Yulendj group

Yulendj is a Kulin word for 'knowledge and intelligence'. It is the name that members of the Bunjilaka Community Reference Group chose to describe their role in the First Peoples exhibition.

Yulendj comprises a group of 16 respected community members and Elders from across Victoria. They have generously shared their knowledge and experience to shape this exhibition into one that represents the diversity, history and pride of Koorie peoples.

Celebrate us, celebrate the Country you’re on, celebrate your being.

I struggled because of lack of education, lack of skills. It took me a long time to understand that I had something else that no-one else had. I had a mum that gave me stories. What went before me was my rights, my birth rights of who I am. Maybe it was her strength, Louisa Briggs’s strength, her granddaughter’s strength, and my grandmother. They’ve all instilled something, a pride. I carry generations of resistors and resilience. I’m a vehicle of many people who went before. I'm starting to try and give them a place, honour their place in history.

I don’t think people give us much recognition, even though Victoria has probably the most political mobilisers. Just look at William Cooper. Look at Derrimut, look at Ningerranaro, look at Barak. All these people left us a legacy, and if we can’t honour them, who can? The early borderers, the early resistors, all played a role in the history of this country. And who can tell their history but their descendants?

Yulendj is all those stories of connection, in a safer environment than we’ve ever had before. To be able to feel safe, teach people to see us, hear us and that we still play a major part in the history of this country. And it’s really good catching up with other people who you are part of. Learning about each others' stories. You’re in awe of them, and they’re a part of something that's bigger than all of us.

We've got to leave that legacy for the next generation. We need to give them a sense of place and identity or they'll merge into the mainstream. We're seeing amazing things emerging, like film, the continuing sporting prowess of our young people, having other heroes to celebrate. It will not just be this state, it will be a national and international standard of excellence. I think that takes strength of character dealing with a lot of issues that you have to deal with in an institution. We’ve also got to celebrate that the institution is allowing us an opportunity to play a major part in the next stage of our history. We’ll actually be seen as the descendants of a generation of people that never gave up their sovereignty, never gave up their struggle. We just come in different shades, but there's a whole intelligence emerging, of all the struggles that went before them. And the only way we can honour them is to give a major focus on something that is very uniquely Victorian.

You have a commitment and a responsibility, you can't be secure unless you bring people along with you. Sometimes I've always wanted to run away and just be my own identity. It would be easier I think. But I believe I had an ability to do other things – my mother instilled that into me, and I finally listened when she was gone. And it all started to make sense. I think we don't know these things until later on in life when that strength of family has given us some sense of belonging. I believe in family because of community, understanding community is family. And you have the obligations to give back, directly or indirectly. So when I worked with the kids that mightn't have had their family, you’re like their extended family. When I worked in education, when I was setting up child care centres, it was all about what I understood about what family was. We all have an obligation to care for each other.

So if anybody asks me, I'm made up of a whole lot of other people that have contributed to my thinking, who have given me strength of values and beliefs, that family is the essence. I think we as Elders have to keep re-awakening ourselves, to keep up with the impacts and changes that are occurring, because I think that we’ve got to understand that we live in the now. We’ve got to be confident enough to say, celebrate us, celebrate the Country you’re on, celebrate your being.

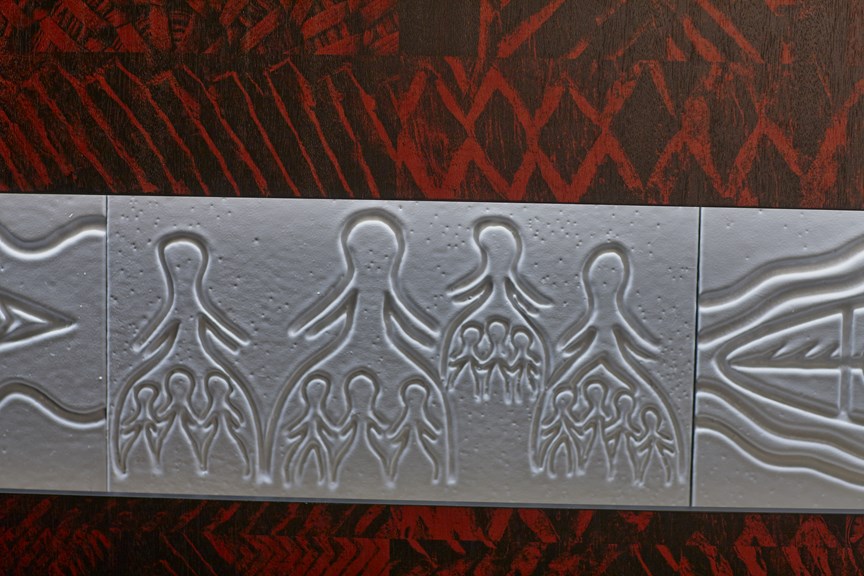

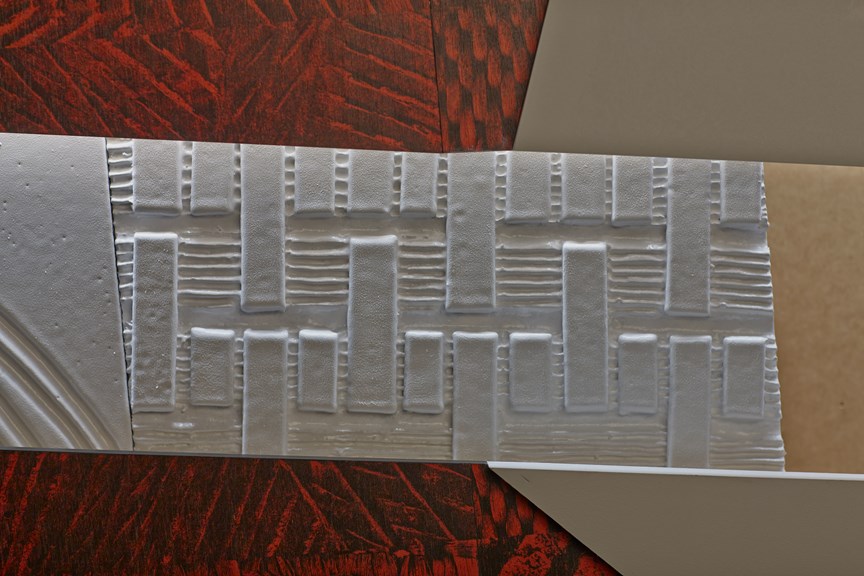

My artwork has helped me to tell my story.

My mob's Gunai/Kurnai. I was born at Lake Tyers Mission Station. Now it's known for its traditional name, Bung Yarnda. I grew up there with my parents and ten siblings, my grandparents, my uncles, aunties and cousins.

I was happy there. My favourite memories would be a bit of everything. Going to school, swimming, sports. I liked athletics - running - I know I was good at it. Jumping over those hurdles, going on picnics. There were lots of good things - sitting by the huge fire out in the dark, stars in the sky, listening to stories. There were stories about the Doolagahs and Narguns, Mrarts, all those myths and legends. I think they're easily the things that inspired me with my art.

I left school when I was 14. I started studying in my early fifties, back in 2000. I was a bit terrified to go back to study but I thought it was a good thing because I didn't have an education after I left. I had nothing. My siblings, cousins, didn't want to go. I must have become a leader, like a role model for them, and they followed me. Studying brought me a lot of achievements which I never thought possible and I'm really proud of myself. I started painting when I went back to study. It helped me to go back to all the things that I remembered.

What inspires me is what I see - the trees and leaves, the water, the grass, all those little things, even the markings on the stones when I'm having a look around the beach. I see patterns and symbols in everything. Those are the things that inspire me. It helps me.

I 've noticed in the last couple of weeks when I've been out there talking about my artwork, I've left some kind of an impact by telling my story because the artwork is involved in my whole life. I remember telling my brother about my life story. He was very interested and he said to me, look sis, you should write a book. I said no, I don't think so. I came back to Warragul about 1999 and I met a woman, Carolyn Landon. She was the author of Jackson Track: Memoir of a Dreamtime Place. She loaned me the book on Jackson's Track and I read it. It gave me some inspiration on doing my own story, so I approached her to ask if she could help me with my book. She wasn't too sure because she said, what would people think for a white woman to help a black woman to write her story?

We met up at my house maybe once a week. It took us about three, four years to complete the book. So there was lots of meetings and lots of teary times, like it was really hard for me to tell some parts of my story. I think every time I cried, she cried. Then a bit later on I had all my artwork, also photographs out on the table one day and she asked if she could take them home with her. As she was typing up what was taped she'd be looking at the artwork, then she realised that my artwork also came out into the story. My artwork has helped me to tell my story. Yeah, I think without it, I wouldn't be able to tell it.

The manuscript was done and I had an urge to ring them and tell them to cancel it. I in the end I just put the phone down, I thought, oh no, I won't worry about it. Then a week later it arrived and I re-read it. I must have read it about three four times and I was completely satisfied with the book because it helped me to understand all the things about my life and why it happened. Also to be able to forgive my parents. I know life wasn't meant to be like that for my parents as well because I know they suffered too as well as my siblings. So my book has helped me to really understand a lot of things, even with white people, how we were treated. I think it's important for them to know what happened. It gives them some insight on the impact. When my grandchildren have children, they can just pass it on to them and look, this is what happened to your great grandmother and you should be proud of her because she achieved all these things. I want them to be proud of me.

I get a lot of good comments on the book from people. I've collections of letters, cards, articles on the book. My artwork as well. I completed the Koorie art and design 2001-2002, so that's two of those awards. I'm really forgetting what I've achieved! I also got the 2004 award for Victorian Artist of the Year for NAIDOC.

In the very early stages of Yulendj, I really didn't know what I was getting myself into. But then I found it very interesting, a learning experience for me, to be able to work with staff members and to come out from Warragul, just helps me to get away outside and enjoy myself up here. I love every bit of it.

I can't wait for this whole project to come an end to see all this beautiful work out there. I think it was really interesting to have a look at all these objects, to find out if there was anything belonging to my father because he made artefacts, and also looking at the baskets. My grandmother's a well-known basket weaver.

I'm proud of what I'm doing for my people in East Gippsland. I am excited about it. The other project, possum skin cloak, that was a big thing too but this one's quite different. I know it's going to be huge.

The community wanted to see it and say it, and that was it. They've made it simple for themselves to bring that language back.

My Country is Taungurung and I’m the Taungurung language worker. I was born in Alexandra which is actually on Taungurung Country. Growing up in Healesville we never had any racism going on. We were just treated like everyone else. Every year we would go on holidays to Frasers National Park which is on Taungurung Country. They were the best days.

At the moment I'm studying Linguistics at Monash University and racism is very high. I've got another year and a half to go. I was so shocked that people teaching Indigenous Studies are non-Indigenous people. So I'm there now trying to put someone in there, to go get their PhD in Indigenous Studies and go and teach it. The young ones, not me - I'm too old.

It's really opened my eyes going back to uni just seeing non-Indigenous and Indigenous people doing Indigenous Studies and sitting there listening to Elders tell stories. We've got young Indigenous students at Monash Uni that learn through Indigenous Studies because they've never gone through what I've been through, and they get excited about learning something new. It's very hard for a middle-aged student to go in and listen to all that again but I understand the young ones learning it. A lot of the non-Indigenous said they've only learned about the Stolen Generations at high school and that was only a little bit. It needs to go back further than Stolen Generations for them to understand before they get to uni. I think they will learn a lot more walking through First Peoples than probably six months of studying Australian history that Captain Cook was a good fella.

I started with Yulendj and then I started Uni, and I had no time to get back to Yulendj. But I'm proud that I’ve been involved in it. My mum’s photos, videos and her stories were in the last exhibition of the museum and I just wanted to share what she gave me to this group. When I walked through First Peoples, I had goose bumps even though it wasn’t finished. It's going to be magnificent. It's really going to be magnificent. I can't wait to see it and I'm going to take a day off uni to go and do it.

The two Taungurung words that mean family for me are Gaan and Dhulin. Gaan, the cockatoo, is our family totem. When I say that word I can see my mum and my kids and it just brings us back together because my mum's not here anymore. My daughter Kaitlyn just turned 14 but when my Mum got sick she wasn't even at school. Kaitlyn and my Mum would sit there and play cards and they just got on like a house on fire. If she went in to hospital Kaitlyn would just sit with her all the time and Mum would tell stories and Kaitlyn would listen. Kaitlyn learned a lot of stories because my mum, having dementia, all she would do is go back in time. They were both on the same wavelength. So Gaan will bring myself, my mum and my daughter together. It's very short but it's powerful.

Dhulin is a lizard. My mum was the oldest in the family of 12 and my aunty was the youngest. My aunty and I were very close. Wherever she went, I went. We were like mother and daughter and she's not with us anymore either. I think it's the strength of Aboriginal women within that circle that I've built around these two words that keeps me going and I know my daughter will keep it going.

In 2007 my aunty retired and I took over the language. Before that we had a list of 300 words. We would have language camps on a yearly basis - people would go on Country and be involved in language. All of us were English speakers so that's how we were looking at those words, as English letters. When I took over from my aunty, I spoke to her and my mum and I said, there's got to be something in these letters that is not English. This does not sound like our Ancestors' language because of certain words that were coming in to us from the community. I said I don't know how long it's going to take but I want to do the research.

I sat there for nearly four years without any linguistic knowledge whatsoever, but with the help of the community linguist at VACL. I had 12 historical sources and different spellings for the one word. It would probably take me 45 minutes just to work out one word from all the different spellings and then once I'd got that all done, I would go back to the community. I'd give them options for a sound with a letter. Then the community decided on it. They were quite happy that I did all the background work because I was a community member as well. I was in the same boat - I wanted it to be easy. I wanted to just open up that book, have a look at that word and say it.

‘To see a word and say it’ is my community's motto. So the orthography in the dictionary is one sound, one letter. If it's a ‘gee’ sound, it's dj and if it's a ‘guh’ sound it's g. The community wanted to see it and say it, and that was it. They've made it simple for themselves to bring that language back. I ended up with over four and a half thousand words. I'm so glad that I did what I did.

I remember when I first started doing the dictionary, the Gunai had their language and I was thinking, how come we have never done this before? We should be up where they are. And I think that just pushed me further and to get it done for my community. It didn't matter whether I was getting paid to do it or not, it just came from the heart. You can ask my husband, I'd be up at 3:30 in the morning if there was something on my mind. It was such passion and when my aunty was doing it before I took over, it was exactly the same thing. She wanted our language to come back in to circulation. Aunty Judy was the one that I looked up to. She was there when my mum had passed and the only thing that I wish is that they were alive to see the book. I dedicated it to my mum and my aunty and my uncle. It's here for future generations and that's what matters now.

You've got to look after the land for the land to look after you.

My real name is Melissa Jones. People know me as Lisa. I'm from Mildura area, Ladji Ladji. Mum came to Melbourne to work. We lived in Braybrook and then we lived in Sunshine. She had two jobs and she never got the pension until 75. And we had Nan there, she was a shearer's cook. My family is women-driven so we all have a voice.

My brother Michael was a boxer so we had the cousins come down from Robinvale, the boys. We used to love it, dropping them big medicine balls on their bellies. There was heaps of us. Nan managed to feed us all and keep us going, and Michael boxed.

When we lived in Fitzroy, we used to go to a youth centre. We used to go to the Cubbies and then when you're old enough you could go to the FC. We went away to snow camps and when I was sixteen I was paid as a leader to go and teach a lot of young kids how to ski. Every year we'd go up to the snow and I'd teach them how to ski, and go rock-climbing, survival camps. We went up to Uluru for the handover. First time I'd been to a corroboree and it was scary, fascinating, all in one.

Mum's husband died at war, my sisters’ father and my brother's father, so mum wasn’t married. Uncle Dick used to look after Michael and Nanna Maude had Janette. My sister Janine was with my mum and her mother and they used to pick grapes in Swan Hill. When they see the black car coming, Janine would have to hide in a suitcase and she'd be pushed under the grapevines. She used to say sometimes she'd be let out when it was night time. That's how she remembers running from this black car all the time.

We never went through that because Mum brought us this way, Mum worked, Mum fought when welfare come around. I don't know how Mum kept us all together. She must have been very resilient because there were eleven of us in the house and never got taken away which I really thank my Mum for. A lot of people did get taken and horrible things happened to them. I was one of the lucky ones, actually, and that's how I see it. And that's what I say to my kids - Mum had it hard, we've got it easy these days but we've still got to know about our culture.

I pass it all on to my daughter and the younger boys there, trying to get them to understand culture because they're brought up in a white man's way. Living in Melbourne, for us to go back home to Country, it's pretty hard if you haven't been there for a while. We never got taught cultural stuff when we were young. Nan used to speak her tongue and when we used to try and speak it she'd give us a clip. ‘Don't speak that, the white man will come take you away.’ So we didn't start learning our culture until we were in our late twenties. Our younger kids are learning it now. Ladjis, the lost tribe, wasn't lost, we just moved away for work!

Getting to know your culture, where you come from, what your totem is, was an eye-opener for me. Twenty years ago I didn't know nothing hardly about my clan group. I knew a lot about Aboriginal stuff but not your own, where you come from, because a lot of people wasn't talking back then. Information doesn't get passed on and it's a shame that it stopped.

I'd never seen a photo of my grandmother, my great-grandmother Katherine at Ebenezer, and it's good to see some faces and make that connection. I always thought we were just from Mildura. You find out your connection once you get into land justice. I've been involved with the Victorian Traditional Owners Land Justice Group for seven years now. I just stepped down as co-chair, give someone else a go at it. But Land Justice has taught me a lot about legislation and policy writing and a lot of government red tape that we have to go through to achieve land justice because we can't claim for Native Title. Hopefully we'll get our Traditional Owners Settlement Act through. So we have to negotiate with the government to change legislation so that we can have partnerships instead of the state holding everything. Lobbying the government has been very rewarding for me. Pushing me and it makes me a bit stronger standing up for our rights.

Yulendj is very exciting. It's a voice for our culture. It's another way of showing that we weren't the race that we'd been portrayed to be. This is how we lived, and our system lasted for so many years and that's good that the museum's going to portray that.

Sharing's been amazing, sitting around with Elders you learn more. I find the knowledge around the table is very valuable. I take in everything. I feel like being the sponge at the moment. You just absorb everything and hopefully I can use it when I'm that age. Getting it out now with the kids and that. Hopefully this will educate people and make them understand you've got to look after the land for the land to look after you.

There's this feeling that comes over you. It's happy and it's sad all in one. It's like you're happy you're seeing sacred things and you feel sad that they're locked away and people can't see them, but then they're locked away for a reason, so we can have them forever.

Showing our culture will enrich everyone’s culture.

I was born at Robinvale. We don’t identify the towns as our place on Country, so I was born on Tati Tati Country. We’re part of the Tati Tati, Wadi Wadi and Mutti Mutti tribal lands and language group.

I don’t class myself as an activist but we’ve been protesting at mine sites and large construction sites and projects that are impacting our water and our heritage and our land. We’re uncompromising in how we assert who we are and our rights.

The mining company offered us money to mine our land. We said no, we don’t want your money. We want the sites to stay as they are. Our land is our inheritance as Traditional Owners. No amount of money can match up to the benefit and enjoyment we get out of just seeing our land in good condition. What we’re doing is for our kids, so we make sure we involve them.

I suppose a lot of people don’t realise that the decisions they’re making today, they’re not thinking about the kids’ and the grandkids’ rights in the future. They think that they’re doing the right thing now, but in the bigger picture it’s actually eroding and extinguishing our own rights and our children’s rights. We want our kids in museums and government departments. We want to educate them, but also they’ll have that fighting instinct in them that they learnt from us, that was passed down from our Elders too.

Yulendj is pretty special group of people, Traditional Owners, with a lot of knowledge and understanding of who they are as individuals and who we are as a group. I’m getting as much out of being a part of Yulendj as what I’m bringing. There’s a strong relationship now, and that’s based on museum staff showing respect to Yulendj members, and Yulendj members imparting knowledge back to museum staff here. I think it’s unique. It’s setting a new standard.

I think non-Indigenous people have got an idea, a view, a stereotype, so my first hope is that this exhibition will enhance their understanding and how they see Aboriginal people today and in the past, and will influence how they will see Aboriginal people in the future as well. So as an educational tool, you can’t quantify how important it is. That won’t be seen for years to come. I hope it enriches their life too. I think it will. Showing our culture will enrich everyone’s culture. What I hope our people get out of it, is the understanding that no, our culture is not a past culture. And they’ll get pride and strength out of it.

To be in the presence of these objects which are spiritual and sacred to the makers, the deceased Ancestors, you feel a responsibility because not a lot of people actually got to see these things. It makes you feel a responsibility to make sure that the descendants out there get access to these objects. Without access that’s a ceasing of that aspect of cultural life and history.

We still use our traditional words as well as English. We might not have been using all the words, but we’ve been using our way of expressing and communicating with each other, that’s our language as well. We’re the flesh and blood of our Ancestors. We might be a bit fairer, might have different shape, but how we communicate is still in that way as well, except we’re using an English dialect. In that sense, we’ve still got the skeleton, we’ve just got to put the meat back on the bones. We’ve still got the framework of our language still intact. As long as one person’s still speaking, then the language’s not lost. My cousin, my kids, my partner and our family group are writing songs in language, recreating songs and stories.

I’ve been involved here in the museum, four or five years now, looking at the collections. I came along one time unannounced and one of the workers couldn’t take me in, they were busy or something. So when I went back home to Robinvale I started making objects. My kids, they’re never going to need to go to the museum to see their objects, they’ll be right here. I don’t want my kids or grandkids ever have to need to travel 500 kilometres, unlocking a door, unpacking a box, to see their peoples’ objects. Over the past few years I probably made a couple hundred objects, just heaps of things. Cutting canoes, shields, boomerangs, clap sticks, throwing sticks called woomeras or nyuks, bowls and bark paintings. I’ve done about 20 paintings this year and I want to see that art travel. I want to see it become a force in itself.

...do you realise, when you’re dancing, what you’re doing on this Country is what our family was doing thousands of years ago?

I am a Wurundjeri Elder and I identify with the Ganun Willam Balak clan. I was born in Carlton. 12 months out of my life I lived in Canberra. But the rest of my life I’ve lived on Country. Growing up, I always associated with Maroondah Dam. My family and I visit there a lot. I still remember what it was like before now and how the water was flowing, the creeks were flowing, beautiful countryside you could walk though. That’s still my favourite place in my heart and I love going there.

Working on Country makes me feel connected to my mother and grandmother. My welcome is always done in their honour. That’s why I wear my possum skin, because that’s my mother’s name - Walert, possum.

Last time I was with the Jindi Worabak dancers, they did a dance after I did the welcome and I stayed on stage with them. It was an emotional day and I was really teary. When we went downstairs to the dressing room I said, can you all gather around, I need to speak to you. I said how proud I was of them. I said, do you realise, when you’re dancing, what you’re doing on this Country is what our family was doing thousands of years ago. I’m always talking to kids or grandkids when I’m driving or going on Country, I’ll say there’s your river, or did you realise this about Uncle William Cooper and Great Uncle William Barak.

I’m just glad to be who I am. I’m a mum, I’m a stepmum, I’m a foster mum, I’m an aunty, I’m a grandmother. It feels a bit old being a great-great-aunty but I am. Being the head person in your family is very privileged. I have three of my own. A foster son and a cultural daughter makes five. Whoever needs to come stay with me, comes to stay with me, it just depends, because I’m an Elder in the Wurundjeri community as well as the Dandenong community. I’m the matriarch of the family so my responsibility has broadened.

At certain times in life you wonder why you are here and what it’s all about. I think with me, I have a special gift in healing so that’s my journey, because our community as a whole, not just Wurundjeri, are hurting. That’s what brings me close to my Country.

When I first was asked as a member of the Wurundjeri community to be on Yulendj, I really thought I didn’t have the knowledge. But I thought, yeah, I’ll come on and learn. It brings back memories that you haven’t remembered for a long time and I get very emotional being here, extremely emotional when I go home to family and tell them what I’ve seen and what we’ve been doing. I’m very excited and I feel very proud to be amongst some of the members of the committee who are very knowledgeable. They give the gift of their stories and I think it’s beautiful to hear all of that. I think it’s great to be acknowledged as a Traditional Owner of Melbourne by the group. Our smoking ceremonies are very special here. I look forward to coming. It brings me hope, brings me peace.

I’m hoping that people realise that yes, first peoples are still around and we still practise our laws and customs. Hoping that it will bring us some peace as well because we’ve been scattered around and had children stolen and a lot of horrible things through our history. I think having someplace where people can go to see a snippet of that history – and ourselves, even bring in our children and grandchildren – will help us heal.

Since we’ve been on this group, I’ve noticed that the attendance from the Koorie community has increased. You never went to the museum unless you wanted something – to look in the historical record or you needed some advice – we didn’t come in here, a lot of us, to just look. I think when the Koorie community come in and see how represented they are, and every mob’s being represented, it’s going to be awesome.

The best way to describe it is one of those patchwork quilts. Everybody's got a different story and them patches all join together.

My mob covers a very big area. Through my father's mother, it's Wuradjuri and through great-grandfather, the Yitta Yitta and Narre mob. Yorta Yorta is my mother's people and the Barrapparra Barrapparra and Wemba is my mother's father's area.

I was born in Balranald and raised on the mission to the age of about 14, 15. Growing up on the mission is probably one of the best experiences in my life. We lived in one of them tin corrugated iron huts that dad built. Some of the families had regular housing and a lot of the other families had tin huts scattered through the mallee there just down a little bit from where the mission houses were. Mostly our people were all workers and that's one of the things I'm proud of.

I'm number ten out of 13 kids. Nine boys and four girls. We pretty much had a free rein except that we had to do our chores before and after school. We walked to school, which is probably about five kilometres every morning and five back. Summertime it was good because we'd walk along the river track and then we'd accidentally get fallen into the water or pushed in. That was the story that Mum got when we got home. If we fell in the water, we'd swim down with our clothes then we'd get out and walk. Then we'd rub dust on our legs and arms, make it look like we's all hot and bothered. I think Mum and Dad knew - you can't get anything over on your parents. In the wintertime we weren't allowed to catch the bus because it was a whitefella's bus only.

We'd go to Sunday school every Sunday. Mother was a Sunday school teacher. This other old lady, God bless her, Miss Aileen her name was, she used to come down on this little bike with a little basket on it. She used to bring down cordial and bag full of broken biscuits. She'd give us these broken biscuits and cordial for behaving in class.

We didn't know about Christmas. I think the first time was when that old Sunday school teacher and the policemen, they come along and the men built a bower shed near the church. Mum made a big Christmas cake and then the policemen took the boys out to the mallee and cut down this tree, the best-shaped like a Christmas tree. And I tell you, that's stretching it. Anyway, they put it up and we had to decorate it. We had crepe streamers hanging on there, we'd make little bells out of foil lids and then some of them we'd roll like balls and tie them onto the tree with different coloured cottons. And Santa Claus used to come down in the sergeant’s old VW bus, jump out, and us kids had it worked out. Ho ho ho, we'd be there, laughing, but we'd play the game.

My aunties and uncles, God love them, I reckon they're all gone now, they were all valuable. In the Aboriginal community everybody's valued and cared for, I'm happy to be a part of a community like that. The sad stories like our cousins that were taken away, that was very emotional, very traumatising and then you see uncle and aunty just fretting for their kids and they can't do nothing cause of welfare. They thought it was their right to go and break up families because they thought they knew better. I'm sure a lot of those people now would say what the hell was we thinking when we did that.

My auntie, God love her, she had her children taken off her and I don't know whether it was before or after this event. All the boys were at my auntie's house up this end of the mission and they had a horse there. They're all riding it and showing off what they could do with the horse. My aunty walked out, she grabbed her dress, tucked into her bloomers, got on that horse and she stood in the stirrups. She had one hand with the reins and other little bit of rein she's hitting the horse. She rode around there, brought it back. Then she took it to a standstill, slid to a halt and while it was still sliding she jumped off and said, see if you can top that. All the men they looked so dumb. She shamed them right up! Aunties used to shoot sometimes better than the blokes. Work hard, chop wood, good staunch women. Sometimes I just laugh at how good them women were. But that aunty there I could not believe my eyes.

I truly thank God for my mum. She was strong, staunch woman. I don't remember going hungry. There was times when it got pretty close but she always had a vegie garden, always had chooks. Dad and some of the men used to go out and kill wild food and bring ‘em back so wasn't really missing out on anything. I'd back up my mission life against any kid's life now and I know which one I'd take. All our Old People seemed to be happy and used to laugh and had a lot of resilience and never allowed the negative stuff to hold them down or hold them back. I would not swap my life for quids, even the hard bits, because if you don't have the hard bits, how can you appreciate the good bits?

My sister was first girl after seven boys. We've done some funny stuff together, like we've worked down here in Melbourne. What we used to do to find our way around Melbourne is we'd jump on the different trams and trains and say, we'll go to the end and come back, then we'll go there and come back. We had a good time, I tell ya. We all worked. Everybody used to be over here at Fitzroy. And then we both worked out at Swinburne and then we come to town, blokes whistling at us, sometimes we'd whistle at the blokes on the tram. Born stirrers, I tell you.

The emu egg was my father's trade that he learned off his uncle. They'd carve with a pocket knife and a little three-quarter file. Sometimes when they didn't have a pocket knife they'd carve with glass or sharpen a jam tin. His uncle Joe Walsh, he was a beautiful carver. Both of them two old fellas, as far as I'm concerned they're the top artists.

When I started carving is when my father passed away. None of the boys took it up so I took it up. So I carved a couple of eggs, because dad had some eggs that people had paid for and he didn't deliver the eggs so I finished the eggs. I was basically doing it for my father's sake, keep my father's name going in the art world. And then it changed over to doing it for myself and my children. My carving knife is like a scalpel. I use two different files, an eight inch file and a six inch file. There's about 13 to 15 different shades in the egg from the outer layer down to the white. The white one is about the thickness of two cigarette papers. When you've finished, you wrap it up and put it away and don't touch it til you sell it.

I had an exhibition and they said what are you going to name your exhibition? I said, call it ‘Mission Breed’. I've since designed this jacket and it's got Mission Breed written on the back of it. Everyone try to make you feel shame that you were mission breed. The whitefellas used to say it to us. I'm not going to let this happen. I'm proud of that and I'm proud for the fact that most of our Old People all worked hard, I'm proud for the fact that all our top workers in Melbourne and Sydney and Adelaide have got good jobs.

Things happen for a reason and I feel very privileged that I was asked to be a part of Yulendj. I get a lot of pleasure out of it because of our history, and it's just great to meet everybody else that's around that comes as well. I feel like you're walking in to another family. The best way to describe it is one of those patchwork quilts. Everybody's got a different story and them patches all join together so that you've got that overall story. I really appreciate the time that I have when I come down here. I've really enjoyed meeting all the museum staff as well. Cause then you're starting to build up new relationships, new friendships and it just adds to the storyline further down the track. Each person, everyone's got a story, everybody, not just Aboriginal people.

We try and live our culture daily in this urban environment, but we try to get up on Country often to have that reconnection and rejuvenate ourselves.

My mob is the Jaara mob, also known as the Dja Dja Wurrung language group from Central Victoria. Our lands go from Boort in the north over to Rochester, down to the slopes of Mount Macedon in the south and over towards Ballarat in the west. I was born and bred on Country. Most of my kids have been born and bred on Country.

Dad is very highly respected Elder in the Jaara community and Country and in the wider communities. Dad's built a lot of relationships with community and government organisations. He worked for Parks Victoria for just on twenty years and so that's kind of set the foundation for a lot of the relationships in Bendigo and surrounding districts.

It wasn’t until I had kids myself that I really understood and cherished the value of cultural knowledge. I'm Dad's protégé so I follow Dad everywhere, everything he does, I'm with him. He started doing the same with my kids. Dad's so proud of his grandkids. He would take us on walks up to Mount Lanjanuc in Castlemaine, which is Mount Alexander, and certain times of year show plant foods and other sites. At the time, I had the two eldest boys who were probably seven and five. He came to this big rocky outcrop where you could get a really good look way over to Maldon and right out to Carisbrook. It was just on sunset and Dad was standing so you could get the silhouettes of everyone. He said to my youngest boy, come on now, it's time we go home, and this little fella held Dad's hand and said, but Papa, we are home. I was half teary, Dad was a bit teary, because it was just one of those beautiful moments. They know Jaara Country is home.

We try and live our culture daily in this urban environment, but we try to get up on Country often to have that reconnection and rejuvenate ourselves. I also get involved in local community up home. We have a place called the Keeping Place where we do workshops with local Aboriginal kids, and weaving and storytelling and that kind of stuff. I have a business doing events, but through that I've also started a youth project where I'm trying to use events industry knowledge to give Aboriginal and Islander kids opportunities to follow their dreams. I'm trying to create those opportunities for the kids to do stuff they'd not normally be able to do and to talk with high-profile people that they may look up to in sport or music. In today's society, Indigenous kids in particular face different barriers – they can push through that to try and achieve their highest goals. Like Dad always says, we're getting there. We will get there at some point.

I am so proud to be part of Yulendj. I honestly feel so blessed to have been asked to be part. This was something my Dad would have been involved in but he's unable, so I'm keeping Dad's place. I think it's so amazing to be surrounded by Elders and people with such knowledge from different mobs. Being the younger one of the group, and being able to be part of that and build something that's so big and representative of the whole Victorian nations, I'm honestly blessed. I love it.

As soon as my kids know that I'm coming in they say aw, can we come? Because they love it and it gives them connection as well. They get to see further back and see evidence, not just through their mother or grandfather telling stories of what used to be and what used to happen. It reassures them that that's their culture. They've had their grandfather and myself to always keep them grounded in their culture.

You get so filled with culture being here. It's like you get this burst of culture back in this setting, because you can lose your way a little bit living in the city. I believe that it gives you those prompts to do more, to go home and do more. It keeps me passing on more of those dances and songs and language. Being around those objects and seeing things that I know my people made with their very own hands, all the stuff that they've been through and our whole race has been through, and me here today, it's really overwhelming but at the same time rejuvenating. It peps me up to keep going and do more.

I really hope that visitors to First Peoples feel the very heart of our culture and our story. They'll walk away as if they've really experienced it with us, and then they'll want to know more. Local people and even Aboriginal people from different parts will really get how us Victorians were. We tend to get forgotten as Aboriginal people as opposed to the Central Desert or Kimberley region up north. So that's what my hopes are, that people really get a sense of who we are, and that we're a living culture. They get to walk away as though they have travelled our paths.

It's such a battle to try and break down the stereotypes of what an Aboriginal person is or should be or looks like. A lot of people didn't even think we were still here. I think that to say that we are is actually a big thing for us.

I feel I'm protected by the Ancestors and Biame and a lot of spirits.

I'm Yorta Yorta and Wemba Wemba. My grandmother come from Wemba Wemba. I was born in Mooroopna and lived on the riverbanks there. My father, when he filled in a form, and it said place of abode, he put 'riverbank, Mooroopna'. I'm really proud of that. We weren't allowed to live in town so the riverbank wasn't too bad.

We used to go up to Swan Hill picking grapes and whatever was going - tomatoes, peas. Mum used to make us all a little bucket out of the Sunshine milk tin and we had to pick peas. But I ate more than I put in the bucket. We used to set traps, we used to round up the sheep, take them to the shearing sheds. We used to go to school, I used to ride the bike ten miles in and ten miles out. That was my real happy times from when I was about eight to twelve.

I live right in the Barmah Forest on private property. I'm sort of a caretaker there and I live mostly on my own. Summertime I get a lot of visitors come out fishing and rowing the boat and learning. I thought I knew a lot of things about the bush but when you live there for a while you connect with all the little creatures and the birds and their calls. Even when I'm inside I'm still outside in my mind, listening. When I hear the cockatoos carrying on I think well, it’s the eagles. So I go out and there they are. The little firetails used to fly off but now they've got used to me and they don't fly off anymore. We got chooks out there too, they keep me company and I watch what they do. Funny things. So I'm not lonely. It's a great spot and I think people should connect more with Country and themselves.

A friend bought me a boat so I can cruise up and down the river but I get tired of all the other boats out there. Fools get on the river and no respect. You hear comments as they go past sometimes about Aboriginal people. I don't take notice of them. I'm not afraid. I feel I'm protected by the Ancestors and Biame and a lot of spirits. He's our spirit guide. I always talk to him out there. It just feels so good that I'm connected to him. I try to get some people out there, our mob, to come out but I don't know, you talk about spirit and stuff and a lot of our people don't understand that he's there.

When I first went out there I used to put blankets up on the windows so they can't see in. I don't do that anymore. It just took me a while to lose all that negative stuff. If there's any danger, I know that I'm protected because there's always a sign. I know when a snake is nearby because I can feel him. And the willy wagtail makes a certain sound when there’s one around. I hear them and then I go and check, and sure enough there’s a snake there!

Not a lot of kids want go bush now. Even my grandkids, so I've got to write things down if they don't come and see me. There's a Native American gathering concept about sacred fire so I did three of those on Yeilima in the forest where I live. Some of my mob came but there was a lot of healing with white people. They're learning stuff about us. Even though they were whitefellas, that doesn't matter to me anymore. There was about four of them doing Aboriginal studies at university. We can teach them things, even our own kids, to show them what happened here. A lot of them don't know.

I love doing art. I make fish out of boards and wire. My father was a sculptor and used to do kangaroos and emus, emu eggs. I like to try anything and everything. I do a lot in meetings. Annoys people sometimes because they think I'm not listening. You don't have to look at the person to listen, do you? I've got art at the Nathalia hospital, on glass there in the waiting room, and I've got one at the Austin Hospital in the cancer ward.

I got a Masters of Applied Science at Deakin University when I was 50 and I thought I was too old. I did it about the Dungahla (Murray) River and where we lived and how my mother respected everything. Little bit about the Murray Darling Basin, their story and my story. Six years and I was working with the Native Title Legal Service. I've been on the Cummeragunja Aboriginal Medical Service as the chairperson for sixteen years. I sit on the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council. I'm one of the directors for my region. When I was at Cummera I was the hairdresser, the vet, the doctor and just everything.

Caroline rang me and asked me to be on Yulendj. Good thing. I'm a bit shy and words don't come too easy for me. One on one I'm OK. Mob or not, I sort of sit back, listen. But happy to be here and contributing my life, growing up, hard times and stuff like that.

It was good to connect with the Yorta Yorta cloak. Those things, they had their own protection and spirit, handled by our Old People. I always think ‘my Ancestors had their hands on that’. I never touch them, even with gloves.

Don't lose your ground or your roots of who you are and what you are.

My rightful name is Diana but I've been called Titta since I was six weeks old. I was given that name by my auntie's cousin in South Australia, so it means more to me because it was given that way. My mob is Jardwadjali and Gunditjmara. Gunditjmara is from my grandmother and the other one's from my grandfather. I was raised in Horsham and most of my knowledge I got from my grandmother.

Nan was hard but fair. Mum was her last daughter so we were the last of the grandchildren. I was closest to my grandmother so she taught and showed me a lot. And that's from both sides, from the Wimmera area, plus down Western District where she grew up.

When my mum died six year ago I had a nervous breakdown so I pulled away from everyone. By coming to Yulendj and mixing with the small group of people it's bringing me out of my depression. It's one way of me healing as well. Meeting people from all across the board, it's making me feel good and you know where you sit. Everybody's put in and it's all joined and it's all connected like a river and it's still flowing through. Esther, her uncle married my grandmother. Eileen Harrison is my cousin on my grandfather's side. Eileen Alberts is a cousin on my grandmother's side. There's a bit of connection here there and everywhere. I learn from the other old Elders as well as I give them what I know in my area.

I'm excited to see that the stuff is still here and in good nick and it's there for me for generations to see. When they started to show us objects, Amanda was with me and Lisa and she opened this drawer and then there was the breastplate. It was from our area and I had my gloves on and I said to Amanda is it OK if I picked it up just to see what it felt like, I just want to see how heavy it is and see what it felt like around your neck. When I did that I seen the bloke's face that wore it, and I go ‘thank you and now I'm putting you back’.

They brought out the Wimmera necklace with the kangaroo teeth and the emu feather skirt and a shield. I was looking at the photo board and I took a photo of my grandfather, Captain Harrison the First. A couple of days after I went home and going through my photos of the objects that we've seen then I've looked at his photo and I've gone, oh my god, he's wearing them. Connecting pieces back excites me. I've always liked going back and doing research where people fit in dates and all that and this has made me want more. It's opening new doors for me to keep researching.

I found a few photos in there of cousins that have passed away. I found a photo of my mother before she was taken away, Stolen Generation. And that's where I found photos going right back, photos of the first Captain Harrison, my grandfather, and going back to find my grandmother's father. And getting those photos and keeping them not only for my records, for my grandkids, to say this was Nan's father, this is where we actually come from. Don't lose your ground or your roots of who you are and what you are.

I had children, three of them, two boys and a girl. I always said to them, if you didn't have a job you couldn't leave school and if you have a job, don't leave this one until you find something. Those were my main rules and when you left work at five o'clock, you leave work business, you come home and enjoy being with family at home. And that's still the same. I teach my kids in conversation. We might be watching TV and they'll just ask me. Or we're out driving somewhere and I show them. I've done that with my kids so I'll do it with my grandkids. It's the same way Nan taught us. One grandson he reckons that he's Bunjil's. The other one turn around and says that the old kangaroos are the old blackfellas coming back. I'm teaching them and they're bringing their knowledge, and they say they've been here before. I go with their little stories and we feed from each other.

I used to drive a 12-seater bus, pick up kids, take them to basketball. Come Friday night, basketball again, pick them all up, keep them out of trouble. Saturday take them to football then on a Sunday we'd go and do a Sunday trip for the footy. I'd be feeding these busloads of kids and I'd be the only parent on that bus. Those kids are all grown up now and they respect me as Aunty Titta. That's the thing I used to do for the community. Before any of that I raised my two brothers and my sister for my mum.

I was one of the first to work for the Community Justice Panel in Horsham. I set up a women's group and run the Werrimul Arts and Crafts workshop. I’ve taught women how to use sewing machines and overlockers and we started up a women's group at Goolum Goolum (Aboriginal organisation). I worked for Parks Victoria as the first female Aboriginal summer ranger. I don't like the word Indigenous, but anyway, the first Indigenous Summer Ranger across Victoria. When they put up boards or they talk about the Indigenous side of it, they always bring my photo up. I did the possum skin cloaks for the Commonwealth Games and I wrote myself a little book eleven years ago. I decided to put it out about 18 months ago now it's just going wildfire. I've had interviews all over Australia on radio and I've been to two book shows in Melbourne. It's not a story about AFL or VFL, it is a story about a possum skin football when it was first made and who it was made for. I wanted to write what I'd been told about possum skin balls for the kids of the area. I've been in and out of schools reading my book also doing culture talks for schools across the board.

I can't wait for this exhibition to open so we can go in and have a look and be excited first before anybody else. That's the bit that I'm waiting on, the end bit when it's all put together. I can say to my kids and my grandkids, I was a part of that, and be proud that I've done something for not only just for my family but for everybody back home. That there's part of them in there as well. We can say, this is what we've got. This is our showcase, come and see. We're not gone, we're here still so take a wander and have a look.

Hopefully visitors walk away with ‘I didn't know that’ or’ wow, that was good’. I worked for Brambuk where the public's coming in. Being light-skinned, that was the only problem I had. They expected to see real blackfellas and you're trying to explain to them Victoria don't have that. Where we are now, we're getting that across to the public and without them even knowing that they've been told, they can see for themselves.

Language is land, land is Country, Country is you.

I’m Yorta Yorta on my father’s side, Ngarrindjeri on my mother’s side, but I’m supposed to have connections through my great-great-great-grandfather within Wathaurong Country (Bacchus Marsh). I grew up between Swan Hill, Geelong and Deniliquin.

When we moved back to Swan Hill I started to learn about who I was. It’s not that Mum wasn’t telling me, it’s just that I didn’t ask her the questions. It wasn’t until she was introducing me to other family members, was when she started to talk as well. But it was the uncles who taught me a lot about who I am and a lot of my cultural information. A lot of the local mob down there don’t know the history, and they’re relying on me to teach them. One of the uncles, if you didn’t do it right, would slap you round the ears. “That’s to remind you, boy, that could have been a snake biting you.” Yes Uncle, I understand now.

I’ve learned a lot about Geelong through older people, not necessarily Aboriginal people, ninety year old plus, who’d had contact with Aboriginal peoples around the area. So I got to know a lot about that Country down there, where things are, and how and why. I’ve learnt this and learnt that, because I’ve made it my business. When you’re in a person’s Country, so you’ve got to respect that Country and know as much about that Country that you’re living in as possible so you can look after it. So that’s what I’ve done all my life. Between Geelong, Swan Hill, Kerang… I worked in Bendigo, got to know about that Country from that local mob there. Kerang, which is actually part of my own history, got to know about that place. It all connects.

I think other organisations around Australia and around the world should take a leaf out of this Yulendj book. If they’re going to talk about traditional peoples of their countries, it’d be good to have the traditional people involved. A lot of us aren’t traditional people – we’re custodians of the knowledge that’s left. And it’s up to us to continue those stories.

Since the late seventies, early 80s I’ve been coming to the museum. They showed us these spears, 200-year-old spears. To be able to touch them – obviously with gloves – wow. The wood’s turned to dust but if you look at the spearhead and the sinew it’s all still perfect as the first day it was put on. Why? How come? Being able to look at some of this old stuff reinforces the intelligence of our Old People and how they made the spears and made them to last.

I’ve been involved in language all my life. When I became a Koorie educator we were looking at Wiradjuri language and then we come across Wemba Wemba language stuff and then we started incorporating local language into schools. It’s brilliant stuff. We all know that language deals with Country and this is what I’m doing, trying to explain to people, if you want to know your Country, you want to learn your language. Language is land, land is Country, Country is you.

Museums Victoria would like to acknowledge the passing of David Tournier and pay respect to his family and community. David was an important part of the Yulendj group and his contributions will be forever present.

Along the way people told me some beautiful things. Yulendj gives a chance for their stories to be told.

I’m of the Taunwurrung people but I was born up at Mooroopna. In 1956, I was rounded up from Daish’s Paddocks, along with a lot of other people, and taken and put into an orphanage. I would have been not long past my second birthday. As I turned five they moved me into a boys’ home in Box Hill run by the Salvation Army. I knew I had a sister but that’s all we had, just us. She got fostered at five, but we somehow were able to keep in touch.

From there I was fostered a few times till at eight I was fostered by an older couple. In the eyes of the police in them days, someone marked as a ward of the state meant that they were a troublemaker. At the age of 10 or 11 the police pulled up and threw me in the divvy van and dragged me to the police station, because I had a file, which I didn't know I had. From then on we had an ongoing misunderstanding. I reckoned they were beating me up for nothing so I started to do things.

I was 14 in Turana and the referendum had happened. I was in doing a little bit of time for just minor trouble and I joked with them, ‘hey, I'm a citizen now, does that mean you can let me out of here because I'm no longer a ward of the state?’ A few days later they passed me a letter that had been written in 1965. It was by a baby brother of mine, telling me about his mother's birthday. They all tried to have a party for her and instead she broke down and started crying. The letter said then, she told us about you and how you'd been taken. He informed me that he was my brother and there was another sister and another three brothers, and enclosed was a photograph of them and mum and their address.

So I went and visited. Under the state government rules at the time I had to go with my foster parents. My mother was a bit wary. Next time I went by myself and she was trying to tell me about the other brothers and sisters who'd been taken.

I got to be about 16, 17, and I had a pretty good probation officer. I was telling him I thought I had extra brothers and sisters and nobody seemed to know where they were. He asked me if I wanted a cup of tea while he opened my file. I said yes. I had an idea he was up to something. He left my file open and left the room. I had a look and there was my sister's address and the foster parents she was living with. I met her on the quiet and gradually we let her know that I was actually her brother. There was another brother but unfortunately it's taken till this year to find him. In the meantime, all the other aunties and uncles were telling me about their sons and daughters missing and some of them I knew from the orphanages. I didn't know back then that they were relatives.

One day I went to the pub with a couple of older cousins and they got into trouble and their mum was telling them off. I'm thinking, I'm sweet, I'm safe, and then she started blasting me - as their Elder I should have known better. So I realised then that I was supposed to have a leadership role in the family.

I started fruit and vegie picking. A lot of Aboriginal people in them days were fruit and vegie picking. I was a young fella and they'd tell stories of the old days because they'd always go Walsh, eh? Who's Poppa Joe? Oh, that's my grandfather. He and Nanny Effie were looked at fondly and people would tell me stories about them.

My first outreach job with the Legal Service was going down to the Fitzroy Parkies. Half of them were from orphanages too. I started helping the boys. I'd go talk to the Aboriginal Housing Board, they’d tell me what restrictions they had or how I could bend the rules. Some of them had drug problems, alcohol, that was getting them into trouble. Over the years I've maintained friendships with them all. Every time I go down the park, the head Parkies always introduce me the new ones and say, this is Uncle Larry. They accepted me as the Uncle Grumpy and the Elder.

They were then starting to form groups like Aboriginal Community Elders. Because I'd been helping some of the homeless Aboriginals with their housing, they called me onto that... it's how I actually met Aunty Iris Lovett-Gardiner. Aunty Iris would yarn with me because she liked the way I did things. She talked to me about some of my rellies and how they as old people, because they weren't living with their family, no one was looking after them and they died alone. And she's gone, we're looking to get a place, an Aboriginal Elders' Hostel where they can stay. I helped organise for her to meet several ministers and on the way she'd yarn to me about the old days. I did OK at maths and more than OK at English, but I was always getting 90s for History at school. It was always one of my favourite subjects. So Aunty Iris is yarning to me about history and Uncle Stewart Murray is yarning to me and I'm listening and soaking it in. I helped them and so ACES (Aboriginal Community Elders Services) was built.

In Moe / Morwell they were getting worried about the arrest rates. Some of the people who were getting arrested were dying because they were old, ill, and the police were picking them up because they were drunk. Even though I was no longer working for the Aboriginal Legal Service everybody would phone me. Next thing I know I'm on the state committee and national committee for Deaths in Custody. I'd started out just by myself helping get my family back together then other cousins back and it all seemed to lead to the same problem. All these people, some of them I knew, dying in jails and they're all coming from orphanage and foster home backgrounds.

When a few of us decided we had to do something about the Stolen Generations, we approached Lowitja O'Donoghue. She agreed to put it as an ATSIC issue, I think reluctantly, because she had a good foster home but she understood us who had it good have to look after the ones that didn't. We went public. We got the papers in and we've gone look we're sick of this. And we told a little bit of our story and we pushed. The minister took it to Paul Keating, Paul Keating agreed there needed to be an inquiry.

Every one of the investigators came and met me. By the time the inquiry was up, I'd been all around Victoria talking to everyone going. You've got to go. I went to every inquiry in Victoria. I felt my responsibility was to go and encourage. I'd see someone that'd just been in the inquiry start to look like they were about to crack up and I'd sit with them. I just keep my eye on everyone. I finally went in as a witness and the funny thing was that I never spoke about me. I spoke about two of my best mates who both took their own lives. I talked about their lives rather than my own because they were the ones who couldn't speak for themselves.

I don't think my work's finished and I don't think that it's just about the Sorry Day, the Stolen Generations, the deaths in custody, the fights I had with police over rights, it was also along the way people told me some beautiful things. Yulendj gives a chance for their stories to be told. Uncle Stewart would drag me to a few meetings and he'd just ask me to listen to a couple and tell him afterwards what I thought and then finally going, you talk to them. Aunty Iris taking me to meetings and saying I want my nephew here to speak! They were good people who did a lot of things themselves and they gave me a chance. I had a reputation, in and out of orphanages and youth training centres and prison, a very tough character. And here's all these old men and women, they're the ones who built everything, going oh yeah, but we see him, he's a nice person really. For me, Yulendj is about letting people know about good people who helped get things going. We all know them by name or reputation but the stories aren't there.

And that's what Yulendj is about, getting stories out about people like that.