Many Nations objects

Many Nations contains nearly 500 objects from across Australia, showcasing the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.

The cases are displayed in six sections: Animal Creations, Marking Identity, Working Country, Celebrating Culture, Keeping Places and Toy Stories.

Eagle

Date 2013

Maker Mick Harding

Clan/Language Group Taungurung

Location Victoria

Materials Blackwood

Story

'Bunjil nugal-u gugra duworra-bun-iyt nugal-nganjin-dha gaaguk ngun godjin nugal-nganjin liwik ba nugal-nganjin garrimiin ba nugal-nganjin bunbunarik nerdu.

Bunjil is wearing a possum skin cloak as a mark of respect to him, while also acknowledging our ancestors, us today, and our children in the future.

The making of the Bunjil sculpture was a new challenge for me, using large and small carving chisels in combination with my burning skills to represent Bunjil in a respectful manner.

To make him look like a bird and wrap him with a possum skin cloak was to demonstrate that he is the creator according to us, the Kulin Nation, and how he gave us the rules to live our lives by. Wrapping him with a Gugra (possum skin cloak) was to show everyone that our ongoing use of the Gugra is a demonstration of connection to our country and culture, while the symbology of each of the panels of the Gugra and the unique mark making, belongs to us, here in the south east of Australia.'

Mick Harding, 2013

Date 1990s

Maker Not recorded

Clan/Language Group Amangu

Location Geraldton, Western Australia

Materials Mulga wood

Story

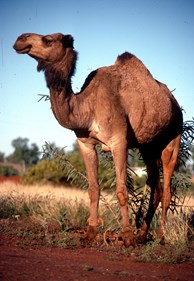

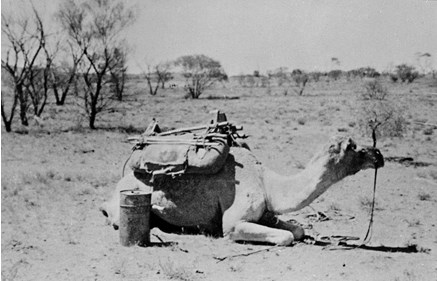

Between 1880 and 1907 up to 20,000 camels were introduced into Australia. In 2012, the wild population was estimated to be close to 1 million. Feral camels inhabit approximately 40 per cent of the Australian mainland. Around half the camel population is thought to occur in Western Australia, which is home to the largest herd of feral camels in the world. Around half the camel population is thought to occur in Western Australia, which is home to the largest herd of feral camels in the world.

Camels cause enormous damage to Aboriginal ceremonial grounds and other cultural sites, particularly those associated with water. The areas surrounding wells and rock holes are damaged and valuable supplies of drinking water are contaminated. The camels are causing changes to patterns of customary use and care of country, affecting people's ability to camp, hunt and to collect food and water.

Aboriginal traditional owners of the vast areas affected are key partners in the Australian Government's National Feral Camel Plan developed to manage the growing problem. Senior Martu owner Butler Landy says of the camels: 'I understand camels not belonging to Australia. They are a good animal but too many is too many, and it's hard to control and they move all over the place. It upsets me and sometimes it make me sorry to do what we're planning to do, but it is getting out of hand now these days. They're breeding more than the dogs I think'.

Ms Rosemary Wrench

Murray Cod

Date 2012

Maker Treahna Hamm

Clan/Language Group Yorta Yorta

Location Yarrawonga, Victoria

Region Riverine

Materials chicken wire, nylon rope, twine, wood, paper, gum nuts, plastic bags, golf ball

Story

'To Aboriginal people, the Murray Cod is called 'old man of the river', as this species of fish has been known to live to be the length of a man (6ft) [1.8 metres] and to weigh around 250lb [113 kilograms].

The Murray Cod's environment of Dhungala [Murray River] has been highlighted in the past several decades as being in declining health. In my lifetime I have experienced this. The water of the River used to be so clear that you could look down and see the trails, tracks and holes of insects and small creatures along the bank; now it is murky.

The fish sculpture represents the decay of the River, with the use of wire and pollution found and incorporated into its body. The golf balls are swallowed by the Cod, which they mistake for fish eggs, an interruption of their natural diet and also life threatening.

On the side of the sculpture, a membrane which is found within the body of the Murray Cod is highlighted. The membrane is said to be an imprint of the trees the fish was born under. Like eels and salmon, the Cod's life journey starts here and ends when the fish returns to die under it.

There has been an incredible impact on the River in the past. Dhungala is the creation site of the Yorta Yorta people and one that needs to be respected the same as any church, temple, mosque or other place of worship. We must always remember that a church can be rebuilt at any time and in any place, Dhungala cannot. We all need to remember, too, that we should not pollute any creation site as we would not a church.' Treahna Hamm, 2013

Ms Rosemary Wrench

Feral cat

Date 1989

Maker Not recorded

Clan/Language Group Ngaanyatjarra

Location Warburton, Western Australia

Materials Sandalwood

Story

'Rabbita - he only come to this country little while. Puppy-dog - wild dog - been here all the time. Horse and cattle come before rabbita. Pussy-cat he come long, long time ago - before sheep an' bullocky an' camel. My people tell me pussy-cat he come that way' [nodding to the west]. Long time ago, before white people come, big boat come that way and pussy-cat jump off, run about, find 'nother pussy-cat, and now big mob pussy-cat everywhere, run about desert country alla time; eat little birds, lizard, eat close up everything.' Pitjantjatjara man, Uluru, 1947

Oral history records the ngaya (feral cat) present in Central Australia for a much longer period than any other introduced animal, entering the desert from the west, possibly brought ashore by whalers or shipwreck survivors on the west coast of Australia during the 17th century. By the 1880s, ngaya had spread over the west coast of South Australia, from Port Lincoln to Eucla, the eastern most locality in Western Australia.

In Central Australia, ngaya were once considered to be mamu (a harmful spirit), with people becoming very sick and even dying as a result of a ngaya scratch or bite. Today, they are seen as a pest, flourishing as a result of the prevalence of rabbita (rabbits) in the Central Australia desert.

Ms Rosemary Wrench

Digging dish

Date 1957

Maker Not recorded

Clan/Language Group Pintupi

Location Western Desert, Western Australia

Materials metal

Story

For the Pintupi, on their country in the Western Desert, digging implements and carrying dishes are important in food gathering and for the maintenance of vital water wells and 'soakages'.

The Pintupi use a range of skills to exploit the resources available to them, and they incorporate new materials and influences into their cultural practices. The metal piti (digging dish) has been made in the same shape as the traditional wooden ones reflecting the significance and usefulness of both the design and tool.

At a soakage, the piti is used to scoop out the sand or mud, often to a depth of several metres, so clean water can be gathered at the base. Wells were covered to keep them free from fouling by animals, with vegetation used to block them. When a well fell into disrepair the people would bail the well, using the piti to throw slush against the wall. This would set like cement wash and help hold loose sand, preventing it from falling into the water.

The Pintupi and other Anangu (people from the Central and Western Deserts) transform pieces of sheet metal, car hubcaps, lids from metal food containers and the bases of metal drums into containers and digging implements. Women and men use these to dig in soft sand for yams and honey ants and to open up the burrows of lizards and small marsupials.

Ms Rosemary Wrench

Rabbit

Date 1990

Maker Mrs B.

Clan/Language Group Ngatatjara

Location Blackstone, Western Australia

Materials wood

Story

The rapita or pinytjatanpa (rabbit) first appeared in the Lake Eyre region of South Australia in 1886, from where they moved via river catchments such as the Finke into the Musgrave and adjacent desert mountain ranges. From there they spread quickly throughout the centre of Australia; by 1894, they had reached Eucla, the eastern-most locality in Western Australia.

The arrival of rapita proved devastating to local flora and fauna. They dug up and ate plant roots and consumed many ground cover plants, causing the extinction of several local animal species, such as the Wintaru (Golden Bandicoot), which disappeared after the spread of rapita from the east.

Ngatatjara elders today remember that when they were young they would eat Mitika (Burrowing Bettong), Malu (Red Kangaroo), ngaya (feral cat), Wintaru and Aala (Rufous Hare-wallaby), along with different types of mai (non-meat food). But after these animals were displaced, the Ngatatjara relied increasingly on rapita, which is an important food source today.

Ms Rosemary Wrench