Objects and Themes

The objects in the Securing Food Futures learning kit connect to three main themes that delve into the past, present, and future of food security.

Is the past the future of food security? This kit is designed to help us understand changes overtime in agriculture and food security.

This kit and teaching guide will allow students to practice geographical and historical skills as well as touch on cross curricula ideas from economics, civics, science, and visual arts. Using historical artefacts and events to build a foundation, students are encouraged to brainstorm and analyse ways of preparing for and predicting future outcomes of food security.

1. Investigating the past

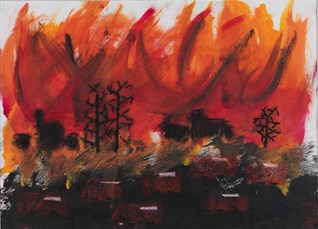

Historically, the narrative created by colonial settlers to Australia was that First Peoples were largely hunter/gathers, however, more recent discussions, evidence, and stories have brought to light the structured and seasonal agricultural practices of First Peoples communities. The use of cultural burning and use of sustainable and seasonal crop species meant that Indigenous communities were food secure and able to support populations for over 65,000 years.

2. Observing the present

Often when we consider food security, our first thought is linked with agriculture and farming. In Australia, land cover has significantly changed over time, from native bush and grasslands to largely cleared agricultural fields and urbanised spaces. Australia produces more food than our population can consume with around 2/3 of food produced per year in Australia being exported. However, while Australia is often described as ‘food secure’, around 4% of people in Victoria run out of food and are unable to afford to buy more.

Rates of food insecurity are much higher in vulnerable population groups, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (19%), lone-parent households (13%), the unemployed (12%) and people in households with an income of less than $40,000 (10%). Our relance on transporting food from different regions around the country or internationally (to meet the demands of accessing seasonal food year round) makes us vulnerable to sudden changes (e.g. extreme weather events like bushfires or health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic).

Modern food systems have a large impact on the environment. Monoculture (the farming of a single crop species) can result in biodiversity loss and other intensive processes can lead to dramatic shifts in land use, increased risks of water scarcity and soil degradation. In 2017, Victorian agriculture contributed 14% of net emissions – the fourth largest share of total emissions behind electricity generation, transport and direct combustion. This is driven by our industrialised way of doing agriculture in the 21st century, which is centred on large-scale intensive production of crops and animals.

References:

- VEIL (2016) Melbourne’s Food Future: Planning a Resilient City Foodbowl

- VicHealth (2020) Life & Health Reimagined: Good Food For All

- Export - Department of Agriculture

- Victorian Greenhouse Gas Emissions Report 2019 (climatechange.vic.gov.au)

3. Preparing for the future

As the human population increases and the climate becomes more unpredictable, it is more important than ever to have a reliable source of good, nutritious food that is culturally appropriate for all communities. The ongoing impacts of drought, flood and fire in Australia, as well as the recent COVID-19 pandemic has shown how vulnerable regions are to sudden changes and the impacts these changes have on consumers. Increasing global temperatures means that agricultural productivity is being impacted (e.g. reduced yields) and this is not only having an impact on food availability but also supermarket prices.

Globally, there has been an increasing focus on the need to create healthy, equitable and sustainable food systems as a way of building future resilience to shocks and stresses and to reduce environmental impact. There is a strong need to produce food in a way that conserves and restores soil and water ecosystems, promotes biodiversity, and builds climate resilience. While an increasing number of farmers taking this approach more still needs to be done.

One key suggestion is shifting a focus from rural intensive farming to urban farms and community gardens, reducing food waste and using precision farm technology. Further, there is increasing evidence that looking back to historical agricultural practices and crops used by First Nations peoples could provide a guide to more success and adaptable future agricultural practices.

References:

- HLPE (2020) Food Security and Nutrition: Building a Global Narrative Towards 2030

- Department of Agriculture (2019) Food Chain Resilience

- VEIL (2016) Melbourne’s Food Future: Planning a Resilient City Foodbowl