes the science we can learn from testing a specimen is more valuable than keeping it, especially if it has already been repeatedly sampled.

When assessing the impact of the 2019-20 Australian bushfires, scientists had to use the last of three tissue specimens—two from southern water skinks and one from a Pobblebonk frog.

This meant deaccessioning the specimens, but provided valuable information about how we can help these species recover from devastating fires.

For the good of the collection

Despite our best efforts, there is no stopping an object’s natural deterioration—we can only delay it.

Eventually this decay can eradicate not just the physical object, but also the values that made it part of the museum’s collection in the first place.

Plastic, film and photographs are particularly vulnerable and one method of slowing the degradation is to keep these objects in cool storage.

But it is not always an option.

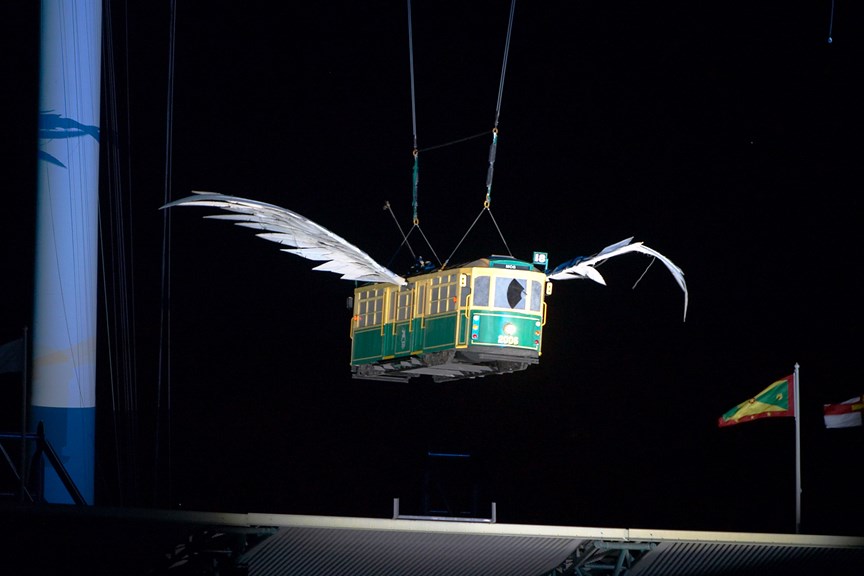

The iconic flying tram came to the Melbourne Museum immediately after its performance at the 2006 Commonwealth Games opening ceremony.

Aside from the steel and aluminium frame, it was mostly built out of lightweight, easily degradable materials.

While these materials were well suited to its original purpose, they limited its lifespan to about 20-30 years.

By 2021 the tram’s body and its large foam-covered wings had already deteriorated to such an extent that preserving it in its already degraded condition would have meant storing the tram in an oxygen and moisture free environment.

Given it was acquired for display, this was not an effective use of the museum’s (unfortunately limited, and publicly funded) resources.

Since the Commonwealth Games collection contains other items that can tell the tram’s story, it was recommended for deaccessioning.

Seeing double

While you may have a collection of loose change at home, it (hopefully) does not come close to the extent of the museum’s numismatics collection.

And given there are so many coins, collected over such a long period of time, duplicates are an inevitable result.

One example is a square penny, produced by the Melbourne Branch of the Royal Mint between 1919 and 1921.

These are quite rare and valuable, and the museum is fortunate to have quite a few in its collection—dozens in fact.

But there comes a point in a collecting institution’s life when it must consider: how many is too many?

While many of the reasons for deaccessioning collection items result in their destruction, this is one of the rare occasions when selling an item is an acceptable option—because the penny had been purchased by the museum.

Selling these objects allows the museum to put the funds back into maintaining and improving the collection.

And no, before you ask, the museum isn’t selling any more at present.

The process

While these are some of the reasons for deaccessioning a collection item, each case requires its own careful assessment, and it is by no means a quick process.

It is a big deal to remove something from the collection.

A proposal must go through multiple levels of recommendation and endorsement, including the museum’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Advisory Committee for any items that are, or incorporate, First Peoples cultural material.

Once that is done, everything must be approved by the Museums Board of Victoria before the deaccessioning process can be finalised.

And if that is not enough, there is also usually a 12-month cooling-off period before we dispose of it.

This is just in case any new information comes to light that may affect the decision.

So, as you can see, deaccessioning is not quite as simple as you deciding to throw something out or put it on the nature strip.

But it is all part of the duty of care we have as custodians of such an important public collection.